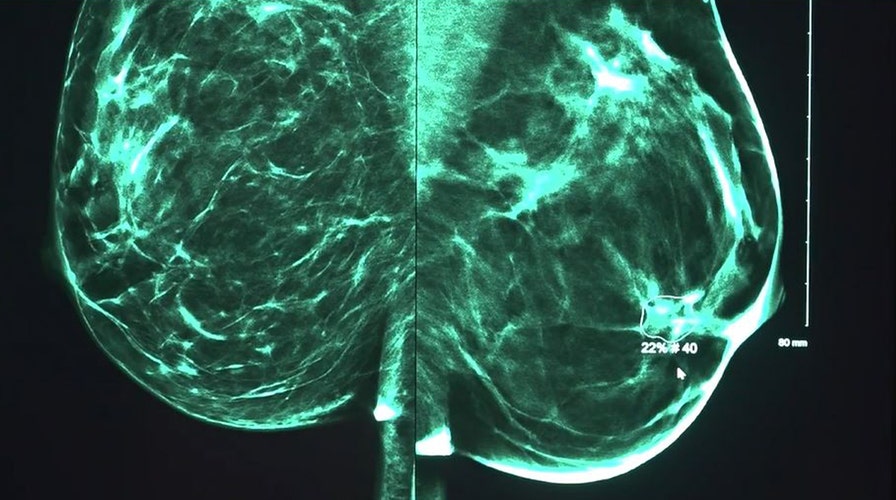

Artificial Intelligence detecting cancer in some U.S. hospitals

Doctors believe artificial intelligence is now saving lives, after a major advancement in breast cancer screenings. AI is detecting early signs of the disease, in some cases years before doctors would find the cancer on a traditional scan.

This story discusses suicide. If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, please contact the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

A new documentary highlights the story of a 10-year-old girl who was admitted to a Florida children's hospital for severe pain and then promptly removed from the custody of her parents after staff accused them of "medical abuse."

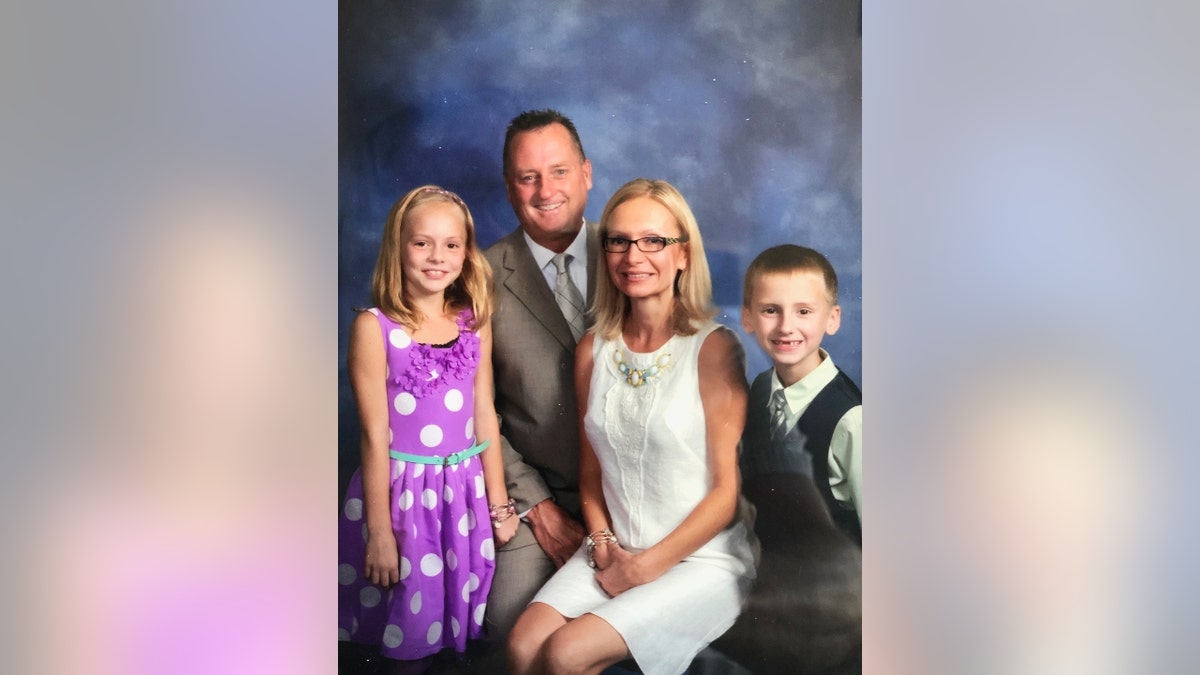

Netflix's "Take Care of Maya" follows the story of Maya Kowalski and her mother, Beata Kowalski, a registered nurse, as they navigate Maya's rare, chronic neurological condition called complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) – a poorly understood affliction that causes severe pain throughout a person's body due to nervous system dysfunction, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

"We, as parents, try to do the best we can for our children," Jack Kowalski, Maya's father and Beata's husband, says in the documentary. "You do everything for them. That's what Beata and I did. But there's nothing that could have prepared me for what I went through with my family. Nothing."

Dr. Anthony Kirkpatrick, who specializes in pain relief, initially diagnosed Maya with CRPS when she was 9 years old and helped her get treatment for the illness, which included doses of ketamine to help dull her pain. The treatment worked for a while, until she relapsed at age 10 in 2016.

Netflix's "Take Care of Maya" follows the story of Maya Kowalski and her mother, Beata Kowalski, a registered nurse, as they navigate Maya's rare, chronic neurological condition called complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). (Netflix/"Take Care of Maya")

She was admitted to Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital (JHAC) in St. Petersburg, Florida, after the relapse. Her symptoms included "episodes" of severe pain on her limbs and skin lesions. Her feet would also turn inward when she was experiencing CRPS episodes – a common reflex for patients experiencing pain from CRPS.

Her mother, who took meticulous notes regarding Maya's illness due to her experience as an R.N., insisted with doctors and nurses at the children's hospital that Maya had been diagnosed and CRPS, and doses of ketamine help with her pain.

Hospital staff interpreted her insistence as hostility and did not believe everything she said about her daughter's condition.

As Beata demanded staff allow Maya to take ketamine to ease her pain, Dr. Sally Smith, medical director of the Pinellas County child protection team, intervened and accused Beata of medically abusing her daughter – an accusation the hospital still stands by after a Sarasota County court determined that staff had reasonable cause to suspect abuse.

Dr. Anthony Kirkpatrick, who specializes in pain relief, initially diagnosed Maya with CRPS when she was 9 years old and helped her get treatment for the illness, which included doses of ketamine to help dull her pain. (Netflix/"Take Care of Maya")

Doctors called the Florida Department of Children and Families (DCF) to report their suspicions of medical abuse. Maya was put into the custody of child protective services worker Catherine Bedy at the hospital, where she remained for months without seeing her parents.

"[W]hen Beata arrived and told them about Maya's medical history, including multiple visits to different specialists to diagnose her CRPS, and ultimately that ketamine infusions were the only thing that worked, instead of checking out her story, they became offended at her directness and certainty," attorney Greg Anderson explained. "None of them had any expertise in pain management, CRPS or ketamine treatments."

He added that Smith "determined that because Maya had been treated by a number of physicians before being properly diagnosed and because [Smith] disagreed with the ketamine infusions as a treatment," her mother Beata was exhibiting signs of "Munchausen by proxy."

Maya Kowalski's mother, Beata Kowalski, was accused of Munchausen by proxy after explaining her daughter's CRPS and treatment to hospital staff. (Netflix/"Take Care of Maya")

Munchausen by proxy is a psychological disorder in which an abusive parent or caretaker makes up or causes an illness for an individual in their care who is not actually ill. People impacted by the disorder seek attention and sympathy, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

Smith allegedly ignored communications from Kirkpatrick, who attempted to explain Maya's CRPS and ketamine treatment to JHAC staff.

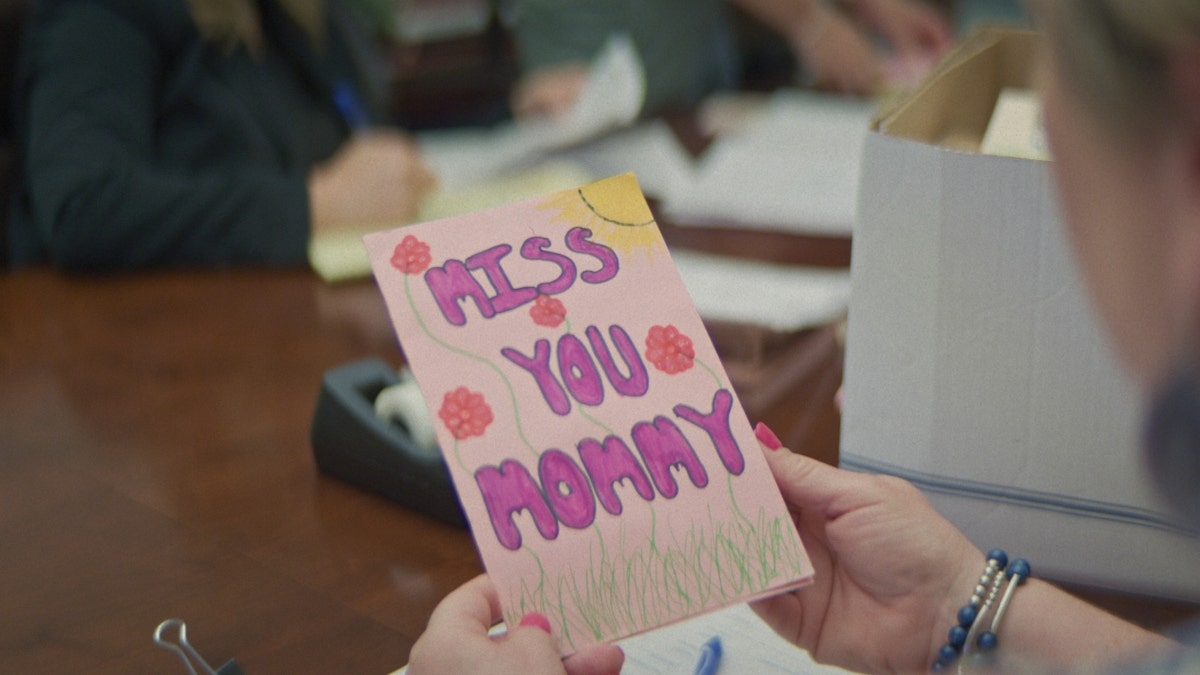

A legal battle ensued as Maya remained in DCF custody while she continued treatment at JHAC. In the documentary, Maya says she did not experience much improvement in her condition during her time at the hospital.

"Maya was kept in custody for three and a half months, isolated from her family, her friends, her attorney and even her [p]riest," Anderson said. "Johns Hopkins told the court that Beata was a danger to her daughter and shouldn’t even be allowed to talk to Maya unless supervised by a Johns Hopkins social worker and then only once a week. Eventually, she had no contact with her daughter."

JHAC told Fox News Digital in a statement that the hospital's priority is "always the safety and privacy" of its "patients and their families."

"Therefore, we follow federal privacy laws that limit the amount of information we can release regarding any particular case. Our first responsibility is always to the child brought to us for care, and we are legally obligated to notify [DCF] when we detect signs of possible abuse or neglect," the hospital said. "It is DCF that investigates the situation and makes the ultimate decision about what course of action is in the best interest of the child."

A legal battle ensued, at which point DCF took custody of Maya as she continued treatment at Johns Hopkins without much improvement, as Maya explains in the documentary. (Netflix/"Take Care of Maya")

A motion to obtain immunity from the hospital states that Beata Kowalski once stated that Maya was in so much pain, she "wants to go to Heaven." Another time, Beata allegedly said she "may as well consult hospice so she can finally get enough medication and just let her die because she doesn't deserve to live this way," the motion states.

Doctors who consulted with Beata and Maya prior to her time at JHAC also accused Beata of medical abuse, according to the motion. In 2015, Dr. Elvin Mendez wrote that Maya's illness was "all being driven by the mother." Also in 2015, doctors at Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago flagged "abuse behavior" from Beata.

An investigation revealed that Beata filled out fraudulent prescriptions for her daughter's medication and administered them to Maya through a port at home, according to the motion.

The hospital also alleged that Maya's demeanor would change when her mother entered her hospital room. In an interview between police and Maya's father, Jack Kowalski, Jack agreed that part of Maya's condition appeared to be psychological, a transcript from the interview shows.

Beata Kowalski, Maya Kowalski's mother, died by suicide on Jan. 7, 2016, after hospital staff accused her of medically abusing her daughter. (Netflix/'Take Care of Maya')

Doctors and detectives frequently returned to the fact that Maya would, at times, appear to be acting like a normal child without pain, and then the pain would come on suddenly when she was asked about it or when her parents were present. Maya said in the documentary, however, that her pain would come and go in waves, as is normal for people experiencing CRPS.

After Johns Hopkins delayed legal procedures in Maya's case, Beata hung herself in the garage on Jan. 7, 2016, "to free her daughter," Anderson said.

"Maya was dying under Johns Hopkins mismanagement and terrible care."

Following Beata's suicide, two doctors assigned to Maya's care exchanged the following messages, obtained by Netflix, with each other:

Doctor No. 1: "Learned today ketamine girl’s mom committed suicide yesterday. Sorry to say my prediction was correct."

Doctor No. 2: "OMG…this is terrible. I know we did the right thing, but this is really f---ed up. I feel bad."

Doctor. No. 1: "I had another mother do this same thing. We definitely did the right thing for the child."

The Kowalskis are suing Johns Hopkins and Bedy, arguing that they "abducted, incarcerated and abused" Maya when she was 10.

"Do not trust the system."

The Sarasota County lawsuit mentions an incident that is also discussed in the film when Bedy stripped Maya of her clothing down to her underwear and then took photos of her without permission from her parents. Bedy said in court that the photos were taken for legal purposes, as seen in the doumentary.

Smith and her employer, Suncoast Advocacy Services, were initially named in the lawsuit but settled with the Kowalskis for $2.5 million. She has since retired, according to The Cut.

Maya Kowalski was separated from her parents for months after hospital staff accused her mother of Munchausen by proxy. (Netflix/'Take Care of Maya')

Anderson said parents need to protect themselves and keep copies of all their children's medical records as they are created.

"If your child has a complex illness, be very careful in ERs and anywhere you don’t have a relationship with the doctors," he said. "Do not trust the system. You don’t need to be paranoid, but the first time you get a feeling the doctor may not have your child’s interest at heart, or that they are acting strangely in their questioning and examination, ask direct questions of why they are there and who they work for."

"Sally Smith was famous for impersonating a treating physician, with a Johns Hopkins lab coat and an act that was designed to lure unsuspecting parents into divulging what the parents thought were innocent facts and history about their child, but Smith had… verbal traps," he continued.

Anderson said parents need to protect themselves and keep copies of all their children's medical records as they are created. (Netflix/'Take Care of Maya')

The end of the documentary features interviews with multiple other parents accused of medically abusing their children – some of whom were jailed for the alleged crime while most others agreed to a "case plan," which is essentially an agreement parents make with hospitals to get their children back in their custody.

"Parents who have children with… complicated medical conditions, and some who have had their own experiences in the child welfare system are reaching out and saying that 'Take Care of Maya' is giving them the will to keep fighting for their children and families," producer Caitlin Keating told Fox News Digital. "They have now found the courage to speak out and tell their personal stories on social media. We hoped that this film would spark a larger conversation and we see it doing just that."

One woman told Keating that "Take Care of Maya" shows families "aren't alone," and it gives them "hope that life can go on and it can get better."

"Thank you for being the voice for so many families that have been forced silent," the woman wrote.

Trial proceedings in the Kowalskis' case against Johns Hopkins and Bedy have been pushed to Sept. 11.