Community in Conflict: Hasidic Jews & Education

Part 1: Some Americans may not realize that Hasidic Jews shun many common secular practices widely accepted across cultural and national borders, including the basics of education. For example, there are several yeshivas, or Hasidic Jewish schools, in the New York area that only teach subjects in Yiddish. Previous yeshiva students share the impact of these practices in their lives.

This is the first of a three-part series on insular enclaves of ultra-Orthodox Jews, the struggles they face and the controversies that follow them.

It is, by choice, an intensely isolated and insular group, in which a Hasidic family with 10 children doesn’t raise an eyebrow.

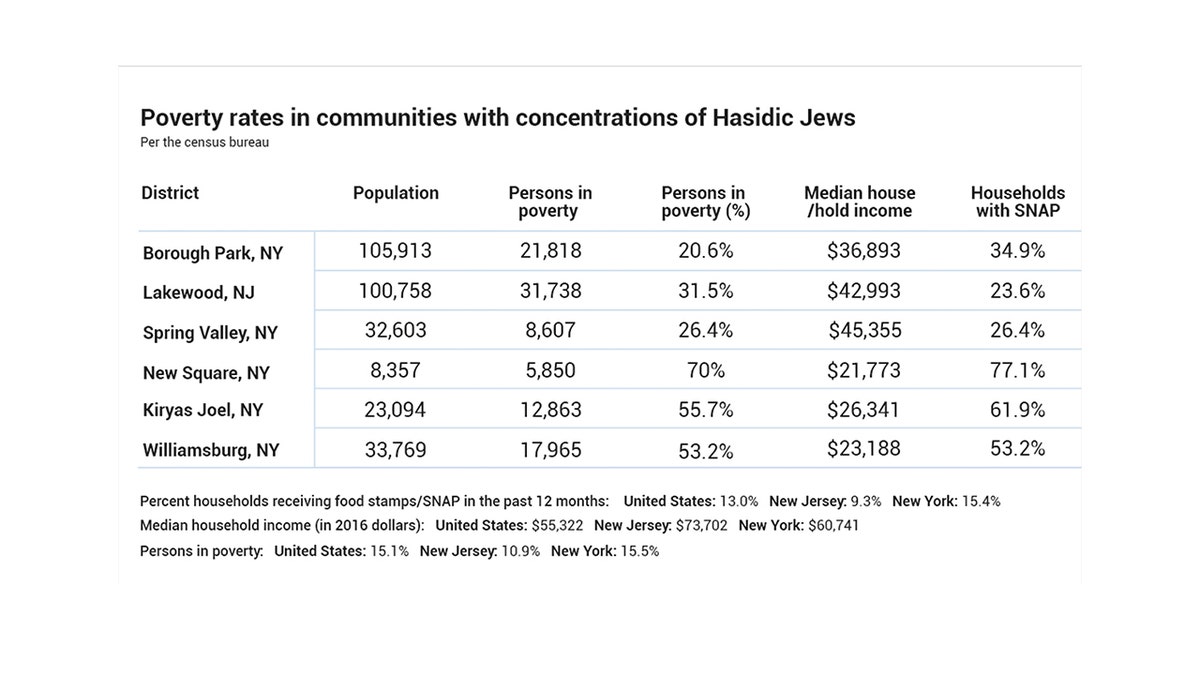

The big family units help explain why some communities they inhabit become among the poorest in the country, according to federal statistics on rates of welfare assistance, subsidized housing, food stamps and Medicaid.

Indeed, the U.S. town with the highest rate of people on food stamps is the all-Hasidic New York village of New Square, north of New York City, where 77 percent of residents rely on the program to eat, according to a new report.

Yet for all that need, the group is alternately courted, feared and vilified by politicians and businesses for its power to deliver huge, uncontested blocs of election-altering votes, donate hundreds of thousands of dollars to causes of its choosing, spark seismic shifts in real estate markets, public school budgets and city planning, and even hold hostage the country’s second-largest state budget.

This particularly strict group of Orthodox Jews, entrenched and concentrated primarily in a few communities in New York and New Jersey, has generated more indifference than curiosity -- until now.

That is because Hasidic communities have been outgrowing their enclaves and pushing to establish outposts in new towns, leading to pitched battles all over the New York region.

Hasidic residents and leaders say that bigotry is at the root of the battles -- many of which have ended up in court, which often have ruled in the religious community's favor. Their critics deny bigotry, and say it's a matter of sudden changes to towns that end up adversely affecting the quality of life.

A familiar pattern

"[Our critics] are insane. ... Our education system doesn't have a metal detector you have to go through, we have zero tolerance on drugs."

Critics of the Hasidic groups say development in many towns has followed a familiar pattern: The group moves into a community, then begins to overwhelm local government and social services with explosive population growth. That’s accompanied by rapid construction of low-cost, densely packed housing units -- typically townhouses -- though even these, eventually, can’t contain the growth. Hasidic leaders or developers with ties to them then buy up nearby homes, gain control of the local school board, ultimately gut public school budgets and divert funds to private Jewish schools.

There have been echoes of this pattern in places including Bloomingburg, a once-rural upstate New York town, and Toms River, N.J., to name but a few examples.

All this, while Hasidic households with very modest incomes collect millions in federal benefits, often because of large family sizes.

“They know how to game the system,” said Samuel C. Heilman, a sociology professor at Queens College of the City University of New York. “They know the ins and outs, or they get professionals and find out how to apply for things like Section 8" housing subsidies. "Their leadership is intertwined with the political system in order to get favorable entry.”

"It's usually done legally," said Heilman, author of the book “Who Will Lead Us?: The Story of Five Hasidic Dynasties in America,” in reference to how Hasidic Jews so expertly navigate the system.

The depiction of their use of government programs as "gaming" the system exasperates many Hasidim.

Rabbi Avi Shafran, the director of public public affairs for Agudath Israel of America, an umbrella organization for Hasidic and other ultra-Orthodox groups, told Fox News that characterizations such as "gaming" are pejorative ways to describe a talent for perceiving opportunities that, for these communities, can yield government services.

"That’s not ‘gaming the system,’" Shafran said, "it’s utilizing the social services net as it is intended to be used.”

The residents of Monroe, N.Y., another town north of Manhattan where the suburbs meet rural upstate, refer to tensions between themselves and Hasidic residents by just an innocuous pair of initials: “K.J.”

That’s the acronym for Kiryas Joel, a village within Monroe that is home to one of the most concentrated communities of the Hasidic sect called Satmar. The nearly all-Hasidic village population grew so much over the last few years – by about 6 percent each year, with the community's average age at about 13 -- it sought to annex hundreds of acres outside its borders to build hundreds of new units to place its residents. A decades-long battle between Monroe and K.J. ended in a referendum vote in November allowing the Hasidic village to secede, with a settlement giving it more than 200 annexed acres.

“We moved here 19 years ago for more space, a perceived quality of life,” said John Allegro, a Monroe resident. "It became an untenable situation.“

Watch: Community in Conflict: Hasidic Jews and Backlash

As for the Hasidim, “they have a desire and need to stay together, the women traditionally don’t drive, the men have to pray together in groups of 10,” said Allegro, who was part of a group of residents who brokered an agreement with K.J. officials over annexed lands. “The fact is, this packet of high-density housing in the middle of a rural and suburban community, it doesn’t fit, it’s a different aspiration from the way that people outside their community want to live.”

Isaac Abraham, advocate for Hasidic communities (Benjamin Nazario)

Monroe residents saw bloc votes from Kiryas Joel and Hasidic Jews in annexed lands in town help deliver victories to candidates who represented the religious community’s interests, which were diametrically opposed to their own.

“They’ll do what rabbis tell them to do,” Heilman said. “They will because they’ll get assistance.”

At a hearing on secession last fall in a packed auditorium in Monroe, Orange County Executive Steven M. Neuhaus described the power struggle with Hasidic residents as “a political Chernobyl that’s spilling over into other towns.”

Recently, under pressure from his Hasidic constituents, a single state senator, Simcha Felder, held up passage of New York’s $168 billion budget until he was promised the state wouldn’t interfere with the educational approach of yeshivas -- despite laws requiring all students to receive an education equivalent to that of public schools.

Naftuli Moster, who grew up in a Hasidic home and is one of 17 children, said that for the sake of votes, too many political leaders have turned a blind eye to the education standards at yeshivas.

"Some of the most knowledgeable and vocal opponents of the eruv are our [non-Hasidic] Jewish residents. ... No one feels they should be forced to live within the symbolic enclosure of another religious group, no matter what the religion."

Moster calls it a near-crime that breeds high poverty levels -- particularly when combined with the large families typical in the community and the lack of academic preparation to support them.

"I find it astonishing," said Moster, who founded a nonprofit, Young Advocates for Fair Education, to improve ultra-Orthodox schools. "One of the things we address is the impact on the taxpayer. A lot of people don't realize that non-public schools, even though they are called private and even if they are religious, get millions of dollars in government funding."

“The Orthodox leaders help them get as much as possible from government programs, but what they should be doing is helping them to become self-sufficient."

Shafran praised Felder.

“Simcha Felder, laudably, did what he felt he should for his constituents," the rabbi said. "That’s what representatives are supposed to do."

Claims of prejudice

Hasidic Jews and their supporters balk at any notions of a backlash, and accuse critics of anti-Semitic views.

"If these little towns want to putz around with racism, no problem. We have and we shall overcome them. ... They'll be running for cover, because the lawsuits will be coming."

“These are none other than racist low-life bastards,” is how Isaac Abraham, a leader in the Satmar sect in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, bluntly described the community’s critics. “I have no other words for them.”

Abraham argues that whatever the government allows in benefits, Hasidic families are “doing it legitimately.”

“There’s nothing wrong with that," said Abraham, a son of Holocaust survivors who was born in Austria and moved to Williamsburg when he was 2. "We [hear the] claim that illegal immigrants work and they pay taxes. But they’re still costing the government money and they’re illegal. Here we have [Hasidic Jews] who are legal, pay taxes, were born here, so what’s the problem? So you’re helping him live here so he can pay your taxes.”

Others say that Hasidic Jews are simply tapping into a system, flaws and all, that has been used to good effect by other special interests.

"Every group looks for political clout," Heilman said. "Lobbying is as American as apple pie. It's inherently corrupt, it's for special interest, not for the good of the larger society."

Shafran countered that it is right and noble to push forward in a community's best interests.

“Advocating for the needs of one’s community is not corruption," the rabbi said. "It is precisely what ethnic, religious and neighborhood groups are expected and encouraged to do in a democratic system.”

Many Hasidim say they would like to have more secular subjects, and note that girls in the community have more hours of non-religious English-language instruction and get a more well-rounded education.

But many other Hasidim take offense at portrayals of their schooling as deficient.

Some members of the East Ramapo Central School District Board of Education (AP)

"New York State law says that private schools must provide a substantially equivalent education to public schools," said Rabbi Joseph Kolakowski, whose children attend Hasidic yeshivas in Kiryas Joel and Bloomingburg, N.Y. "My argument is that the study of Jewish religious texts are not only equivalent, but superior."

"The Talmud contains high-level aspects of history, science, culture, language arts, mathematics, etc.," Kolakowski said, "as well as ethics, morals and critical thinking skills that are too often ignored in public schools. It isn't just sitting around all day singing hymns."

To Kolakowski and many other Hasidim, the community is singled out unfairly.

"The Hasidic community is the canary in the coal mine of [the issue of] religious freedom in America," he said. "There've been a lot of attacks on religious freedom against Orthodox Jews, Christians and Muslims. America was built on religious freedom."

The larger picture

Critics say it’s a matter of looking at the bigger picture – that the efforts by Hasidic leaders on behalf of their communities too often come at the expense of other residents who live in the same area.

Brooklyn Legal Services has complained that in this borough, Hasidic residents inundate government agencies with applications for such things as Section 8 housing the minute they become available, preventing other needy families from having access to such subsidized rentals, critics say.

“They’re masters of the application process,” said Martin S. Needelman, the executive director of Brooklyn Legal Services. “The part that is amazing is the amount of preparation [that goes into] applications. They clear people’s credit” and make sure to address anything that could raise a red flag.

Critics also accuse Hasidim of masking their income. Needelman said that much of the community operates in a cash economy, enabling some people to claim that their income is much less than it actually is. At the same time, he notes that a staggering number live at the poverty level, despite public assistance benefits, because of their large households.

“Your salary might be $40,000 or $45,000 a year, but if you have 12 children, that makes them very poor,” Needelman said.

Last year alone, clashes erupted in New York towns such as Monroe, East Ramapo and Bloomingburg, and in New Jersey towns including Mahwah, Jackson, Upper Saddle River and Montvale. Reasons for the friction vary: There is, for instance, the growing political power that Hasidim have gained at what others say is at the expense of the larger community.

There’s also the appearance of eruvs – a religious boundary sometimes fashioned out of wire affixed to utility poles -- Hasidim set up so that they where activities -- such as pushing a baby stroller or carrying canes and walkers -- may be carried out on the Sabbath, when they are not allowed to drive.

“An eruv was erected on our utility poles clandestinely in the middle of the night and without the towns’ permission in order to extend the size of their existing religious enclosure,” said Erik Friis, a businessman who lives in Upper Saddle River, N.J., where council members recently settled with an Orthodox group that filed suit when the town demanded the removal of the religious perimeter. (Under the settlement, reports said, the group can expand its eruv through town, but it was to be rerouted as close to the New York State line as possible, and use less-obtrusive black piping, not white.)

The Bergen Rockland Eruv Association argued in court documents that it secured permission from utility companies and that assertions that it acted covertly are inaccurate.

“We have nobody in our three towns who wants or requires an eruv,” Friis said. “When somebody comes from another state and starts installing things that have a certain religious significance around hundreds of telephone poles without the borough’s approval, and some of it was done at night, people get extremely upset. We have no forewarning of this, nor the ability to weigh in.”

Friis and other town opponents of the eruv argued that officials of the town, which has no Hasidic community, had capitulated to the eruv group, which asserted in a lawsuit that Upper Saddle River sought to undermine its religious freedom.

“Some of the most knowledgeable and vocal opponents of the eruv are our Jewish residents” who aren't Hasidic, said Friis, who founded the group Citizens for a Better Upper Saddle River. “A common complaint is that no one feels they should be forced to live within the symbolic enclosure of another religious group, no matter what the religion.”

Yehudah L. Buchweitz, who served as pro bono counsel to the Bergen Rockland Eruv Association, told Fox News the law was on the side of the Hasidic community.

“The recent lawsuits in New Jersey ... ensure that families are able to enjoy the same religious freedom as so many others throughout Bergen and Rockland counties and beyond," Buchweitz said. "The ... settlements preserve and protect the people’s right to an eruv, which has been repeatedly endorsed by state and federal courts in every case to have considered the issue."

"There is an eruv in 23 of the largest 25 cities in the United States," he asserted. "In almost every instance, the eruv is constructed without controversy and is viewed positively by the community as a symbol of diversity.”

Beware 'the next East Ramapo'

Residents of many towns where Hasidic Jews have moved in say the group tends to take control of local politics and undermine the quality of life for those outside its religious enclave.

The New York Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit in November against the East Ramapo, N.Y., school district and the State Department of Education alleging that the election system – controlled by Hasidic Jews – denies “minority citizens an equal opportunity to have a voice in the future of their community’s public schools.”

The district, once a high-performing one, has suffered, many residents say, since Hasidic Jews became a majority of the nine-member school board in 2005, cutting funds for public schools and diverting them to their private schools. The district cut 445 positions and reduced full-day kindergarten as well as sports and arts programs. The cuts, the NYCLU asserts, have resulted in four out of five public school children in grades three through eight lacking proficiency in math and English.

The late Rabbi Mordechai Hager, who was leader of one of the largest Hasidic sects in the United States, was said to have been unhappy about Orthodox Jews who did not use public schools dominating the East Ramapo school board.

The New York Times said the rabbi, whose Hasidic village, Kaser, is part of the East Ramapo school district, "viewed the situation as unnecessarily provocative."

“He did not believe in public confrontation with the secular world," Yosef Rapaport, a media consultant for Agudath Israel of America, told The Times.

East Ramapo school officials didn't return calls and emails from Fox News.

In towns that have fought Hasidic Jewish political power, the saying that they don’t want to be “the next East Ramapo” has become a familiar mantra.

Some East Ramapo families, saying they're exasperated and feel powerless, have moved or plan to do so.

Yolanda Maya reluctantly moved to Suffern from Spring Valley two years ago after what she said was a dip in educational quality at East Ramapo schools, particularly for special-needs students.

“I was there since my daughter was born,” Maya said. “My daughter had only one good year; that was kindergarten. They cut programs she needed, like the integrated classes – they have special-needs children with other children in the same class. And kids with special needs really benefit from art and music programs, and they cut them.”

Maya said her daughter, who has learning disabilities, is gradually improving because of the resources in her new district, but that she remains scarred by the deficient education and support in East Ramapo.

“My daughter used to have a healthy self-esteem,” she said, “but the school system made her feel not smart, worthless.”

Steven White, who was educated in the district and sent his two sons there, recalls when the schools were among the best in the state. The district, he recalled, had cutting-edge programs and groomed students to qualify for the nation’s best colleges. His youngest son graduated in 2012, right when the district was hit hard by deep cuts in staffing and programs.

“We had a school board that was under the control of people who didn’t use public schools for their own children, and who themselves had not gone to public schools,” White said.

Though his kids are out of the school system, White has become involved in campaigns to put people who want to strengthen public education on the school board, and he frequently went to Board of Education public meetings to voice concerns. Other former East Ramapo students, now adults, formed a group to try to bring back quality education.

White said he often encountered indifference and silence when he asked questions or raised a concern.

“We were treated with derision by the school board,” White said. “The school budgets were always voted down; they vote in blocs. You can boil it down to the fact that they don’t value public education."

“The idea of public education is to make sure that all children are prepared for tomorrow, and we all benefit from that. The kid you educate might be the doctor that saves your life one day, or the one who creates the next great app.”

Isaac Abraham, an advocate for the Hasidic community, said that others should accept that the group is growing and will look out for its own best interests.

He also takes exception to the idea that Hasids must explain why they live as they do.

“They’re not seeing what we’re seeing,” Abraham said. “If we got to their schools, from town to town, I’ll give you a low number, 10 percent are on drugs, 5 percent are in the system, already as criminals. Our education system doesn’t have a metal detector you have to go through, we have zero tolerance on drugs."

With this in mind, he said, the less Hasidic kids know about the outside world, the better.

"If these little towns want to putz around with racism, no problem," Abraham said. "We have and we shall overcome them. ... They'll be running for cover, because the lawsuits will be coming."

This article has been edited since its publication earlier this week to incorporate new information and quotations.