Joaquin ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán has finally been convicted of running a massive drug smuggling operation as head of Mexico's notorious Sinaloa Cartel - but even though he will likely spend the rest of his life behind bars, but experts believe the story is far from over.

Journalist and author Malcolm Beith, who has covered Mexico's efforts to combat organized crime for more than a decade, has written a book on the hunt for El Chapo, and attended the kingpin's trial in Brooklyn, thinks we'll be hearing more from the kingpin in future.

“He’s off to jail, no doubt, for life but he’s got kids who are now American citizens; he’s got a wife who’s legally here; he’s got lawyers," he told Fox News.

“They have already threatened to sue people in Mexico for defaming his name.”

America Armenta, a reporter for El Debate newspaper, based in the Sinaloan capital Culiacán, says that partly through the help of his wife Emma Coronel, who has been a fixture at his 11-week trial, El Chapo remains “very well seen” by many in his home state.

Emma Coronel Aispuro, wife of Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman, leaves federal court in New York, Tuesday, Feb. 12, 2019. (AP)

“Emma Coronel is a person who loves the spotlight," Armenta said. “On November 2 last year she was seen in public handing out welfare to help people [Sinaloa]. She was giving medicine to sick children.

“She is associated directly with her husband and they have always been a strong presence in Sinaloa, including while Chapo has been in prison and since the beginning of the trial in Brooklyn.

“They have a lot of acceptance in Sinaloan society. Emma Coronel is popular as well because before being the wife of Guzmán Loera she was a candidate for Miss Sinaloa, for the title of the most beautiful woman in the state.

TED CRUZ WANTS 'EL CHAPO' AND DRUG LORDS TO PAY FOR BORDER WALL

“She is therefore popular on her own and with El Chapo. There is a section of society that still supports him.”

Juan Carlos Ayala Barrón is a professor at the Autonomous University of Sinaloa in Culiacán, who specializes in "narco cultura", the mythology that has sprung up around drug traffickers.

Professor Barrón grew up in the rural St Ignacio municipality of the northwestern Pacific state, an area long renowned for its opium and marijuana production.

“For many El Chapo has become a unique figure in our citizenry and people respect him because, well, on some occasions groups of drug traffickers like his have provided assistance to and helped and supported places where the government has not reached," he told Fox News.

“It has been a means of survival for people and a solution to some of the problems experienced by different communities. There are many people who regret the result of this trial.”

'EL CHAPO' TRIAL SEES DRUG LORD'S TEXTS WITH WIFE - AND 'WILD BEAST' MISTRESS

In this Jan. 19, 2017 photo provided by the United States Drug Enforcement Administration, Mexican drug kingpin Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman arrives at Long Island MacArthur Airport in Ronkonkoma, N.Y., after being extradited to the United States to face drug trafficking charges. (United States Drug Enforcement Administration via AP)

The influence of El Chapo’s family on the drug empire he once controlled is still very much felt through two of his sons, Ivan Archivaldo and Jesus Alfredo, whom he had with his first wife Alejandrina Salazar Hernández.

The pair are collectively known as the ‘Chapitos,’ or ‘little Chapos.’ El Chapo has reportedly fathered up to 12-13 children, including the seven-year-old twin daughters he has with Coronel.

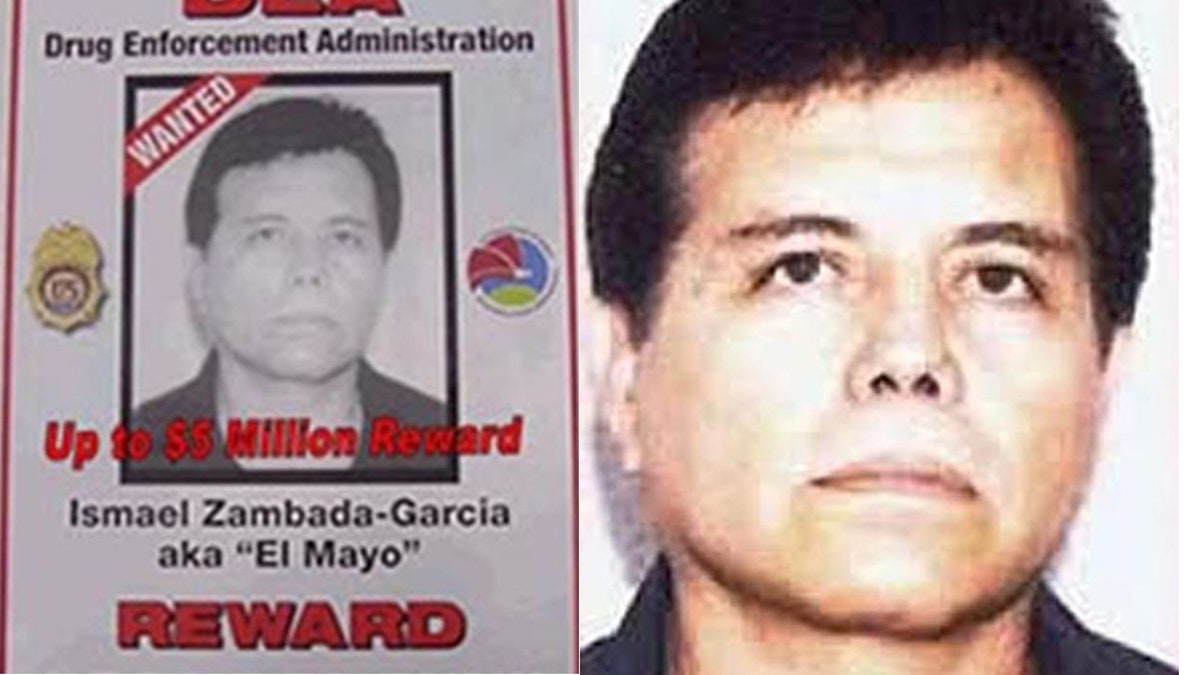

The Chapitos are known to be working in partnership with Ismael ‘El Mayo’ Zambada, his long-time compatriot who has taken over as head of the Sinaloa Cartel.

Ismael Bojorquez, director of the Río Doce newspaper in Culiacán, told the Associated Press the Chapitos "control street-level drug dealing, especially in Culiacán, and the defense operations, the weapons," while "El Mayo takes care of the big deals."

Bojorquez’s friend Javier Valdez, an internationally renowned Sinaloan journalist with whom he co-founded Río Doce, was shot dead in 2017 allegedly on the Chapitos’ orders, it emerged during El Chapo’s trial.

They are still widely believed to control street-level dealing, particularly in Culiacán, and have a strong role in weapons procurement. The cartel itself is still a major force in the Mexican underworld, controlling an army of hitmen, enforcers and money launderers, while its distribution network is still thriving.

The sway they still have, and the extent to which Sinaloa Cartel bribes have allegedly reached the highest levels of the Mexican government – something El Chapo’s trial laid bare – are strong reasons why he could never have been tried in Mexico, let alone Culiacán.

Jesus Alfredo Guzman-Salazar, who is on the DEA's Most Wanted list (DEA)

“For the moment, I don’t believe [a trial in Mexico] is possible," Armenta said. “What has come out from many of the witnesses in the trial in Brooklyn, though of course they are not the most reliable sources, is that people at all levels of the Mexican government have been receiving money [from the Sinaloa Cartel].

“If that’s true or if it’s a lie, every one of those in power who allegedly accepted money should be investigated. Millions of pesos are involved.”

SINALOA CARTEL MARCHES ON AFTER EL CHAPO ARREST, CONVICTION

Thus far, there have been no mass demonstrations of support for El Chapo in Sinaloa, according to Armenta, although there were marches back in 2014 and 2015.

The Chapitos are known to be working in partnership with Ismael ‘El Mayo’ Zambada (pictured), his long-time compatriot who has taken over as head of the Sinaloa Cartel.

The attitude of the Mexican public at large to the Brooklyn proceedings appears to have been one of indifference, reflected in often sparse coverage by Mexican media.

“My general sense from talking just to Mexican friends and other journalists is no one cares anymore. I think that’s actually wrong, I think they should care,” Beith said.

“This is hugely important for Mexico actually because if Mexico’s judicial system is to get a boost from us [the US], they want to be opening up their courts.

“They want someone like Chapo to someday, maybe 50 years from now, not to face a court in Brooklyn but in Culiacán. That would be huge.

“That basically should be the goal but are we going to end the drug war with Chapo’s conviction? No, it’s just a stupid argument, we’re past that.”

Violence in Sinaloa, meanwhile, shows no signs of ending. The state has seen a recent spike in robberies, carjackings and femicides not obviously related to drug trafficking.

With the Sinaloa Cartel chastened to some extent by the loss of its leader, there are worries about the kind of groups that could seek to move in on their turf.

“Here in Sinaloa we have become accustomed to living around these groups [that make up the Sinaloa Cartel]," says Professor Barrón. “They are groups that for decades maintained a certain stability around what are the zones of conflict in the state.

“They did not allow other criminal groups to enter but the fear people have now is precisely that: who could enter this area?

“What about groups like the Zetas or Cartel Jalisco [CJNG]? They are brutally violent groups so this is the fear of many people.

“In other states we have seen waves of terrible violence with beheadings and dismemberments which are things that are very rare here.

“This is the uncertainty there is right now – people are wondering what comes next.”