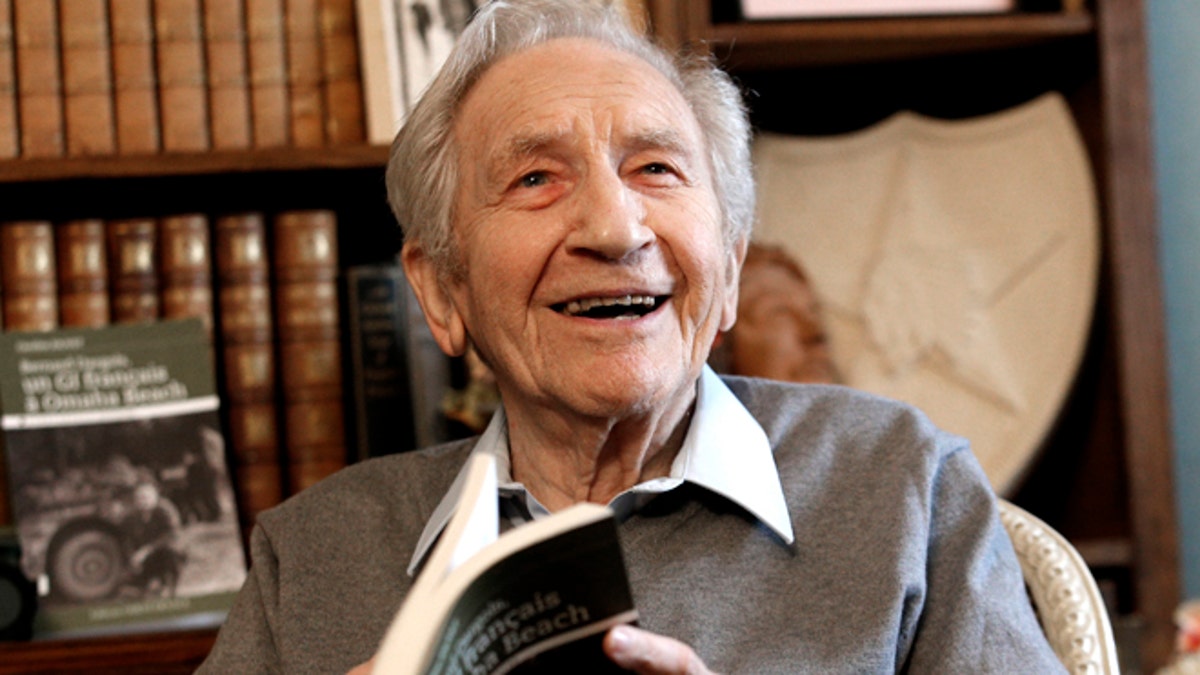

May 8, 2014: Bernard Dargols poses during an interview with the Associated Press at his home in La Garenne-Colombes, outside Paris, France. When he left Paris at age 18, the plan was to go to New York for a year and learn his fathers sewing machine trade. Six years later, Bernard Dargols found himself crossing the Channel in a U.S. Army uniform, sloshing ashore on Omaha Beach to a homeland that had persecuted his Jewish family. (AP)

PARIS – When he left Paris at age 18, the plan was to go to New York for a year and learn his father's sewing machine trade. Six years later, Bernard Dargols found himself crossing the Channel in a U.S. Army uniform, sloshing ashore on Omaha Beach to a homeland that had persecuted his Jewish family.

Dargols' journey from Paris to New York and back ended when he drove his Army jeep into a courtyard in the recently liberated French capital, striding upstairs into a darkened apartment and into the arms of his weeping mother. Until that moment, he hadn't known whether she had survived the Nazi occupation.

"She hadn't seen me in six years and I saw she was alive," Dargols said in an interview ahead of the 70th anniversary of the D-Day invasion that helped defeat the Nazis.

Once back, he learned about the cousins who had been taken away to concentration camps, and about his grandfather, who had managed to escape the French transit camp at Drancy. He learned his father's sewing machine shop had been seized. He saw a city empty of non-military traffic, because there was no more gasoline.

"I had such a hatred of the German army," he said.

Emotion overcomes him even now, at age 94, when he thinks back to the increasingly desperate letters from his family, describing Gestapo sweeps and the racial laws that robbed his father of his shop. His father and brothers had fled. Their mother stayed behind to care for both sets of grandparents, too frail to escape.

Today Dargols avoids the company of Germans his own age.

___

Dargols does not get seasick. He has an uncanny recall of topography, numbers and names. He has an ironic sense of humor and is multilingual, thanks to his English-born mother and Yiddish from his father's family. All of these qualities would serve the Allies well.

In New York, after France's Vichy government sided with the Germans, the French consultate in New York sent Dargols a draft summons. He ignored it.

Dargols was determined to fight — but certainly not with the Nazis.

He considered joining the resistance Free French forces, but had heard that leader Charles de Gaulle didn't get along with the Americans and British. He considered the British but they only wanted sailors, and he wasn't interested. Then his friends said they were sure the United States would soon jump into the war — so he got American citizenship and signed up for the U.S. Army.

The call-up came soon, shortly after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Dargols found himself in Camp Croft basic training in South Carolina, with a blank map of France in front of him on a desk.

"A neutral map, as they say, just the cities marked 1234 and the rivers marked ABCD," Dargols recounts. His successful test placing names to places got him sent to military intelligence training, where he briefly taught French to other GIs and learned to distinguish the sounds of different German aircraft. He feared he'd end up as an interpreter, writing and translating papers.

"That was exactly what I didn't want. I wanted to fight," he said. Wry and still combative seven decades later, he added: "If I look at myself in the mirror, I can't understand how I was so willing to fight. But I think if I was 24 again, I would fight again."

He was sent to England, where he was under orders to say nothing about his work for the military.

His father and two younger brothers had managed to escape France on an 18-month journey that took them through Cuba, and eventually to New York. They moved into Dargols' apartment just as he was leaving for basic training. Once he started intelligence work, his communications with them were cryptic by necessity.

"Do not worry if my address changes yet again, it means nothing," he wrote his father from England on May 22, 1944. "I have every reason, without being able to explain, to be happy."

___

And so on June 5, 1944, Dargols found himself in a boat as a staff sergeant for the U.S. Army, part of a small intelligence unit that also included Hans Namuth, a German-born photographer who defied his father by turning against the Nazis and emigrating to the United States. They landed in Normandy on June 8 — D-Day Plus 2.

His colonel's orders were to head into the village of Formigny and learn about the German forces in the area: "You know what questions to ask ... If you're not here after two hours, we forget about you." After that successful mission, the ritual repeated itself regularly — with the same two-hour rule.

The locals didn't know what to make of Dargols' Army jeep, with "La Bastille" proudly painted on the side in honor of its Gallic sergeant.

"Within a few minutes ... I was surrounded by old men who wanted to kiss me as a liberator. It was very moving," he said. He had no problem persuading people to share what they knew about the German forces nearby, and made it back to base in time, every time.

The road he took from Omaha Beach has borne his name since 2008.

Dargols made it to Paris in September, and that fall he transferred to the U.S. Counterintelligence Corps. During that time, his younger brother Simon landed with American forces in Marseille, returning to the same port city he had escaped from three years before.

Simon's unit ended up outside Landsberg, Germany, stumbling upon part of the Dachau concentration camp, where prisoners embraced him when they learned he spoke Yiddish and was there to free them.

Namuth, the German who traveled across the Channel with Bernard Dargols, returned to the United States after his service and turned his military experience as a photographer into a career taking portraits and making films, famously documenting Jackson Pollack splattering paint.

Bernard Dargols returned to New York, and married his French fiancee. The couple eventually returned and settled in the land of their birth. His father also returned to France — where he was reunited with his wife and reopened his shop.

Dargols killed no Germans during his time in the Army; his job was to gather information.

"I wanted to kill so many Germans. I was not given the chance to kill one," he said. Today, in his twilight years, he does not regret that, but neither does he forget what happened to his country — and his family.

"I don't wish youngsters to be faced with the same tragedy as I was faced, and not (be) prepared to be a soldier."