It was January, 1945 and Master Sgt. Roddie Edmonds had a gun to his head.

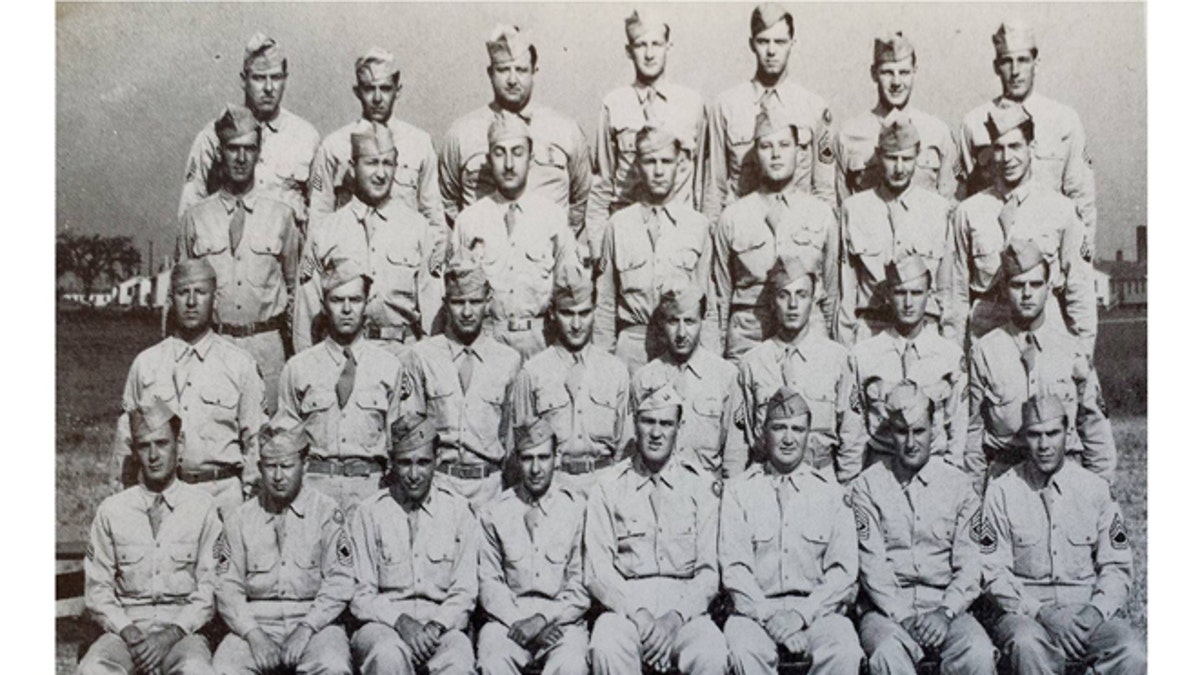

The commandant of the Stalag IXA POW Camp near Ziegenhain, Germany, ordered Edmonds, of the 422nd Infantry Regiment, to turn over the Jewish-American soldiers under his command. Edmonds and his men – Jews and non-Jews alike – stood together in formation.

"They cannot all be Jews," the German said, looking over the more than 1,000 POWs.

"We are all Jews," Edmonds responded.

"I will shoot you," the commandant warned.

"He was very calm, even with a gun to his head. It’s amazing even to this day."

But Edmonds had his own warning: "According to the Geneva Convention, we only have to give our name, rank and serial number. If you shoot me, you will have to shoot all of us, and after the war you will be tried for war crimes."

The commandant stood down.

Those four words uttered by Edmonds echo 70 years later, as a testament to the solidarity he and his men showed to their Jewish brothers in arms. And because of that, Edmonds’ name will be etched in history when he becomes the first American soldier to receive the Yad Vashem Holocaust and Research Center’s Righteous Among the Nations recognition and medal.

Only four other American civilians have received the honor – Israel’s highest for non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during World War II.

Edmonds saved an estimated 200 Jewish soldiers, whose chances of survival if turned over to the Nazis were slim. Although Edmonds, who lived in Knoxville, Tenn., died in 1985, his son, the Rev. Chris Edmonds, has a good idea of what his father would say about the honor.

"I think he would say they’re making a big deal about something he was supposed to do," Chris Edmonds said. "He fulfilled his responsibilities."

Chris Edmonds will accept the Righteous Among the Nations medal on his father’s behalf during a ceremony early next year. His father's name will also be inscribed among 26,000 others on the walls of honor in the Garden of the Righteous at Yad Vashem – a sprawling 50-acre campus of winding paths set amongst the Jerusalem pines of Mount Herzl.

"He’ll join some incredible people," Chris Edmonds said, as he looked at the rows of names as we walked together.

Among them: Varian Fry, an American journalist who helped more than 2,000 Jewish refugees escape Nazi Germany, and perhaps the most famous, Oskar Schindler, the German industrialist who helped save more than a thousand Jews and whose story was documented in Steven Spielberg’s 1993 film “Schindler’s List.”

Irena Steinfeldt, director of the Righteous Among the Nations department at Yad Vashem, said Master Sgt. Edmonds’ story is special because not only did he save his fellow countrymen, but he did it so late in the war when they were just trying to survive.

"Roddie Edmonds decides he’s going to take a terrible risk and maybe never return home because he believes in his duty to stand up for his fellow prisoners of war," Steinfeldt said.

Lester Tanner and Paul Stern were two of the Jewish POWs Edmonds protected, and recall how they stood next to him during the tense exchange with the German commandant.

"It was 70 years ago, but I remember it like it was yesterday," Stern, 91, said from his home in Reston, Va. "He was very calm, even with a gun to his head. It’s amazing even to this day. We never talked about it until now."

Lester Tanner, who lives in New York City, agrees.

"He was a true friend to his troops, a respected commander and one whom all of us followed those dark days in early 1945 with confidence in him," he said.

Chris Edmonds, who leads a Baptist congregation in Maryville, Tenn., has also submitted his father’s name for the Congressional Medal of Honor.

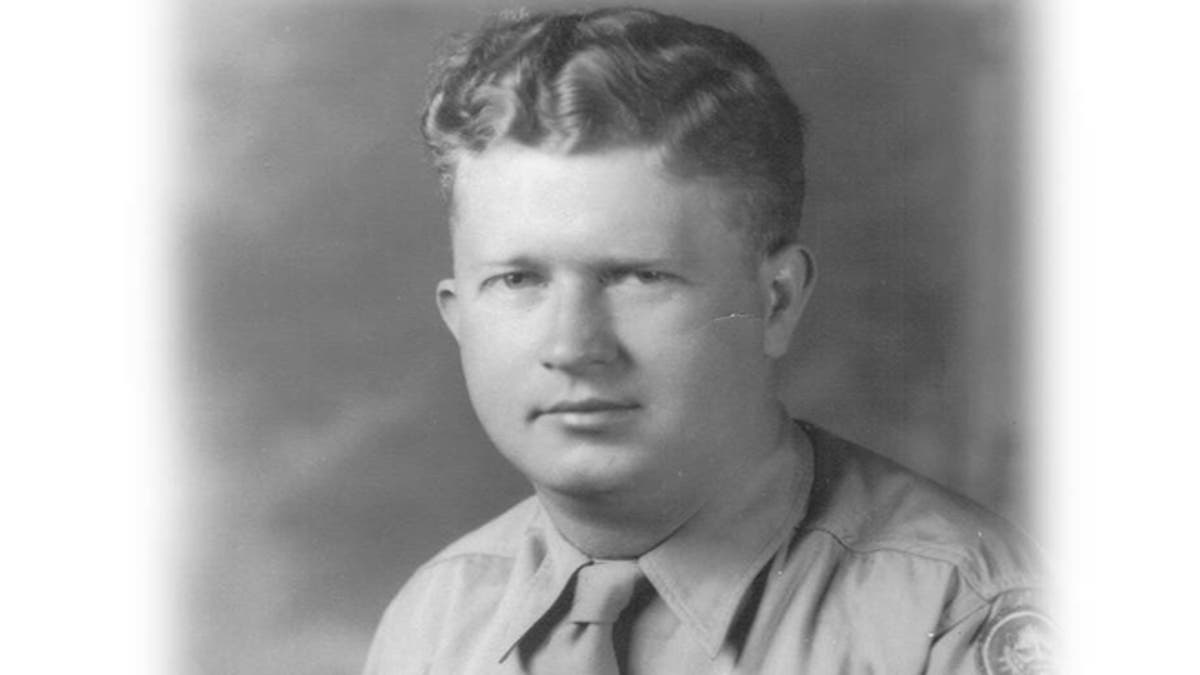

"He was just an ordinary man but lived in a way that was extraordinary," Edmonds said, smiling as he looked down at his father’s picture – a young Roddie Edmonds with a hint of a smile on his face.

"I never knew he had a [superhero's] cape in his closet. But he did."

John Huddy is a Jerusalem based correspondent for the Fox News Channel.