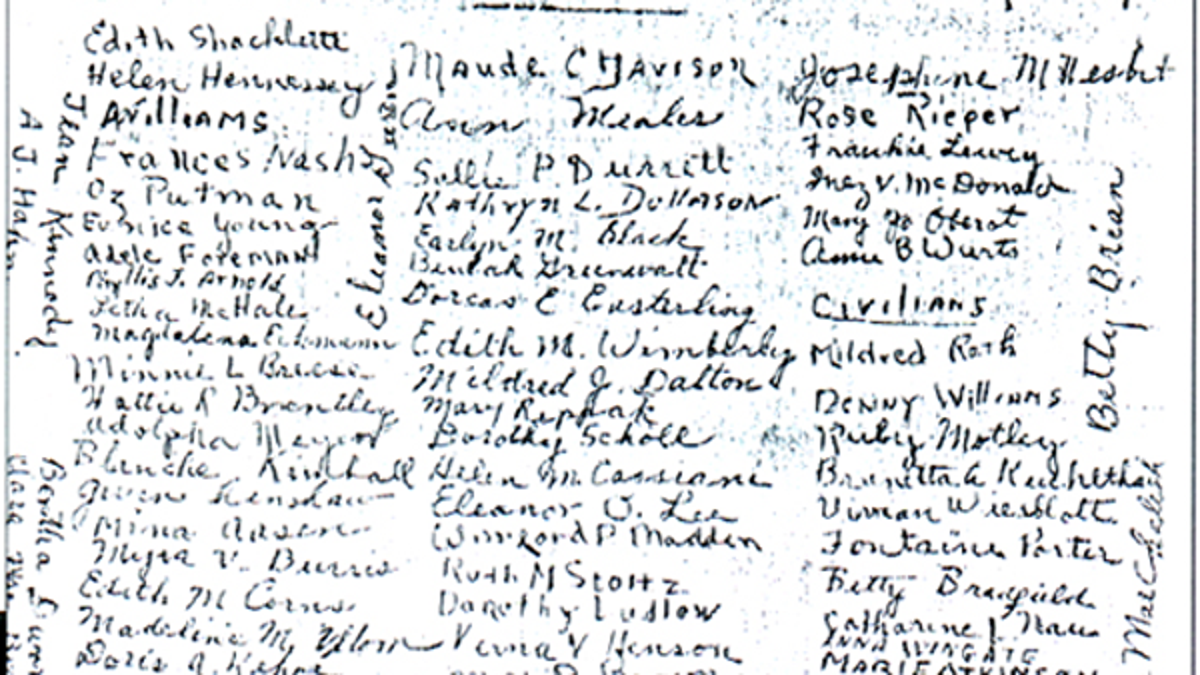

Known as the “Angels of Bataan and Corregidor,” the group of army nurse continues to hold the distinction of not losing a single member during their three years in internment.

One of World War II’s greatest untold stories began on April 8, 1942 when Lt. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright, the commander of the U.S. Army in the Philippines, ordered the evacuation of military and civilian nurses to the island of Corregidor. A month later, Corregidor fell and 77 American nurses were captured by the Japanese, becoming the largest group of female prisoners of war.

Known as the “Angels of Bataan and Corregidor,” the group continues to hold the distinction of not losing a single member during their three years in the Santo Tomas Internment camp.

“It is not that they were some of the first women POWs that made them special, but that they were average American from average towns and they survived in a horrific environment while never losing their commitment to serving their patients,” says Bernice Fischer, granddaughter of U.S. Army nurse Mary Bernice Brown-Menzie.

Fischer tells Fox News her grandmother entered the prison camp in 1942 weighing 130 pounds but had dropped to 75 pounds when she was liberated in February 1945.

Many of the women sought assignment in the Philippines prior to December 1941 when the Pacific was relatively peaceful and where they enjoyed dances and other luxuries.

But that changed after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and then launched an invasion of the Philippines. For months the nurses faced constant attack by Japanese planes, deteriorating conditions and dwindling rations.

Mary Bernice Brown

“There were 77 American women who became POWs and there were 77 who walked out in 1945. This is unprecedented, particularly for women who had no formal survival training,” says Elizabeth M. Norman, who chronicled the nurses in the book, “We Band of Angels: The Untold Story of American Nurses Trapped on Bataan.”

According to Norman, under the informal leadership of World War I veteran nurse Capt. Maude Davison, the women always kept to strict schedules waking every day and dressing in uniforms they fashioned themselves.

The discipline combined with a singular dedication to care for their patients, some of whom had been among the 75,000 American and Filipino soldiers captured on April 9, 1942 and forced on a 68-mile “death march” in 100-degree temperatures without food or water.

The nurses cared for the men, known as “The Battling Bastards of Bataan,” despite suffering from starvation and other diseases themselves.

Fischer tells Fox News her grandmother and the other nurses never thought of themselves as heroic because they saw their patients as the real heroes.

Many of the nurses kept diaries, which document the emotional trauma they endured as they witnessed the torture by their Japanese captors.

In one entry, Bernice’s grandmother writes about a soldier who was bound and tied up outside in the heat for three days before being shot in the back.

“Whether he died instantly or wounded and bleeding lived on until he finally died, we will never know. But this cruel, heartless and brutal treatment filled us all with deep grief and sorrow,” she wrote.

Adelaida Garcia

A gritty refusal to give in and a commitment to care was life-sustaining for nurses, says Lt. Col. Nancy Cantrell, an historian with the Army Nurse Corps,

“They were a tough bunch,” Cantrell added. “They had a mission. They were surviving for the boys … and each other. That does give you a bit of added strength,” Cantrell told Soldiers Magazine.

Despite the experience, some of the women carried on after the war without any bitterness.

“I have never been bitter, and I have always known that if I could survive that, I could survive anything,” Mildred Dalton Manning, who died in March 2013 at the age of 98, told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Norman believes those Angels she interviewed for the book recognized that there was little time to get their stories out.

“The women told me that not a day went by that they did not think about it, but didn’t speak about it,” Norman tells Fox News.

“Some of the women remained in the military,but even the military never asked these women. It was like they did not exist. By the time I spoke with them, they were in their 80s and realized that if they did not tell their story, no one would. They were not seeking recognition, but they wanted their experiences preserved,” adds Norman, who is a professor at New York University.

Another reason they spoke was to clear up myths, such as suggestions they had been raped.They also wanted to clear up facts that had been romanticized in such movies as "So Proudly We Hail" (1942), and "They Were Expendable" (1945).

“These women never sought recognition. They never took to the spotlight. It was the men they served with who actually sough to gain recognition of these women after the war,” says Fischer.