US sounded alarm on Wuhan lab studying coronavirus two years ago, report says

State Department cables obtained by The Washington Post warned about the safety and security of coronavirus testing on bats in China in 2018; Gillian Turner reports.

Get all the latest news on coronavirus and more delivered daily to your inbox. Sign up here.

In early 2003, the onslaught of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) out of southern China became the first public health crisis of the 21st century.

Accusations of cover-ups orchestrated by the Chinese government, and a dangerously slow response from the World Health Organization (WHO), were ignited as panic seeped in and lives were lost.

Seventeen years later, the very same red flags have been raised – but there has been at least one glaring difference.

"WHO strongly criticized China for its lack of transparency and cooperation during the 2003 SARS outbreak," Brett Schaefer, Senior Research Fellow in International Regulatory Affairs at the Heritage Foundation, told Fox News. "[This] stands in sharp contrast to recent statements praising China for its COVID-19 response."

In recent months, China has been praised by WHO and other world figures for its quick, decisive, and candid reaction to coronavirus, officially termed COVID-19, as a potent change from its handling of SARS. But cracks in the honest and open theory are fast emerging.

CLICK HERE FOR COMPLETE CORONAVIRUS COVERAGE

In this Feb. 24, 2020, file photo, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director general of the World Health Organization (WHO), addresses a press conference about the update on COVID-19 at the agency's headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland. (Salvatore Di Nolfi/Keystone via AP, File)

SARS is also a novel coronavirus that can mutate into varying strains and cause deadly respiratory problems. Many of its victims went from having mild flu-like symptoms to their death beds and battling to breathe in the span of a few days.

So what happened all those years ago, and were lessons adequately learned and applied?

The first recorded case of something amiss was noted in November 2002 by health officials in Guangzhou city, Guangdong Province, the presumed origin of the new pathogen. But it was not until more than three months later – in mid-February 2003 -- that China's leadership reported a new virus to WHO, acknowledging that there had already been 300 cases and five known deaths of the new disease.

Just as evidence is starting to unfold of a Beijing cover-up, the Communist Party (CCP) leadership – then under President Hu Jintao – was similarly accused of hiding information, and the World Health Organization (WHO) was also skewered for inaction. But some experts note that they were working behind the scenes to build a file.

According to Ken Mahoney, of the Wall Street-based risk firm Mahoney Asset Management, when the Chinese government became aware of the first cases of a SARS, it failed to alert WHO, but WHO staff was monitoring Chinese medical message boards and eventually took all the information it had to China.

CORONAVIRUS CRISIS: WHAT HAPPENS NOW TRUMP HAS PULLED ITS MAJORITY FUNDING FROM THE WHO?

"However, in this crisis, reports of the virus were silenced for as long as six weeks, and action was not taken immediately. There is little doubt the WHO's silence has cost the world dearly, both economically and, more importantly, in lives lost," he observed. "The SARS response was led by WHO leader Gro Harlem Brundtland, and she accused China back then of withholding information. The outbreak might have been contained if the WHO had been effective at their mission at an earlier stage and encouraged China to let them come in as quickly as possible."

Chinese President Xi Jingping and U.S. President Donald Trump shake hands. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

It was in February 2003 when China first acknowledged SARS, although hospitals are said to have reported a strange new pneumonia to authorities some three months earlier. Days after notification from Beijing, WHO internally activated its global influenza laboratory network and called for heightened global surveillance on Feb. 19, 2003.

But even with a Beijing admission, it was two days later that the pathogen spread outside China's borders and killed hundreds.

On February 21, a 64-year-old Chinese medical doctor who had treated patients in Guangzhou and was incubating SARS traveled to Hong Kong. Within a 24-hour period, he had unknowingly transmitted the disease to 16 other guests on his floor at the Metropole Hotel.

The doctor fell gravely ill the following day and checked into a Hong Kong hospital, dying on March 4. The other infected guests – then with only mild symptoms – carried the virus to Toronto, Singapore, and Hanoi, or they entered hospitals in Hong Kong. A global outbreak was thus ignited. One of those guests, a businessman who went on to Hanoi and was admitted to the hospital on February 26, puzzled hospital staff so much that they allegedly reached out to the World Health Organization on February 28.

On March 12, WHO finally sounded the global alarm about a mystery virus, two days after China requested laboratory support. Days later, a worldwide travel advisory was issued by the organization. From April, a number of other warnings were sent out, cautioning people to avoid all but essential travel to impacted areas, which generally consisted of mainland China, Hong Kong, Canada and Taiwan.

CORONAVIRUS: US GIVES 10 TIMES THE AMOUNT OF MONEY TO WHO THAN CHINA

Questions were quickly raised as to how and why the contagion was allowed to escape China's borders.

Flashback: A family wear masks on a street in the Central business district of Hong Kong as an outbreak of SARS grips the territory in March 2003. (AFP via Getty)

At the time, WHO officials based out of headquarters in Switzerland sharply criticized China for withholding crucial information and keeping them in the dark, insisting that they acted as soon as they knew – but protocol prevents them from declaring travel warnings and health alerts until enough information has been gathered.

Yet other critics contended that WHO missed or dismissed warning signs – including from local media cautioning of an odd new pneumonia and rapid purchasing of anti-viral medications – that should have been picked up by its 30-person Beijing office or its partner laboratories. Furthermore, more than a month before that fateful Hong Kong visit, a doctor in Guangdong is said to have sent a letter in late January to health professionals in other provinces, outlining the symptoms, lack of responsive treatment and urging quarantine measures for those exhibiting signs.

WHO's decision-makers later claimed that they did not receive the memo.

"This was the first time a coronavirus had come to the attention as a pathogen that could spread around the world like this," Prof. David Heymann, who led WHO's infectious disease unit at the time of SARS, told the BBC. "So, in the beginning, it wasn't known what it was, and nobody really looked for coronaviruses such as they are doing now."

In April 2003, a well-known – and ultimately frustrated – Chinese doctor spoke out and accused the government of having obscured the virus. That month, an embarrassed China leadership apologized to the world and fired a number of health authorities, including its health minister and the mayor of Beijing, over their conduct. Similarly now, Beijing has axed several health and political figures in Hubei, where the current coronavirus started.

At a June 2003 conference in Kuala Lumpur, Chinese officials claimed that less than 350 people had died and that the outbreak was contained in the first three months, mostly to its starting point of Guangzhou. It was "Stage 2," health authorities vowed, three months after the first case that the "downward trend" was documented as a result of an improved national surveillance system. That system required measures such as daily temperature checks for children, tracing of the "mobile population," and the sealing off of known SARS clusters.

"Information was shared with WHO and shared on a daily basis," authorities claimed.

TRUMP ANNOUNCES US WILL HALT FUNDING TO WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION OVER CORONAVIRUS RESPONSE

The CCP pledged following the outbreak to improve its disease control system, establish an outbreak and alert system, and "enhance international cooperation." It was not until July 5, 2003, that WHO classified SARS as an epidemic – eight months after the first case.

But as the SARS pandemic died down, WHO's top-brass highlighted the importance of government transparency to avoid such a health crisis from retaking hold, and the CCP also pledged to combat the matter.

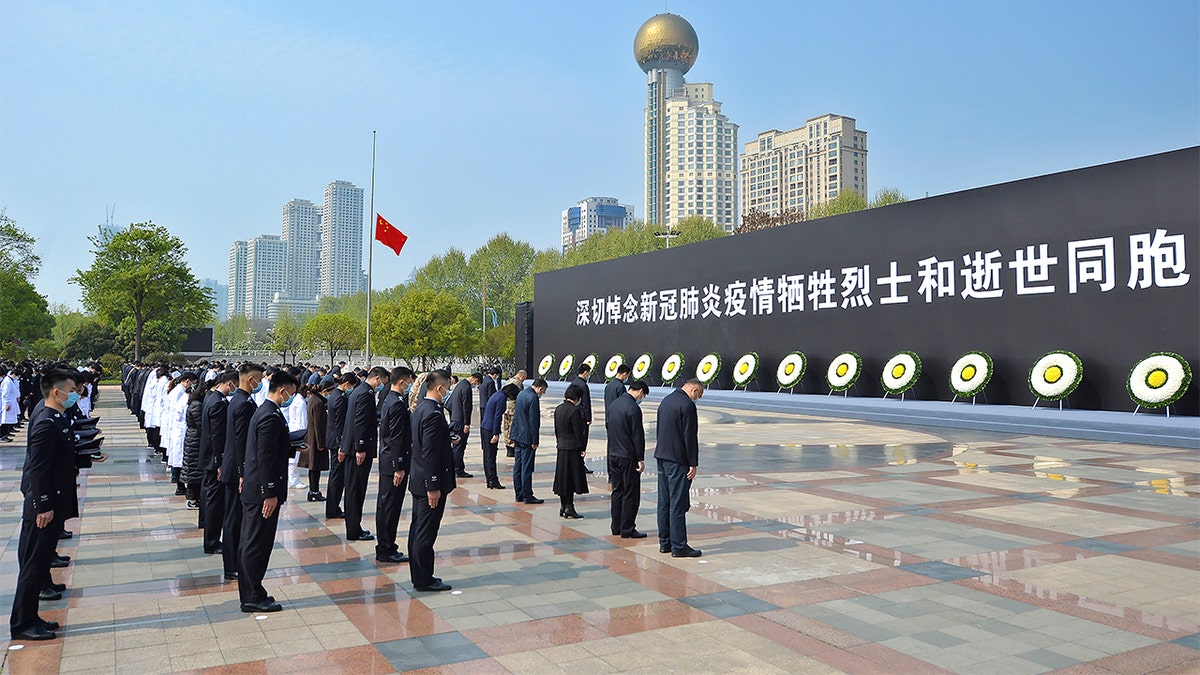

People bow their heads during a national moment of mourning for victims of coronavirus at an official ceremony in Wuhan. (AP)

Internally, it endeavored to establish a more robust surveillance system, creating an online channel that connects clinics and hospitals across the country to enable them to document cases in real time. The system was widely lauded by international health experts, and, while it was designed to avoid political interference, early admonitions of the current coronavirus were not submitted. Instead, it was through whistleblowers that information finally leaked out.

Furthermore, geopolitical analysts have alleged that the Chinese government only bolstered its grip of the information flow following the SARS disaster.

In 2006, one of the original Chinese physicians to have identified and worked on SARS decried the country's "dangerous" and "unsanitary" wet markets as a source of possible infection -- but the government failed to close them down. COVID-19 is believed to have stemmed from an infected bat at such a market in Wuhan, Hubei.

In the end, SARS infected around 8,000 people across some 29 countries, with an approximate 10 percent mortality rate – killing 800. By June 2003, it was classified as a "contained" epidemic. It never reached "pandemic" levels – a far cry from coronavirus, which has infected some 2 million people and killed more than 125,000.

With COVID-19, WHO was misled and kept at arms-length by China. They fell for China's version of events hook, line and sinker.

Yet in the SARS aftermath, public health professionals proclaimed that WHO had become especially active in "preparing for a possible return," concerned with "laboratory preparedness and planning to ensure rapid, sensitive, and specific early diagnosis.

The coronavirus that sparked SARS was later tracked to the feral civet cat, considered a delicacy by some. After the outbreak, China outlawed the slaughter and consumption of civet cats, and in early 2004, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States issued an import ban on the raccoon-like creatures.

According to Sara Abiola, assistant professor of Health Policy & Management at Columbia University, the actions of WHO through the SARS calamity were bolder in the early phase.

"The WHO took these actions even though they did not have formal authority to do so at the time and publicly criticized China," she noted. "Essentially, the WHO has even more avenues now through which to attempt to help control the global spread of infectious diseases now than it did during the SARS outbreak. However, no matter what the WHO mandates, it will always be limited by the sovereignty of its Member States and its budget. Its budget is not commensurate with its responsibilities; WHO controls only 30 percent of its budget, and Member States have co-opted WHO's agenda through earmarked funds."

Moreover, analysts highlight that WHO back then was not afraid to condemn China's obscuring ways, as the blatant lack of transparency from the country angered leaders around the world.

"With SARS, WHO stepped in and took charge by demanding data and action, and China complied. Because WHO aggressively intervened in China with the SARS outbreak, WHO was largely praised for preventing a global pandemic," contended Summer McGee, dean of the School of Health Sciences at the University of New Haven. "With COVID-19, WHO was misled and kept at arms-length by China. They fell for China's version of events hook, line and sinker."