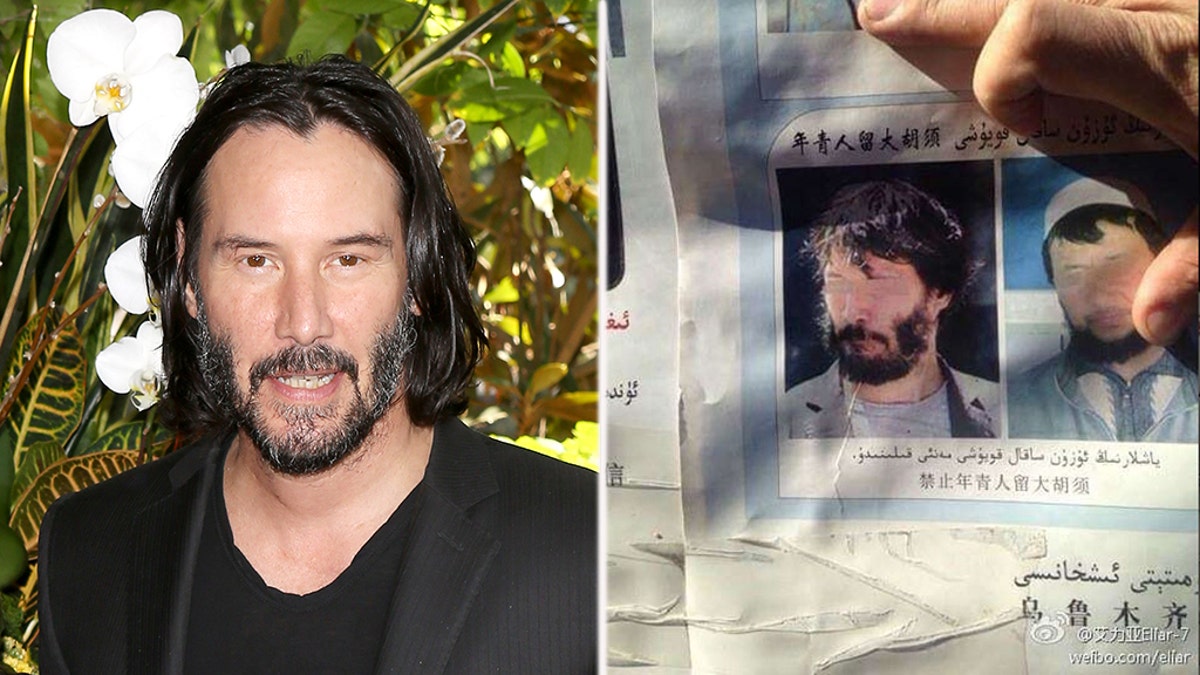

A picture of "Matrix" actor Keanu Reeves (left) appeared to be featured in Chinese government posters (right) (Getty (left image))

An untold number of Chinese Uighurs, estimated anywhere between one and 5.5 million, have disappeared into prisons and camps under Communist Party rule in the country’s autonomous Xinjiang region, according to activists and human rights groups, following a large-scale effort to purge and squash “Islamic terrorism” within the mostly Muslim ethnic minority.

And apparently even Hollywood star Keanu Reeves inadvertently played a role in the propaganda push.

A photo of what appears to be the “Matrix” and "John Wick" actor appeared on government posters a few years back, including the regional capital Urumqi city, with the headline “examples of religious extremism,” followed by “having a beard is forbidden for young people.”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Pictures of the poster have recently circulated in social media among those who follow the Uighur issue. Reeves’ spokesperson told Fox News the image in question is an unauthorized paparazzi shot and they have no control over its usage.

A local source told Fox News the public posters were once posted in both Mandarin and Uighur languages – although use of the latter has become increasingly prohibited. The Reeves poster is believed to be out of circulation now as many people displaying “examples for extremism” like having a beard or headscarf, have “disappeared.”

Even quitting smoking – a habit some Muslims avoid – can be viewed by authorities as an indication of “religious extremism," several sources have said. And the persecution of the Uighurs, most of whom are secular or practice a loose version of Sunni Islam, goes far beyond the mere banning of beards and dress.

One of those Uighurs is Mihrigul Tursun, now 29, who traveled to Egypt in 2013 to study. She married an Uighur in Egypt and gave birth to a healthy set of triplets – two boys and girl. But on arrival back in her homeland in May 2015, she was taken into custody at the airport by authorities and had her two-month-old babies taken from her, she said in a recent interview with Fox News.

COLOMBIA’S PEACE AGREEMENT BLOODIED BY DISTRUST, DRUGS - AND THE VENEZUELAN REGIME

“They questioned me nonstop for three days and nights, and then took me to even a more intense place for another seven days, and then to jail. They kept asking me about connections to terrorist groups I had never heard of,” said Tursun, who was granted a Parole Authorization Visa to the United States in 2018, and currently lives in the Fairfax, Virginia, area. “Then one day at the end of July, I was suddenly taken to the hospital and told that one of the babies – they only showed me from afar – was not doing great.”

Her son died the next day, she said. As for her surviving children, her son has a scar across his chin, and her daughter is deeply traumatized, Tursun said.

After her initial arrest, Tursun, who said she was arrested several more times, and claims to have been both physically and mentally tortured during interrogations, believes she was targeted by Chinese authorities for having lived in Egypt.

Mihrigul Tursun, now 29, traveled to Egypt to study. She later married and gave birth to triplets – one boy and girl – but on arrival back in her homeland in May 2015, was apprehended, her two-month-old babies taken from her. One died while she was in custody. (Mihrigul Tursun)

“They beat me up, one time so that my right ear was bleeding. They kept telling me I was lying and hiding information. I was made go on a special chair connected to electricity. They stripped me naked and shaved my head,” she recalled. “People were chased by dogs and bitten and given injections to numb them. I was losing my mind. But the treatment of the men was even worse.”

Tursun said she was detained for the last time in January 2018 – stuffed into an underground cell with dozens of other Uighur women. Her husband has since been imprisoned, and she has no idea of his whereabouts or condition. Nor can she reach her family.

“After I was released, my parents had already been taken to the camps,” she said. “I got just one nervous call where they asked me to say nothing about China and the government and told me only to say I love my country and they told me never to talk about my experience and never to come back.”

Mihrigul Tursun and her surviving children were given safe harbor in the United States

Although China’s constitution espouses freedom of religion, the government has endeavored for decades to cultivate a firm grip on the Xinjiang region, home to around 24 million, more than half of whom are Muslim ethnic Uighurs. The Uighur language and cultural identity are different from that of China, and many there have long resented what they call “Chinese occupation.”

Anti-government riots in the region in 2009 led to a crackdown. Another campaign came in 2014, when the government of President Xi Jinping clamped down. More recently, beginning in late 2016, Uighurs accused of bestowing “strong religious views,” or opinions considered counter to the Communist Party narrative, were swept up en masse without charge.

The Chinese have defended their actions in Xinjiang in an effort to snuff out what they call a Muslim extremist separatist movement. The Chinese have blamed a number of terrorist incidents on separatists, including a 2015 attack by long-knife-wielding assailants that left 39 people dead at a railway station in the Chinese city of Kunming. Another eight people were killed in an attack in February, 2017.

ANNUAL UN GATHERING A HOTBED FOR SPIES, MANY FROM US ADVERSARIES

Sainawar Rouzi, an anesthesiologist, described what she called the long-standing persecution of Uighurs in the medical profession, where she said Chinese doctors are given the coveted assignments. “I had my son, and when he was two-and-a-half years old, I took him to the pre-school because I had to work. He wasn’t looked after. They beat him. He was having nightmares. I didn’t want my son growing up under that regime,” said Rouzi, who now lives in Ohio and works as a nurse.

Rouzi said her family never practiced a religion, because “everyone was scared of the Communist Party,” and her only encounter with Islam growing up was watching her father prayer in secret after her mother died, and telling her that her mother “was in heaven.” Rouzi, 48, and her family fled to the U.S. in 2001 after her husband, also a doctor, was accused of “treating terrorists” for tending to other ill Uighurs.

“Even though I live here, my whole body is scarred from the government. I am inside the prison,” she said. “I cannot contact my family. I don’t like myself because for years I was silent. We grew up like this and yet we said nothing. But this is a genocide. I cannot be silent anymore.”

While some Uighurs are arrested and put behind bars, others are forced into what many in the international community are calling concentration camps. While accurate statistics are difficult to come by, it's widely estimated at least one million Uighurs have been sent to camps, with many more arbitrarily detained.

Abuduwaresi Abulimiti, a 33-year-old chef now in Boston, came to the United States from Xinjiang in late November 2016 and said he knows he cannot return home anytime soon.

Uighurs told Fox News of terrible conditions at the camps, which they charge don’t have enough proper food or medicine for those who fall ill. The ages of those inside range from around 14 to more than 80. They are said to mostly spend their time in indoctrination sessions – singing songs devoted to the Chinese Communist Party and listening to lectures – and have no access to the outside world.

Abuduwaresi Abulimiti, a 33-year-old chef now living in Boston, came to the United States from Xinjiang in late November 2016 and said he cannot return home anytime soon.

“They are genociding, killing our people. I hope the American people, the American government, can please pressure the Chinese government to shut down these concentration camps,” he said. “For China, religious people means terrorists. But that is only their lie to the world. They are really doing this because they want to brainwash, they want everyone to only believe in Communism.

Like most Uighurs in exile, Abulimiti has no contact with his family in his homeland. “Last time I talked with my parents was June 2017, and at that time my mom told me, ‘Do not try to contact us. Just live outside the country and do not come back',” he recalled.

Abulimiti also said he was very recently contacted by Chinese police via the messenger app WeChat and ordered to return to China. He said he was also cautioned against speaking to the media.

The official position of the Chinese government is that they are “winning the war against religious extremism and separatism,” and cite the decline of riots and deaths from terrorist attacks over the years as proof of their success.

As for the camps, the government vehemently denied their existence, until a September news report revealed satellite pictures of a vast expansion of facilities deemed “vocational and educational training centers” designed to “protect people and prevent the spread of extremism.” The following month, such camps were quietly legalized.

Chinese officials have testified before the United Nations that camp attendees were “happy to be shown how to inoculate themselves against religious extremism,” and they never “realized how rich and colorful life could be.” The Chinese government has also staunchly denied any accounts of torture, and insisted all those sent to facilities are respected, and called criticism of their approach by the likes of U.S. “political bias.”

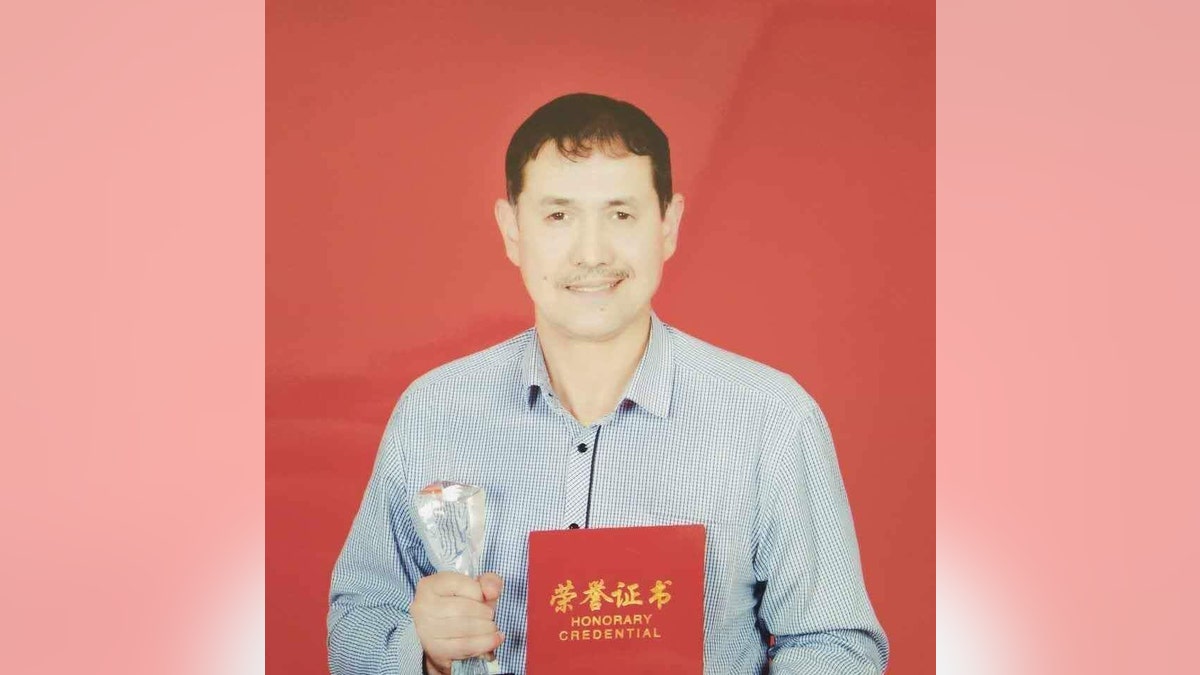

Alfred Erkin's father, believed to be held in a Uighur "concentration camp," or what the government refers to as a vocational and educational center

The United States and other Western nations have routinely expressed serious concerns for the Uighur population and demanded China cease the arbitrary detentions. China’s ambassador to the U.S., Cui Tiankai, responded to those calls in November, and threatened retaliation against the U.S if the Trump administration went ahead with sanctions for the alleged human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

But for those like Alfred Erkin, a 21-year-old Uighur in Virginia, the United States' history of standing up for the oppressed and for religious freedom, is the only hope they have.

“I came to the United States as a science major in 2015 to study and now I can’t go home," he said. "I had to drop out as I can’t work on a student visa. I can’t focus, my family has all just disappeared.”

Raised in what he described as a secular family, Alfred said he witnessed more and more prohibitions placed on Uighurs, from the banning of certain clothing, and the Uighur language in the classroom.

“For my whole life, I just kept silent. I didn’t participate in anything political, I did everything the government told me to do. I followed every single rule and yet still they detained my parents and 11 members of my family,” he said. “At first, the government denied the existence of the camps and then they said it was for vocational training. My mother spent decades as a mathematics teacher and my father was a television and producer. Why do they need job training?”