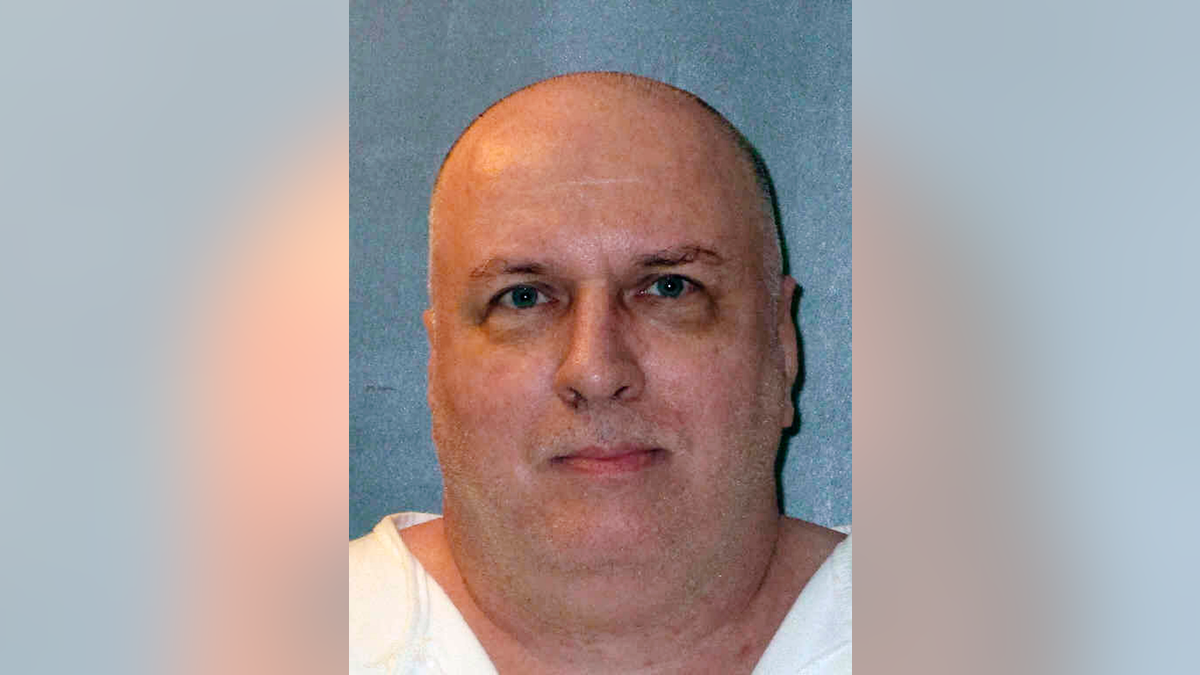

This undated photo provided by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice shows Patrick Murphy. Texas death row inmate Patrick Murphy and Alabama death row inmate Dominique Ray both came to the Supreme Court recently with the same request. Halt my execution, each said, because the state won’t let my spiritual adviser accompany me into the execution chamber, even as other inmates of different faiths get that ability. But while the Supreme Court declined to stop Ray’s execution in February, they gave Murphy a temporary reprieve Thursday night. The difference in the two cases looks like it comes down to when each man asked for his spiritual adviser to be present. (Texas Department of Criminal Justice via AP)

DALLAS – Texas prisons will no longer allow clergy in the death chamber after the U.S. Supreme Court blocked the scheduled execution of a man who argued his religious freedom would be violated if his Buddhist spiritual adviser couldn't accompany him.

Effective immediately, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice will only permit prison security staff into the execution chamber, a spokesman said Wednesday. The policy change comes in response to the high court's ruling staying the execution of Patrick Murphy, a member of the "Texas 7" gang of escaped prisoners.

Texas previously allowed state-employed clergy to accompany inmates into the room where they'd be executed, but its prison staff included only Christian and Muslim clerics.

In light of this policy, the Supreme Court ruled Thursday that Texas couldn't move forward with Murphy's punishment unless his Buddhist adviser or another Buddhist reverend of the state's choosing accompanied him.

One of Murphy's lawyers, David Dow, said the policy change does not address their full legal argument and mistakes the main thrust of the court's decision.

"Their arbitrary and, at least for now, hostile response to all religion reveals a real need for close judicial oversight of the execution protocol," Dow said

Murphy's attorneys told the high court that executing him without his spiritual adviser in the room would violate the First Amendment right to freedom of religion. The 57-year-old — who was among a group of inmates who escaped from a Texas prison in 2000 and then committed numerous robberies, including one where a police officer was fatally shot — became a Buddhist while in prison nearly a decade ago.

In his concurring opinion, the court's newest justice, Brett Kavanaugh, wrote that Texas had two options going forward: allow all inmates to have a religious adviser of their religion in the execution room, or allow religious advisers only in the viewing room, not the execution room.

"The government may not discriminate against religion generally or against particular religious denominations," Kavanaugh wrote.

Kristin Houlé, executive director of the Texas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, called the new policy "cruel and unusual," and urged the department to reconsider.

Prison chaplains will still be able to observe executions from a witness room and meet with inmates on death row beforehand, said Texas Department of Criminal Justice spokesman Jeremy Desel. He declined to elaborate on the reasoning behind the policy change.

The change brings Texas in line with most other death penalty states, which do not allow clergy into the execution chamber, according to Robert Dunham, a lawyer and executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center. But it is also likely to open new legal fights for America's busiest execution state, he said.

The policy change could be challenged as generally discriminating against religion and as retroactively targeting Murphy despite having a general formulation, Dunham said. If these arguments are presented to the high court, a ruling could have implications for how executions are conducted around the country, he said.

The Supreme Court's decision in Murphy's case followed a similar appeal in February, when the court ruled Alabama could execute a Muslim inmate without his Islamic spiritual adviser present in the execution chamber. The court decision that allowed Dominique Ray to be executed attracted public criticism , and Dunham said the ruling staying Murphy's execution might have been an effort by the justices to avoid further blowback.

"When you look at the court's order, they were hoping that Texas would give them a way out by accommodating Patrick Murphy's request," he said. "Texas has chosen not to do that, so it's likely that the ball with be back in the proverbial judicial court."