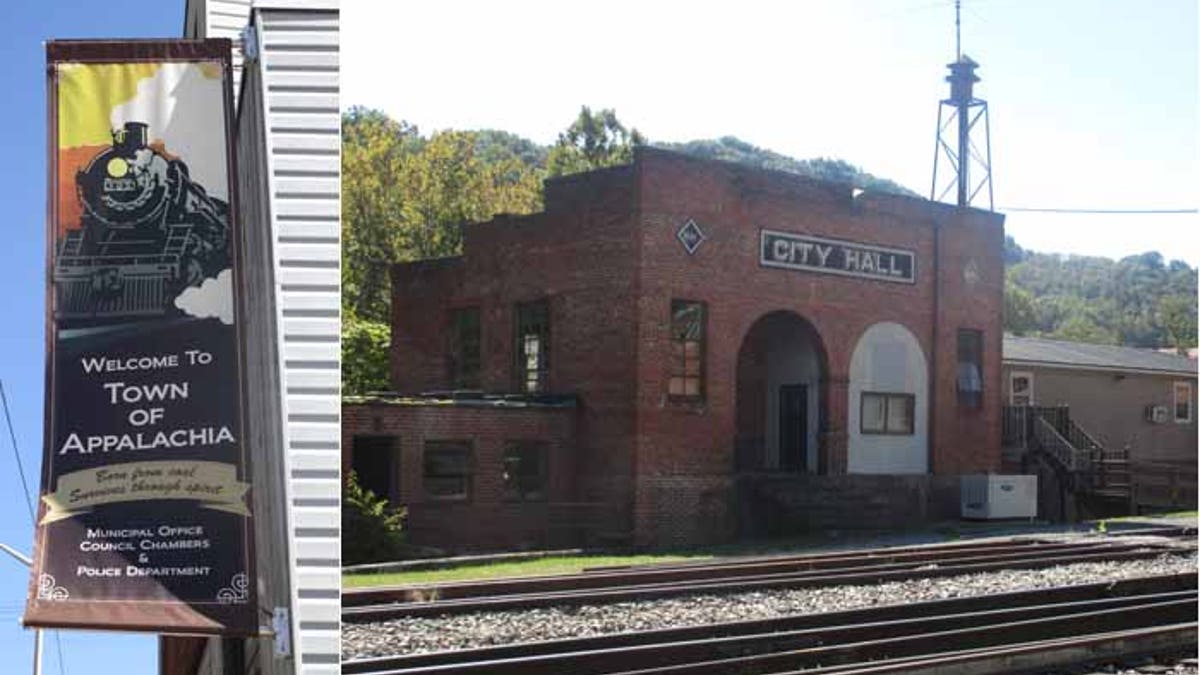

Appalachia, Va., boasts that it was "built from coal," but now its lifeblood has run dry. (FoxNews.com)

APPALACHIA, Va. – Roger Whited doesn’t have to think back too far to remember when Main Street was alive with bustling shops and offices, teeming sidewalks and even traffic jams, all thanks to the industry that was the lifeblood of this tiny mountain town and countless others like it.

But six years into what many term the Obama administration’s “War on Coal,” Appalachia’s main thoroughfare is a tableau of boarded-up buildings, empty storefronts and dilapidated homes. Those who still mill about on streetcorners are looking for jobs, not places to spend their paychecks.

"I remember when the downtown area was more vibrant -- streets were packed and businesses were open,” said Whited, who teaches high school social studies in Wise County. “There was the hotel and Bessie's Diner, which was a popular place to get a meal. There were several other restaurants, but now the only place that serves food is a gas station.”

[pullquote]

For generations, coal powered not only Appalachia’s homes and the lights on Main Street, but also the local economy. The salaries paid by companies like Cumberland River Coal Co. were enough to afford the trappings of a middle class, if hard-won, lifestyle. Men and women who toiled in the mines spent their money downtown and sent their kids to the local schools.

But the Obama administration’s tough regulations on coal-fired electric plants, combined with other market forces, have left the future of coal – and the people, companies and towns that depend on it – in doubt. The administration is seeking to reduce carbon emissions at coal-fired plants by 30 percent by 2030, a goal that industry officials call unrealistic. New plants are too expensive to build, and older ones are too costly to retrofit, they say.

[image]

"If somebody wants to build a coal-powered plant, they can,” President Obama said in January 2009, shortly after taking office. “It's just that it will bankrupt them because they're going to be charged a huge sum for all that greenhouse gas that's being emitted.”

Even as the nation endured a recession, followed by years of sluggish economic growth, coal towns like Appalachia reeled from policies dictated in Washington. As coal-fired plants closed, demand for coal plummeted. In 2011, Appalachia’s lone high school closed, a casualty of low enrollment.

In July, Arch Coal, parent company of Cumberland River Coal Co., announced plans to idle its mine in Appalachia and lay off 213 workers, a devastating final blow to the town of 1,800. That followed a similar move by A&G Coal Co., once one of the region’s biggest employers.

[image]

Miners who hung onto their jobs know their paychecks are numbered.

“You wake up every day wondering if you’ll have a job the next day,” Brandon Lawson, of nearby Big Stone Gap and a miner for six years, told the Bristol Herald Courier. “I’ve seen it [the decline of the industry] coming a long time ago.”

Tucked away in the mountains from which it takes its name, Appalachia is just a 30-minute drive from the Kentucky state line. It was one of many settlements that sprang up around mines. Those clusters became known as “coal camps,” where housing and services were all operated by the coal companies in the arrangement made famous in Tennessee Ernie Ford’s classic 1955 hit.

Coal towns that flourished became full-fledged municipalities, like Appalachia, which was founded in 1898. As mining became safer and wages rose, Appalachia and surrounding towns became symbols of success of small town America, a rural answer to Detroit. Hospitals, schools, restaurants and shops sprang up, all fed by the trickle down from “King Coal.”

There is no end in sight for the current decline, according to a report by Downstream Strategies titled, "The Decline of Central Appalachian Coal and the Need for Economic Diversification."

“Coal production in Central Appalachia is on the decline, and this decline will likely continue in the coming decades,” states the 2010 report, which predicts production, which peaked at 290 million tons in 1997, will amount to less than 100 tons in 2035.

Many have moved away from Appalachia in search of work in recent years. Other breadwinners, reluctant to shatter the family bonds built over decades, spend their weekdays in far-off locations, sending money home and visiting on weekends or whenever they can. In Appalachia, they call it the “Suitcase Brotherhood.”

[image]

James Hibbitts was an upper middle-class banker in Appalachia back when there were loans to be made. Now, he works throughout the week for a natural gas company in Pennsylvania, some 375 miles away, returning for a few days when he can in order to be with his family.

“I am torn between the place I call home and the travel I am having to do to provide for my family, he said.

Environmental and liberal groups say there is no “war on coal,” only policies aimed at reducing pollution. They say many factors have contributed to the downturn in places like Appalachia, and the key to their turnaround is adaptation.

"The Appalachian coal market is confronting a perfect storm of mature coal resources, abundant and low-cost natural gas, deflated global coal prices, an influx of coal from Colombia and other countries, and competition with coal from other parts of the United States," said Alison Cassady, director of domestic energy policy for the Center for American Progress. "It does not help to blame the EPA and ignore the more fundamental market forces at work."

Rick Mullins, a local business owner in Appalachia and former state Senate candidate, agrees to some extent. He said the area has many attributes that could aid in a turnaround, but says federal aid is needed.

“What we are going to have to look to in the future is diversification,” Mullins said. “Owing to the unique history and natural beauty of the region, other avenues of employment could involve promotion of tourism in the region.

“If we could attain some kind of federal assistance in order to level the playing field, it would help greatly,” Mullins added.

Whited is not sure the Appalachia he grew up in will ever come back.

“I've got some good memories when things were better,” he said. “A lot of people had money and times were much more prosperous than they are now. Now there's really none of that, and it's empty for the most part.

“It's sad."