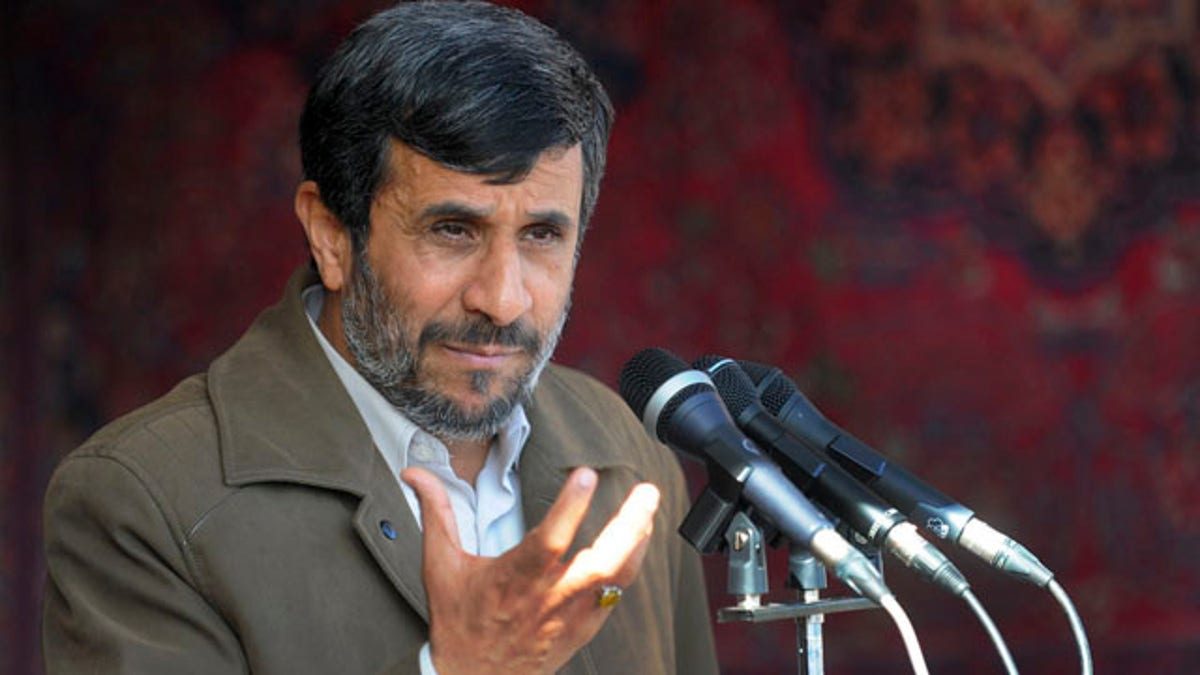

Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (AP)

DUBAI, United Arab Emirates – In one of Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's first major policy speeches back in 2005, he laid out some bedrock principles: Iran will never halt uranium enrichment and the West needs to deal with the Islamic Republic on equal footing.

Jump ahead to today, and Iran's stance remains unchanged as it and world powers prepare to resume talks on Tehran's nuclear program on Dec. 5. That puts the new round of negotiations already on shaky ground.

Iran's dealings with the West often can appear erratic and mystifying — often it seems to avoid straight answers in negotiations or to throw unexpected ideas into the agenda. But behind the twists and turns, it has stuck to the principles in Ahmadinejad's speech five years ago: Iran's deep pride in its mastery of atomic technology and its self-image as an emerging global force that deserves respect.

Iran has shown its willingness to suffer repeated rounds of U.N. financial sanctions, Western condemnation and even tension with allies like Russia and China to stick by what it wants.

"It gets down to a test of wills and Iran has become quite good at holding its ground," said William O. Beeman, a University of Minnesota professor who has written on Iranian affairs.

In the negotiations, the United States and its allies are seeking to get Iran to halt uranium enrichment, fearing that Iran secretly intends to use the process to produce a nuclear weapon. Tehran denies any such intention and has unwaveringly rejected halting enrichment, saying it has a right to use it to produce fuel for a nuclear reactor.

In the first round of nuclear talks last year, Iran showed its deftness at buying time. Its envoys carefully avoided being pinned down by international proposals. At the same time, they cooked up counteroffers and took various potshots at Washington and its allies along the way.

The talks eventually collapsed and Iran was slapped with even tighter sanctions, which have led dozens of major European and Asian firms to pull out of the Iranian oil and consumer markets.

Still, there are no hints that Iran will show any new flexibility in the upcoming negotiations. They appear, in fact, to be shaping up as an exercise in crossed-wires conversations.

Earlier this month, Ahmadinejad repeated Iran's baseline position: It won't consider backing off its right to enrich uranium as a signer of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. Iran's leadership has so far succeeded in turning this stance in a point of national unity and dignity, even among most internal opponents.

This is a direct shot at the U.N.-drafted proposal supported by Washington and others to offer Iran reactor-ready fuel in exchange for halting uranium enrichment and moving its stockpile of low-enriched uranium out of the country.

Instead, Iran wants to restart talks with the United States and others with a freeform agenda on international political and security issues. Ahmadinejad has called on world powers to take "side of justice" in the talks.

In the parlance of the Islamic Republic, that covers a grab bag of grievances over the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, U.S. domination of the world scene, human rights violations in the West, and Israel's undeclared nuclear arsenal.

It's unclear how much patience the United States and others will have for the Iranian soapbox. But the State Department appears eager to get some kind of dialogue going and then try to steer it to the nuclear impasse.

"We're trying to get them back to the negotiating table," said State Department spokesman Mark Toner last week. "We're going to raise the nuclear issue, and I think they're well aware of that."

Yet there could be more than Iranian foot-dragging blocking any headway.

The mounting pressures from sanctions could be opening more rifts among Iran's leaders on whether to stay firm or open up serious negotiations, said Nicholas Burns, a former top State Department diplomat who was the Bush administration's point man on Iran from 2005 to 2008.

"This internal turmoil does not bode well for the upcoming negotiations as the Iranian leadership will likely be unable to speak with one voice," said Burns, a professor of diplomacy and international politics at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government.

The two sides have not even found agreement on the location for the talks.

The so-called 5-plus-1 group — the five permanent Security Council members plus Germany — want a venue in Switzerland or Vienna, home of the U.N.'s nuclear watchdog agency. Iran has pressed for Istanbul, which would give them Turkey as an ally in the wings.

It also would allow Iran to showcase that it still has some influential friends. NATO-member Turkey is fast becoming a valued political and trading partner for Iran at a time when Tehran's rulers are feeling a chill from old stalwarts.

Russia called off the delivery of its S-300 anti-aircraft missile system because of U.N. sanctions — a decision that so angered Iranian officials that Ahmadinejad accused the Kremlin of being "influenced by Satan."

China, meanwhile, has promised to abide by international sanctions in a potentially serious blow to an Iranian economy awash with Chinese goods and relying on Beijing's help in road and rail construction.

The sense of eroding international ties may eventually prove a stronger motivator for Iran to reopen talks than the prospect of more sanctions, said Ehsan Ahrari, an international affairs analyst based in Alexandria, Virginia.

"So Iran feels abandoned," he said. "It might not have much of a choice to start the dialogue and see whether it can stall for another year."

Meir Javedanfar, an Iranian-born political analyst based in Israel, believes Iran is offering talks out of fear of losing further ground in its critical relationship with China.

"(Iran) is interested in the new round of talks not because it wants to offer a new compromise for the nuclear program. Rather, it wants to avoid isolation," said Javedanfar.

___

Associated Press writer Matthew Lee in Washington contributed to this report.