CULIACÁN – Even in death, Mexico’s drug lords can’t resist showing off the enormous power and wealth obtained thanks to their murderous careers.

In a cemetery on the outskirts of Culiacán, capital of the Mexican state of Sinaloa and home of the infamous cartel of the same name, some of the most elaborate and expensive mausoleums in the world mark the final resting place of dozens of former ‘narcotraficantes’ - or narcos.

Costing up to $500,000 each and featuring gold-plated domes, Italian marble and luxuries like wifi, air conditioning and satellite TV, many of the tombs at the Jardines del Humaya are like mini-mansions.

But the gaudiness at the cemetery 15 minutes’ drive from the center of Culiacán hides the grisly reality of the lives of many of their inhabitants.

Fox News visited early in the morning with journalist and Culiacán native Miguel Angel Vega – early because come the afternoon and evening friends and family are known to hold parties for the deceased at their gravesides and some do not take kindly to visitors.

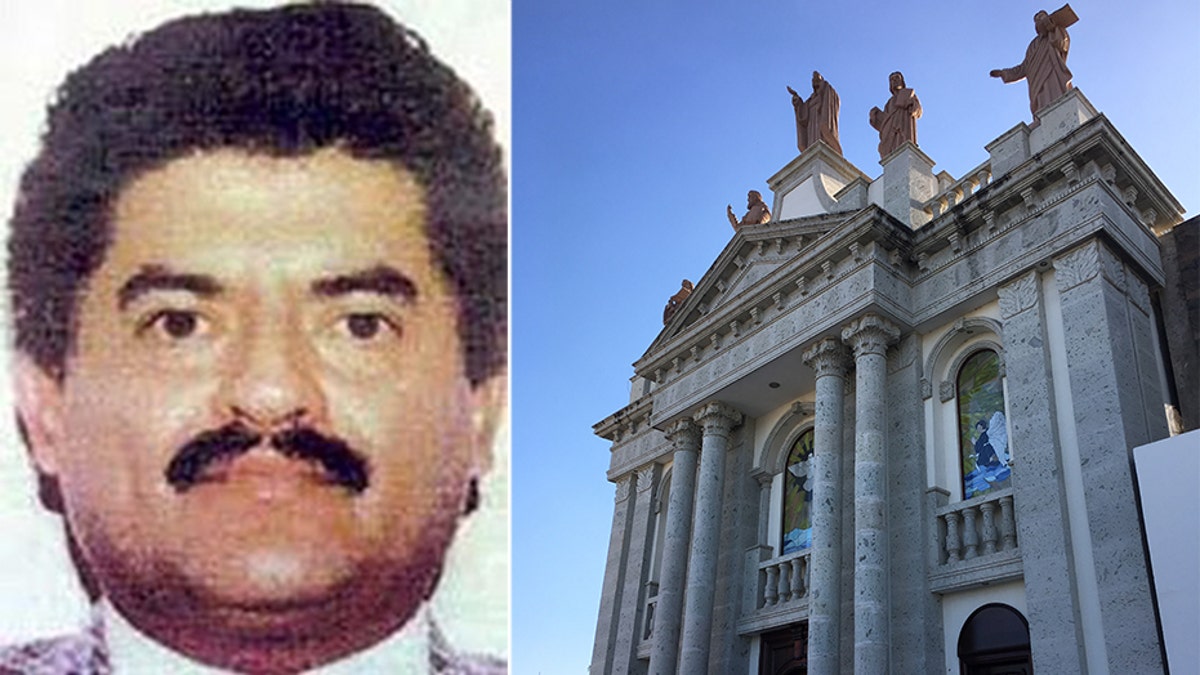

Manuel Torres Félix (right) was a Sinaloa Cartel capo known as 'The Crazy One' for his violent rages. He was gunned down and killed by the Mexican army in October 2012; his tomb (left) comes complete with a balcony and Greek pillars (Tim MacFarlan/handout)

The first rows of graves near the entrance are modest, most of them for professional Sinaloans who had nothing to do with the drug trade but were able to afford to be buried in a private cemetery such as this one.

Across an expanse of well-kept grass however are the ranks of much larger mausoleums, home to several former narcos.

“It’s a way of showing their power – it’s a competition, man. ‘Mine’s going to be bigger than yours,’” Vega said.

The plots are 80,000 pesos each ($4,200), more than many Sinaloans make in a year.

But you need 10 to build a big tomb, and some stretch into the high six figures.

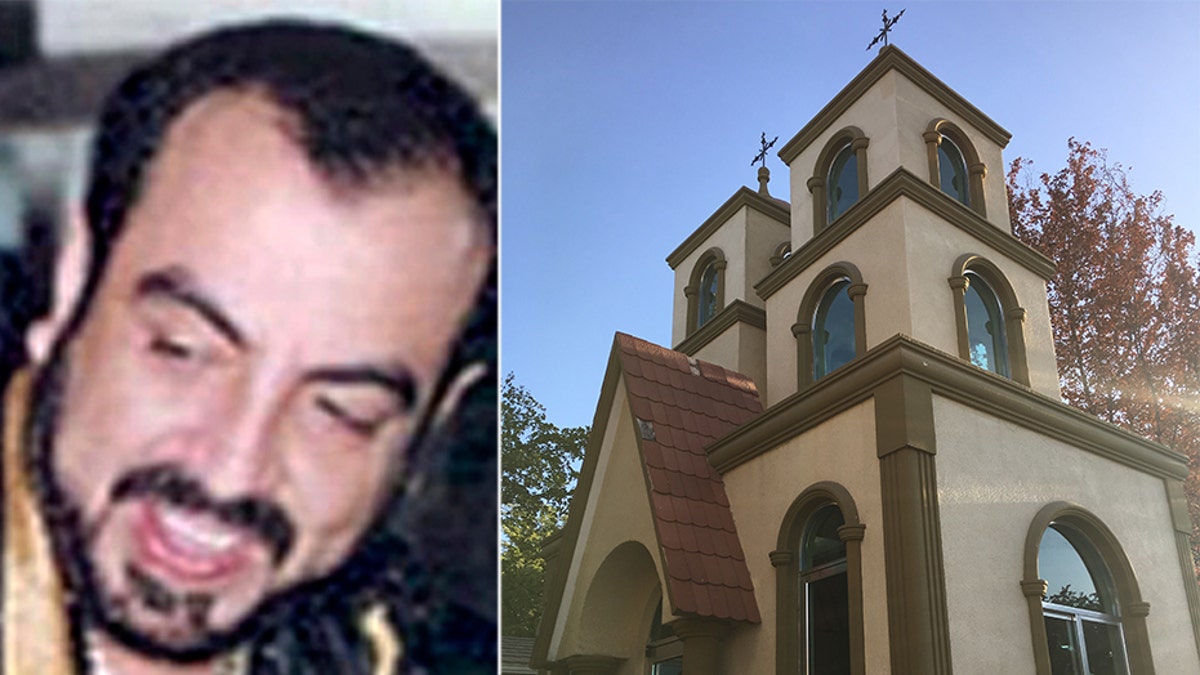

Arturo Beltrán Leyva (left) was a close associate of El Chapo until they fell out in 2008 and he split from Sinaloa to form his own Beltrán Leyva Cartel. He was killed in a raid by 200 Mexican marines in December 2009 (Handout/Tim MacFarlan)

“The bigger the space, the more expensive it is.”

LOCATION SCOUT FOR NETFLIX'S 'NARCOS' SHOT DEAD IN MEXICO

The dead drug traffickers here all had some involvement with the Sinaloa Cartel, widely believed to be the most powerful and far-reaching criminal organization in the world.

Believed to have been founded by Joaquin ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán in 1988, who is now incarcerated in a New York jail awaiting trial, its slain members soon began filling up the Jardines del Humaya.

But it was after then-president of Mexico Felipe Calderón mobilized the army to target the major cartels in 2006 that the number of deaths really started to mount.

The country’s War on Drugs has since claimed upwards of 200,000 lives, many of them in operations for or against the Sinaloa Cartel.

During that time the cartel has fractured, famously in 2008 when key capo Arturo Beltrán Leyva fell out with El Chapo, whom he believed had given up his brother Alfredo to the authorities.

DEA SPECIAL AGENT WHO CAUGHT EL CHAPO SHARES HIS STORY

Arturo started his own Beltrán Leyva Cartel but was killed in a raid by 200 Mexican marines in December 2009.

His tomb is surprisingly modest for the narco once known as ‘jefe de jefes’ or ‘boss of bosses’.

But a month after he was interred the severed head of a man was found placed in front of his mausoleum, his headless body dumped atop the tomb of a rival trafficker.

Everywhere the sun-dappled cemetery has similar tales of horror.

Perhaps the worst surrounds the family of Héctor Luis Palma Salazar, alias ‘El Guero’, or ‘Blondie’, who was a key early associate of El Chapo as he built up the Sinaloa Cartel in the late 1980s and 1990s.

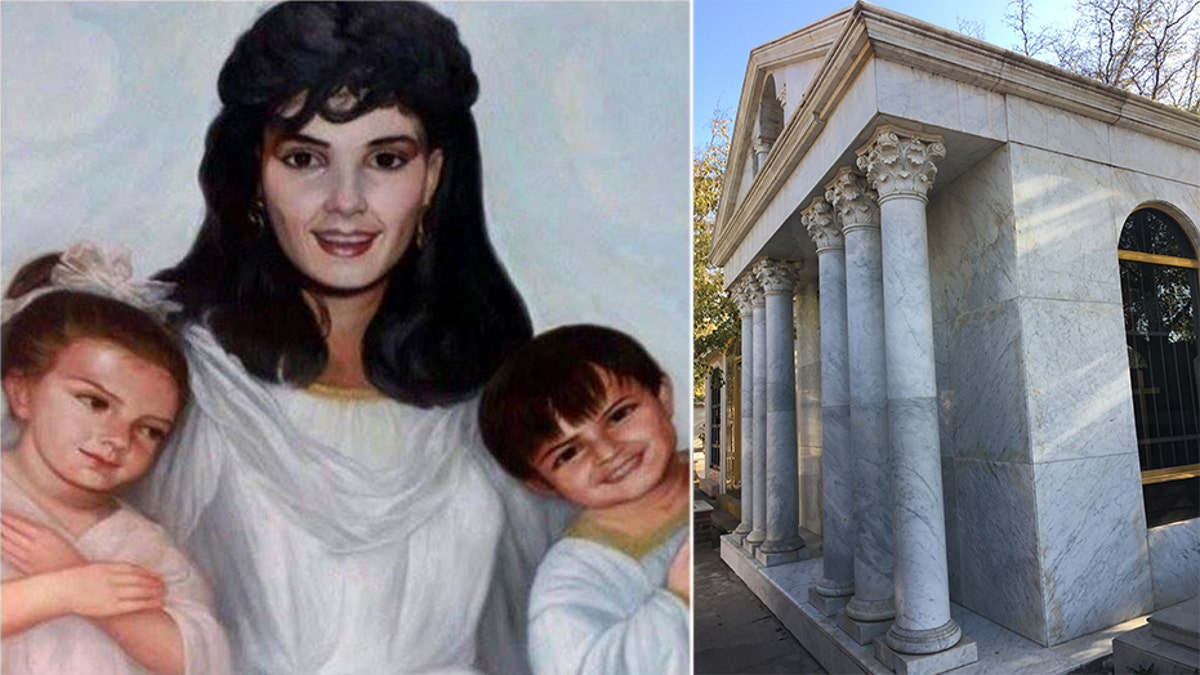

Salazar, who is still alive and in prison in Mexico, had a small tomb built for his wife and two young children on the edge of Jardines del Humaya.

In the mid-1980s Guadalupe Leija Serrano ran off to Venezuela with drug trafficker Rafael Enrique Clavel, taking with her the two young children she had with Salazar, Nataly and Jesús.

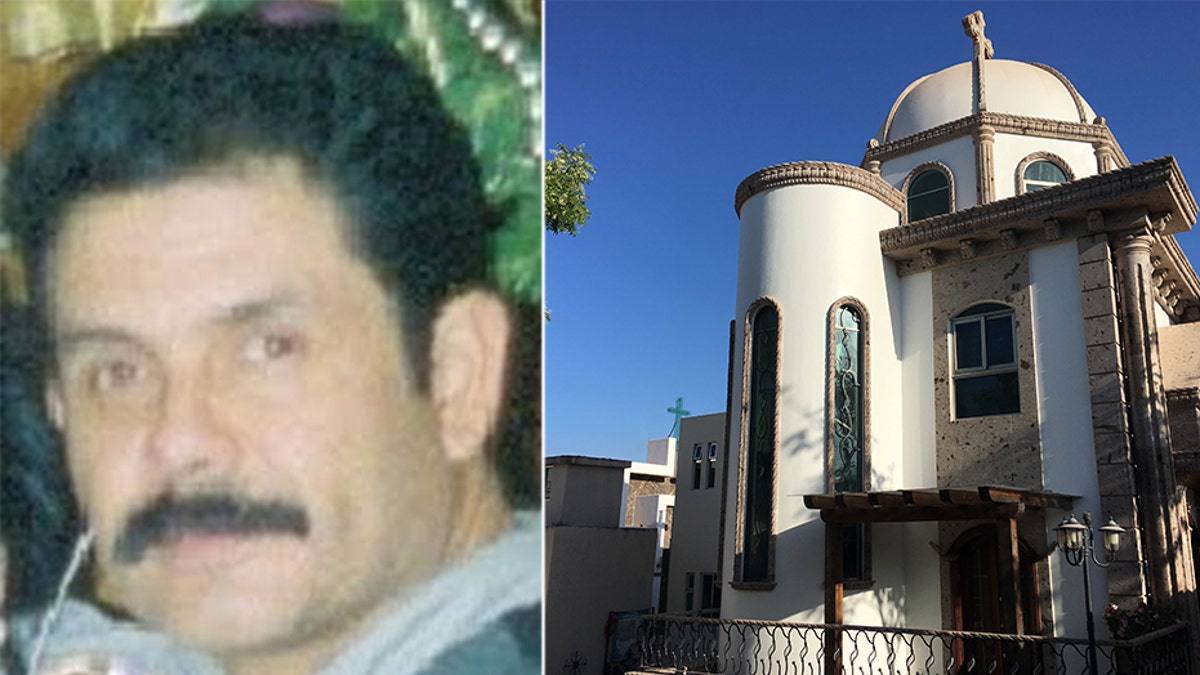

Ignacio 'Nacho' Coronel Villarreal was a high ranking Sinaloa Cartel capo known as the 'King of Crystal' for his domination of meth production and trafficking. He was killed in a shootout with the Mexican army in July 2010 (Handout/Tim MacFarlan)

But Clavel, a former associate of Salazar, murdered Guadalupe and had her severed head shipped to Salazar in a box, reportedly on the orders of Guadalajara Cartel head Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo.

NC TOWN BATTLES OPIOID EPIDEMIC BY USING ROBOTS TO TEST PEOPLE'S POOP

Days later, Clavel threw Salazar’s drugged children to their deaths off a bridge near the Colombian border, reportedly sending a video of him doing so to Salazar.

Guadalupe Leija Serrano was the wife of Héctor Luis Palma Salazar, 'El Guero'. She and her two young children Nataly and Héctor were all murdered by a Venezuelan drug trafficker to get at El Guero, who was sent the severed head of his wife in a box; In the cupola of their small mausoleum, Guadalupe and her children are depicted in a painting as angels seated in heaven (left) (Tim MacFarlan)

In the cupola of their small mausoleum, Guadalupe and her children are depicted in a painting as angels seated in heaven.

Many of the narco tombs are far less modest, including a Taj Mahal copy complete with air conditioning units and windows in the shape of the cross on the side of this replica of Islam’s most famous piece of architecture.

Karla Minerva Gutiérrez Guerra is a teacher in psychotherapy at the Autonomous University of Sinaloa in Culiacán and a former teacher in criminology.

This is the tomb of Ernesto Guzmán Hidalgo, the half brother of El Chapo, believed to have been killed on the orders of Chapo's older brother Aureliano Guzmán in April 2015 (Tim MacFarlan)

“These people who dedicate themselves to drug trafficking in an unconscious way feel guilty for the damage they have done, and their families too,” she said.

"One way to make amends for this guilt is to make these vast and ostentatious tombs.

“They also generally donate a lot of money to the church as if they are paying for their guilt, for a place in heaven. A lot of them are very religious.”

But aside from the guilt the giant tombs are also exercises in showing off.

“They demonstrate their riches and power – the bigger the tomb, the more powerful the incumbent,” Guerra added. “Usually narcos are killed by other narcos in fights over territory. They build these tombs because they don’t want to be forgotten.

It is not known for sure but this is thought to be the tomb of Juan Jose Esparragoza Moreno, 'El Azul', a key Sinaloa Cartel capo said to have died of a heart attack in June 2014 but believed by many to still be at large (Handout/Tim MacFarlan)

“It also because they are egocentrics and psychopaths so they think about what benefits them.

“This self-centeredness makes them want to feel more important than others and better than common people.

“Additionally they feel they have to compete with other narcos.”

They are egocentrics and psychopaths so they think about what benefits them. This self-centerdness makes them want to feel more important than others and better than common people

Two construction workers busy touching up the walls of a tomb with a two-story atrium, complete with giant fluorescent cross, explain that the plot they are working on will include a bathroom and air-conditioning.

“This one cost a mere $75,000,” one of the construction workers says.

Outside there are lampposts, complete with surveillance cameras, and palm trees. The marble inside is Carrara, imported from Italy.

Neither of the workers wants to give their names, or say who the tomb belongs to: “It’s for our security, we don’t want problems,” one says.

No expense spared: This mausoleum cost $500,000, according to construction workers, although it's unclear who it has been built in honor of (Tim MacFarlan)

But he does say the tomb’s owner is not yet deceased.

He adds: “It’s an empty grave. These people have so much money they can spend hundreds of thousands of dollars just in case something happens.

“They build these massive tombs when they are still alive. What’s the point of having all that money?

“It’s a short career.”