Opioid epidemic: Funeral director's view

Kevin Moran has been a funeral director for 33 years in Staten Island, New York. The opioid epidemic is weighing heavily on him as he's had to bury more and more young people in recent years

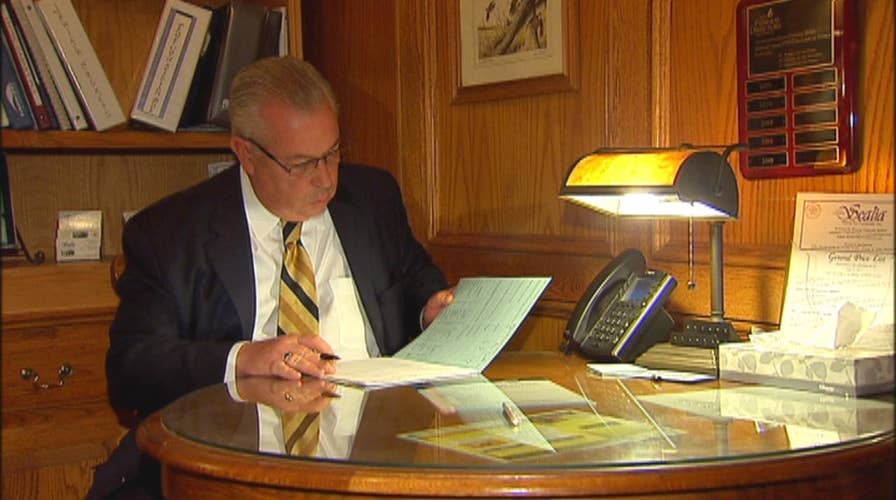

When Kevin Moran speaks to young people, he unscrolls about a dozen letter-size papers taped together and holds them squarely in front of their eyes.

They are death certificates of people their age who accidently overdosed on opioids, or consumed some from a tainted batch, and ended up at the funeral home he directs.

"Don’t do it!" Moran yelled out at the audience in one of his talks last year. "I don’t want to see you in my funeral home! I’m here for one reason, to scare the living crap out of you."

"If you want to come by the funeral home when I have a drug overdose case, I’ll bring you...I’ll show you what the person looks like and I’ll show you what the family goes through, and you watch it, then tell you me you want to do it.”

Kevin Moran, a funeral director on Staten Island, shows students a list of death certificates of young people whose bodies have been brought into his funeral home. (AddictionAngel)

The toll of the opioid addiction epidemic that has gripped communities across the United States began making itself felt in Staten Island about three years ago, when the bodies of people barely old enough to drive or buy a beer began appearing in larger and larger numbers at the John Vincent Scalia Home for Funerals in this New York City borough, where many residents work in public service jobs.

In 2014, the casualties of opioid addiction at the funeral home began appearing at a rate of one every four to six weeks. Every one of Staten Island’s 13 funeral homes had a similar experience. Last year, accidental overdoses in Staten Island accounted for the deaths of more than 100 people, a jump of 35 percent over 2015, according to health officials.

Nationwide, 52,404 people died from a drug overdose, up from 47,055 in 2014, according to the Centers for Disease Control. A majority, 63 percent, of the deaths involved opioids.

Even for Moran, a veteran in an emotionally arduous business that requires extraordinary mettle, the steady stream of so many lives cut short was too much to bear.

It's a father missing the opportunity to walk his daughter down the aisle, a graduation. They are avoidable deaths.

“I’m a parent, and when I see another parent hurting over a death like this, it tears me apart,” Moran says, eyes downcast. "The very fabric of me is just torn apart."

Wakes for people who have lived a long life are filled with mourners reflecting on memories of special occasions, of the deceased person's milestones. But at these wakes for younger people, the thoughts are about what could have been.

"It's a father missing the opportunity to walk his daughter down the aisle, a graduation that didn't happen," Moran says. “The world is not designed … for parents to bury their children. They don’t have to happen. They are avoidable deaths.”

Moran decided he could not just watch as the victims of the epidemic were carried one after another into the John Vincent Scalia Home for Funerals. He would make the last chapter – the avoidable chapter – real for those who could still be saved from the same fate. Moran became an activist, speaking to groups, especially young adults, about the dangers of opioids and the devastation it brings to those they love.

Pills and bottles (VladimirSorokin)

Part of his effort includes speaking on a regular basis at opioid addiction support meetings organized by a Staten Island nurse, Alicia Reddy, who founded a program called Addiction Angel.

Hundreds attend. They listen to recovering addicts as well as relatives of people who died of accidental overdoses.

That is one of the places where Moran takes the pile of death certificates to drive home the point about where the dangerous path of opioid addiction often ends.

When you lose a child to a drug overdose...the emotions that are churned up are unlike any other.

“Instead of holding the high school diploma for their child, parents are being given their death certificates,” Moran says, his face pained. “We do things when we are 17 or 18 without any reservations or fears. We think we are immune.”

And so he'll do whatever it takes to lull people out of their complacency, their denial -- whether that means describing in detail the young mother who overdosed and was found dead with the needle still in her arm and her newborn baby on her chest. Or whether he has to tell them about the people whose names are on the death certificates he holds -- the coach, the lawyer, the accountant, the mother, the father.

"When Kevin speaks, it's impactful," Reddy says. "He's been in schools and some kids will be seated in the back, talking to each other and he'll scream at them" to listen.

Moran has no qualms about taking his warning to people he sees abusing drugs. He says, in bewilderment, that he’s even seen the drugs being taken in the parking lot of the funeral home, by friends and acquaintances attending the wake of someone who has died from an accidental overdose.

“The drug epidemic is so different than any other,” Moran says in an interview with Fox News. “When you lose a child to a drug overdose, the heroin or the pills, the emotions that are churned up are unlike any other.”

“Most of the children who have passed started after being in a car accident, or getting a sport injury, and were prescribed painkillers by a doctor” and got hooked, Moran says.

He knows that when properly taken, opioids make a life-changing difference for people who suffer debilitating and chronic pain.

“Percocet can be a blessing when you’re in pain,” Moran says.

But there is no escaping the connection he makes between opioids and the young bodies that have filled funeral homes and cemeteries in the borough. And so Moran, who has six herniated disks, said he refuses to take painkillers for relief.

Percocet can be a blessing when you're in pain.

The toll of the epidemic has claimed people known to Moran – the children of friends and acquaintances, and even of a part-time employee.

“His son passed away on a Friday night in his friend’s apartment,” Moran says of his employee. The substance of the drug he consumed was so potent, he said, that it quickly decomposed his body, making it impossible to prepare the body for a funeral or burial.

“I had to call the father, my employee, and tell him that it was undoable,” he says.

His adult daughters, who are millennials, are healthy and thriving.

“I’m very lucky that they’re OK,” Moran says.

But he will not allow himself to take comfort.

“That could all change tomorrow,” he says.

“Most of the people that are victims of this scourge are really good decent kids who come from decent families,” Moran says. “Their father could be a police officer, their father could be a fireman, their mother could be a nurse or school teacher.”

“It could be the wealthiest kid and the poorest kid, and the drugs don't care.”