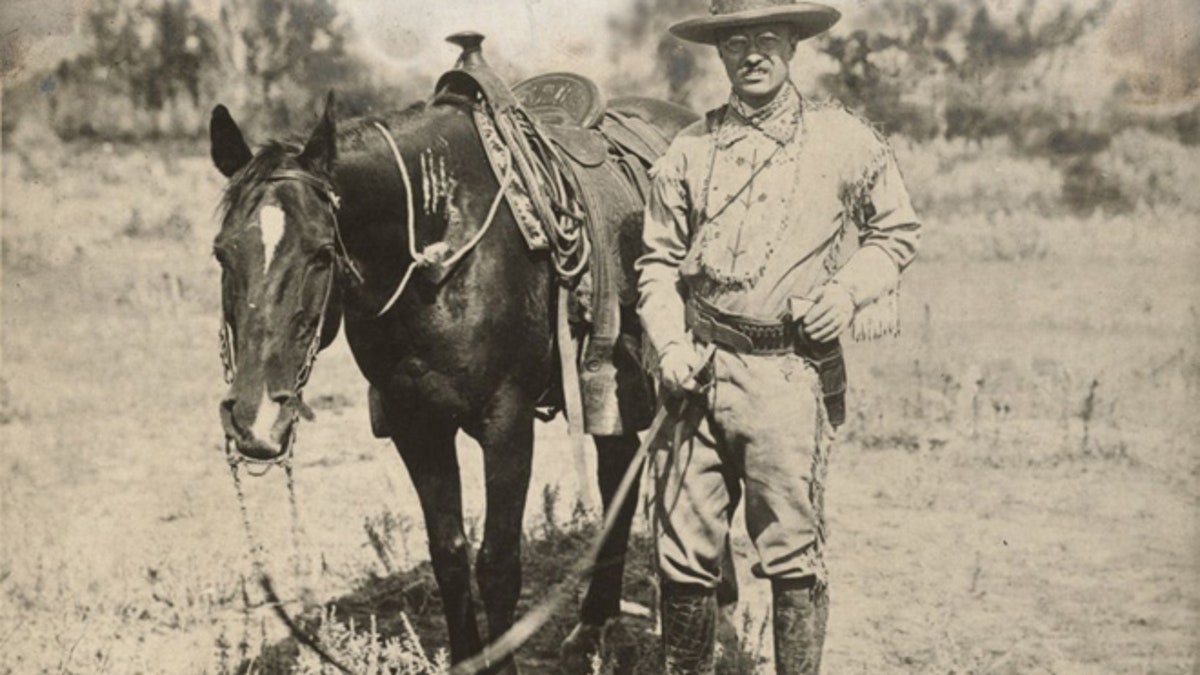

Teddy Roosevelt fell in love with the Badlands during a hunting trip in the 1880s, according to historians.

In the Badlands of North Dakota, on the banks of the bubbling Little Missouri River, the fabled former ranch of Teddy Roosevelt has become a battlefield in the fight between industry and the conservationists who view the 26th president as their patron saint.

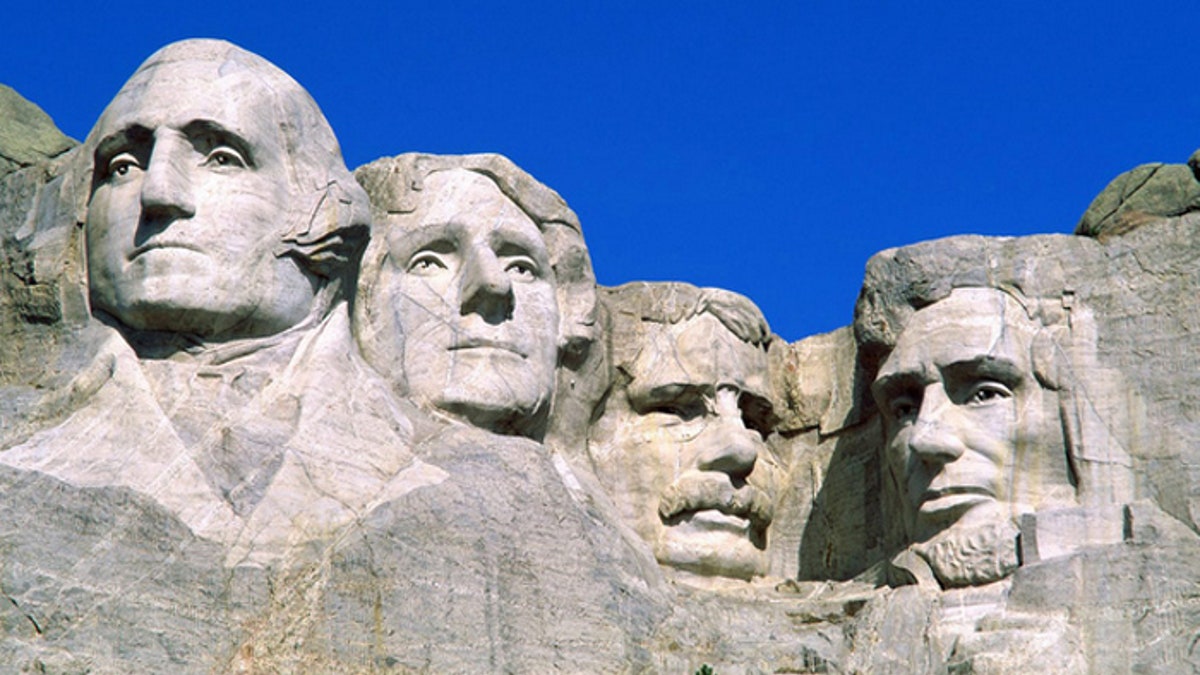

Hunters and environmentalists fear the main, 218-acre section of the 25,000-acre Elkhorn Ranch, which once belonged to the man whose passion for conservation changed the nation and helped land his face on nearby Mount Rushmore, could be forever marred by a mining project now under way on adjacent land. The opponents appear to be out of options, but still hope the rugged land that helped shape TR’s wilderness affection can be spared.

“He spent considerable time among the cowboys and ranchers and others in the West, and that gave him an entirely different perspective on what America is all about,” Roosevelt’s great-grandson Tweed Roosevelt told FoxNews.com. “It knocked out of him the East Coast snobbery and elitism approach that he had as a young man and turned him into a much more human person.”

“There is a lot of gravel to mine. I will keep on mining year after year, for years to come, and will not stop until I get all the gravel."

The controversial gravel mining project could eventually span hundreds, if not thousands of acres, bordering the ranch, which became a western refuge for the bespectacled man who grew from sickly child to Harvard-educated war hero and symbol for American machismo.

Teddy Roosevelt was immortalized on Mount Rushmore in South Dakota, 260 miles south of his fabled ranch.

The National Park Service purchased 5,200 acres, including the ranch, in 2007 as part of the Theodore Roosevelt National Park. The $5.3 million acquisition was aided by the Boone and Crockett Club, the venerable conservation organization founded by Roosevelt in 1887.

However, the government did not secure the mineral rights for the property, the majority of which were subsequently acquired by the Montana-based Elkhorn Minerals.

While the site where Roosevelt’s riverbank log cabin once stood lies within Theodore Roosevelt National Park and can’t be developed, the surrounding lands, under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service, are not similarly protected.

Roosevelt's ranch sat on the banks of the Little Missouri River. (TheodoreRooseveltCenter.org)

Roger Lothspeich, owner of Elkhorn Minerals, told FoxNews.com that despite opposition, he has no plans to stop the mining project, which began last month.

“There is a lot of gravel to mine,” he said. “I will keep on mining year after year, for years to come, and will not stop until I get all the gravel. That’s the type of individual I am. I just don’t give up.”

Lothspeich said he was willing to exchange land with the Forest

Service if there was a comparable place to mine nearby, but Forest Service officials said in a statement "a reasonable option could not be found."

Environmentalists and historians still hold out hope the project can be halted by the courts. The National Parks Conservation Association, represented by the Chicago-based public interest law firm, Environmental Law and Policy Center, took its case to federal court in Washington, D.C., on Friday seeking a preliminary injunction stopping the U.S. Forest Service from allowing the mining project to go forward.

(Tweed Roosevelt, (l.), believes he's fighting the same fight his great-grandfather fought. (TheodoreRooseveltCenter.org))

The Center argued that the National Park Service violated the National Environmental Policy Act in its approval of the environmental assessment. The judge’s ruling is pending.

Deemed one of the “11 most endangered historic places” in the nation by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the Elkhorn Ranch is prized by conservationists and environmentalists because between 1884 and 1887, Theodore Roosevelt hunted, bred cattle and explored the lands there, and more importantly, began his writings on conservation. While project won’t be on the Roosevelt ranch, opponents said the mining and its infrastructure will be a noise and visual blight at the important historic site.

“Unfortunately, the serenity of the ranch, which lies on both sides of the Little Missouri River, is threatened by a proposed new road that would introduce a visual disruption, as well as traffic, noise and dust,” the National Trust for Historic Preservation said in a statement.

Tweed Roosevelt, the great-grandson of the former president, said the ranch was the inspiration for the former president who ordered 230 million acres under federal conservation -- including the Grand Canyon -- during his two-term presidency that began in 1901.

Roosevelt was just 26 when he established the ranch in 1884. While he would go on to serve as New York City’s police commissioner and governor of the Empire State, Tweed Roosevelt said his Badlands getaway helped him establish a national presence and perspective that led to even bigger things.

Roosevelt had come to the Badlands in September 1883 to hunt buffalo. By the end of his 15-day hunting trip, he had bought Chimney Butte Ranch, some 35 miles from the future Elkhorn site. Five months later, after his wife and his mother died on the same day, a grief-stricken Roosevelt decided to leave the East and increase his interests in the cattle business. He added to his holdings by buying rights to the land that would become Elkhorn for $400.

Roosevelt’s time in the Wild West helped him heal from family tragedy and develop the persona America came to embrace, he said.

“This was an extremely important period in TR’s life,” Tweed Roosevelt told FoxNews.com.

“And also incidentally, politically gave him a national base which later on, helped him quite considerably get to The White House,” Tweed Roosevelt said. “For our family, it was very important because it turned him into who he was publicly, but also the kind of father and grandfather and family man he was.”

In describing the land, the former president wrote in a 1913 autobiography: "It was a land of vast silent spaces, of lonely rivers, and of plains where the wild game stared at the passing horseman… In that land we led a free and hardy life…."

The land, nicknamed the “Cradle of Conservation,” is an iconic place in America’s cultural heritage worth preserving that inspired Ideals worth perpetuating, Tweed Roosevelt said. His organization credits “Elkhorn’s silent grandeur” with sparking America’s conservation movement.

Under federal law, the National Park Service said it is required to “provide access to allow the owner of private minerals to remove their minerals.” Under their agreement, once the gravel is extracted from a 5-acre parcel, the area must be “reclaimed” or restored, before the company can move to the next 5-acre parcel.

Besides legal action, President Obama or Congress could designate the area a national monument. The President would rely on the Antiquities Act, established by none other than Roosevelt.

Despite the pending legal challenge, and possible government intervention, Lothspeich said he is on the right side of the law.

“I have the right to mine my gravel. It’s legal. It’s constitutional.”