Putting Turkey coup attempt into historical context

Bryan Llenas discusses previous coup attempts and the role of the Turkish military

Last week’s failed coup attempt left Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan in such a strong position that many Turks and others believe he himself engineered it – or at the very least knew of it and let it play out to his advantage.

Supporters of the “staged coup” theory say there’s plenty of circumstantial evidence to support their claim, and have busily discussed and debated the topic in social media – which has a huge engagement rate in Turkey – and other platforms.

Among the questions being asked are why coup plotters didn’t execute the most basic steps in seizing power, like securing Erdogan and other top officials. Not a single member of his cabinet and inner-circle AKP party leadership was detained. Nor did coup plotters effectively take control of TV, radio and internet outlets. The government TRT station and CNN Turk were for a time occupied by alleged coup plotters, who quickly retreated as the putsch fell apart.

As a result, Erdogan and a slew of his key ministers were able to make statements and appeals to loyalists on television in the chaotic early hours Friday night. Any reasonably organized coup attempt – and Turkey has a significant history of successful military coups over the years - would have made cutting off such communication a top priority, according to both advocates and deniers of the “staged coup” theory.

Coup plotters also failed to secure most airports and other transportation hubs, didn’t occupy or attack Erdogan’s $600 million presidential palace, and failed to intercept his plane before, during or after he flew from one of the country’s busiest and most accessible airports back to Istanbul. This despite the supposed active participation of top generals in Turkey’s Air Force, which maintains a fleet of F-16 aircraft easily capable of tracking, intercepting or – if it came to it – shooting down Erdogan’s plane.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan denies he was behind the coup attempt. (Associated Press)

Even the aggressive actions that were allegedly taken by the coup plotters – attacking the mostly empty parliament building in Ankara, occupying Ataturk International Airport but conveniently leaving in time for Erdogan to land his plane there – have raised much suspicion among the president’s many opponents.

The man Erdogan claimed to be the mastermind of the coup, U.S.-based cleric Fetullah Gulen, issued a statement strongly denying any role in the action, and said what many Turks were already expressing from the moment the news broke.

“There is a possibility that it could be a staged coup,” Gulen told reporters from his Pennsylvania compound on Saturday.

In a televised interview after regaining power, Erdogan angrily denied staging a coup attempt, and noted two of his bodyguards were killed when he narrowly escaped the Mediterranean villa where he was vacationing. The attack on the villa came only after he had left for the airport – even though it was publicly known exactly where he was staying – which has only fueled more skepticism about his role in the plot.

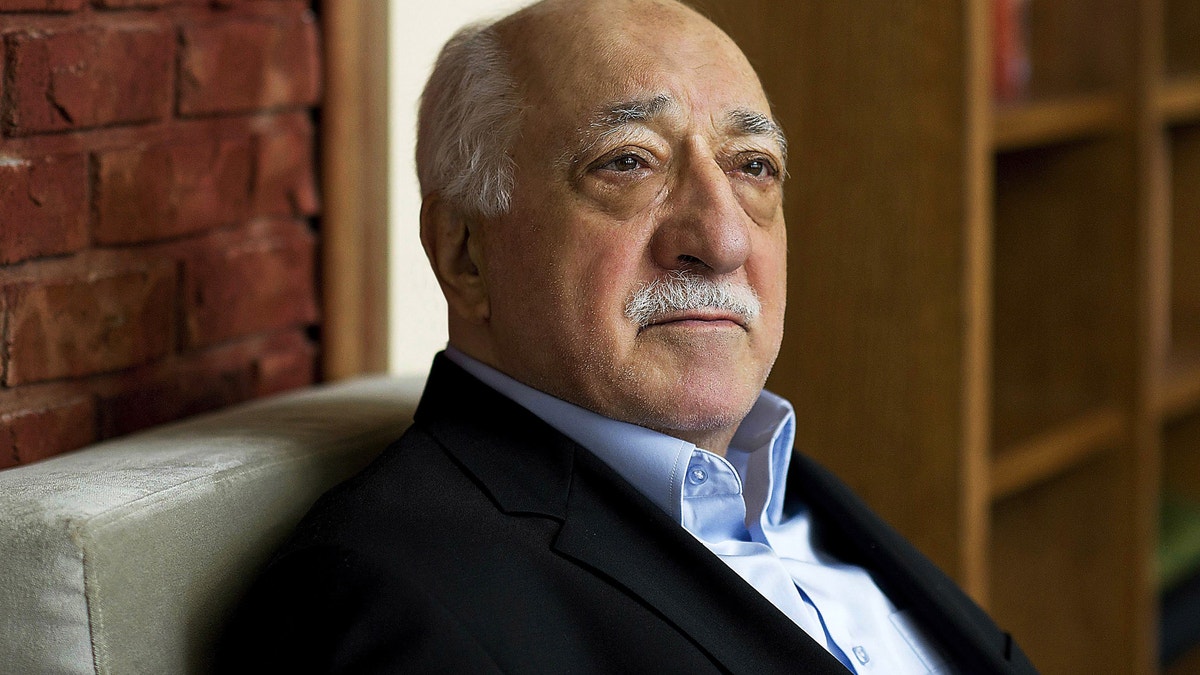

FILE - In this March 15, 2014, file photo, Turkish Islamic preacher Fethullah Gulen is pictured at his residence in Saylorsburg, Pa. Gulen is charged in Turkey with plotting to overthrow the government in a case his supporters call politically motivated. (AP Photo/Selahattin Sevi, File)

“That’s misinformation,” Erdogan said. “How can you plan such a thing? How can you plan for so many civilians to lose their lives – 208 civilians dying, 1,500 people lying on the ground trying to block tanks – how can you do that?”

Others argue there are good reasons to believe the failed coup was exactly what Erdogan claimed it was: an effort by a small faction within the military to seize power. While Erdogan’s increasing authoritarianism has not lessened his Islamist religious base, Turkish secularists are still strongly represented in the military.

Others believe the most plausible scenario may lie between the two theories: The attempted coup may have begun as an independent and organic movement, but in the hours or days before it was executed Erdogan was tipped off. He then allegedly allowed it to unfold in order to draw out his enemies.

Indeed, the Turkish military acknowledged Tuesday it had received intelligence some six hours in advance that a rogue element planned to mount a coup.

In the initial uncertain hours, it appeared to many the coup had succeeded. The plotters announced the military had taken control of the government and, with Erdogan on vacation in the seaside village of Marmaris, emboldened collaborators and sympathizers may have revealed themselves.

Whether the coup attempt was authentic, staged or tolerated, Erdogan has taken full advantage. On Tuesday, the government escalated its crackdown on people it claims have ties to Gulen, firing nearly 24,000 teachers and Interior Ministry workers, and demanding the resignations of another 1,577 university deans.

The latest purge was in addition to the roughly 9,000 people who have been detained by the government, including police, judges, prosecutors, religious figures and others.

Turkey's state-run Anadolu news agency says courts have also ordered 85 generals and admirals jailed pending trial over their roles in the coup attempt.

“You cannot deny how strong Erdogan is,” said a 38-year-old Istanbul-based professor, speaking under the condition of anonymity. “He has incredible control over almost all state institutions. So, the idea that Erdogan might have looked the other way while a small faction within the army planned this coup would not at all surprise me.

“After all, look at the outcome; he is perhaps more popular than he has ever been, he is able to implement his own agenda, run the show as he likes, and [do not be] surprised to see a presidential system, or at least a referendum for it, announcement coming up soon,” he added.