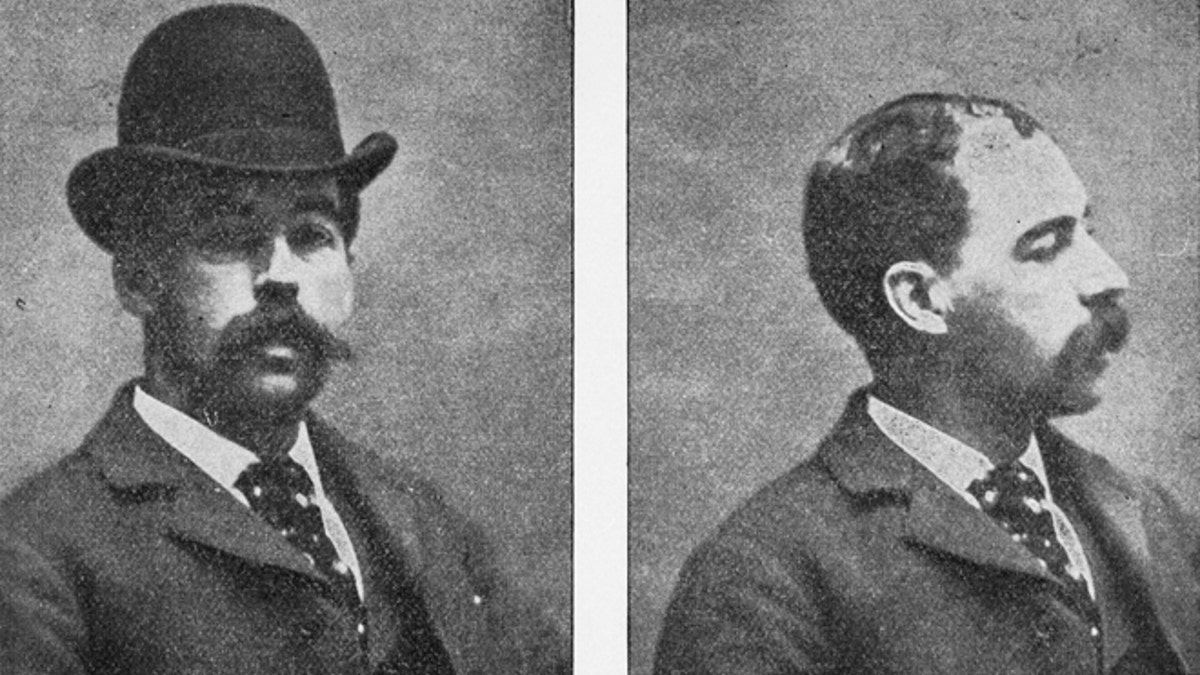

Front and profile portraits of Herman Webster Mudgett, alias H.H. Holmes, from book, titled The Holmes-Pitezel Case, a History of the Greatest Crime of the Century. (Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum)

On the morning of May 7, 1896, thousands of people gathered outside the high stone walls of the old Moyamensing Prison in South Philadelphia to await the hanging.

Herman Webster Mudgett, better known to the world as H.H. Holmes or “America’s first serial killer,” was set to hang for the horrific murder of his late business partner, Benjamin Pitezel. While Holmes confessed to killing 27 people and is rumored to have done in more than 200 in his Chicago home, dubbed the “Murder Castle,” it was the death of Pitezel – whom he burned alive to collect $10,000 in insurance money – that sent him to the gallows.

At around 10:15 in the morning, the prison’s superintendent fitted the noose around Holmes’ neck and the trap was sprung. After the drop, Holmes twitched uncontrollably for 15 minutes as he slowly strangled to death, but after 20 minutes on the rope prison officials officially declared him dead.

But was he really dead?

Following the hanging, rumors spread far and wide that Holmes – a master con man and manipulator – had paid off prison guards to hang a cadaver or some unsuspecting fellow inmate in his place and let him slip off into hiding in South America. Now, almost 121 years later and following a request from a descendent of Holmes, a Pennsylvania court has issued an order to have the alleged remains of the murderer dug up from his unmarked grave in Holy Cross Cemetery outside of Philadelphia.

“Why are we still fascinated by him?” John Russick, vice president for interpretation and education at the Chicago History Museum, told Fox News. “Part of it is the morbid curiosity in his crimes, but part of it is the effort to confirm that he is dead and was not actually able to outwit the law. There is the desire to confirm that legend is not true.”

While the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Anthropology will conduct forensic testing on the remains, the team digging up Holmes’ coffin won’t have an easy time. The Chicago Tribune reported around the time of his death that Holmes requested to have his body encased in several barrels of cement, weighing around 3,000 pounds, in an effort to “ensure his body against the vandalism or scientific curiosity of ghouls.”

That's slightly ironic for a guy believed to have dismembered and skinned the bodies of his victims before tossing what was left down a greased chute that led down to a lime pit and selling the remaining bones.

Holmes, a pharmacist by training who studied at the University of Michigan, started his criminal career by pawning off water as patent medicines, but was early on suspected of killing several people to either collect their life insurance or just to cover his tracks.

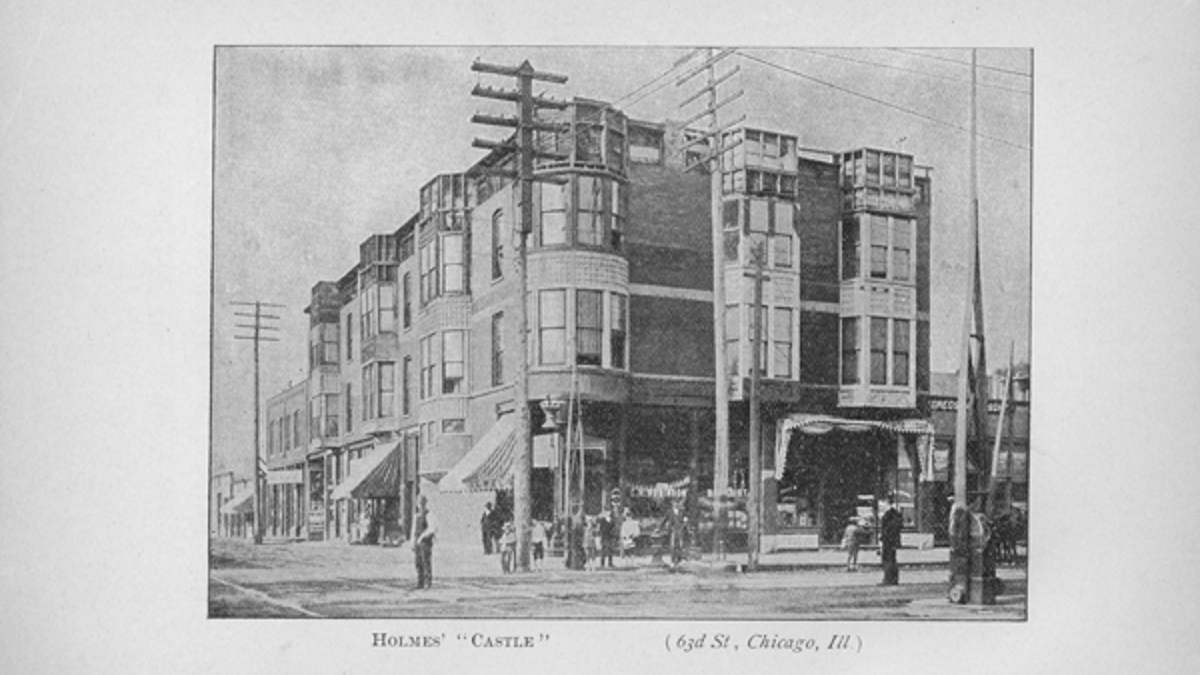

Exterior view of residence of Herman Webster Mudgett, a.k.a. H.H. Holmes, on 63rd Street. Mudgett's home was named the Murder Castle. Published in a book titled The Holmes-Pitezel Case: A History of the Greatest Crime of the Century. (Exterior view of residence of Herman Webster Mudgett, a.k.a. H.H. Holmes, on 63rd Street. Mudgett's home was named the Murder Castle. Published in a book titled The Holmes-Pitezel Case: A History of the Greatest Crime of the Century.)

But Holmes’ licentious legend doesn’t truly begin until the construction of his “Murder Castle” in 1887 – a sprawling, three-story mixed use building with his pharmacy on the ground floor and a maze-like array of rooms above that featuring trap doors, sliding walls, airless vaults and dissecting tables. There was also a crematorium, a lynching parlor, stretching racks and the aforementioned greased slide.

Holmes main targets were believed to be young women whom he lured in with the promise of room and board or with jobs in his pharmacy. His murderous exploits during the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition were detailed in Erik Larson’s 2003 best-selling, non-fiction “The Devil in the White City.”

"The atrocities of which he was convicted are almost unparalleled in the history of crime — shocking alike for their enormity and the cold-blooded, deliberate way in which they were committed," the Chicago Tribune reported in 1896. "He attributed his natural relish for crime to the fact, as he put it, 'he was born with the devil in him.'"

After the third floor of the castle caught fire in 1893, Holmes fled town amid accusations of arson. With insurance companies chasing him down, he went to Texas and Missouri before ending up in Philadelphia, where he set up a phony patent office with Pitezel.

Following the killing of his business partner, Holmes took off with three of Pitezel’s five children on a road trip around the Northeast and Canada. He was eventually caught in Boston by agents working for an insurance agency in late 1894 and sent back to Philadelphia.

The atrocities of which he was convicted are almost unparalleled in the history of crime — shocking alike for their enormity and the cold-blooded, deliberate way in which they were committed.

The decomposed bodies of Pitezel's daughters, 15 and 11, were later discovered buried in the cellar of a home Holmes’ rented in Toronto and investigators found the charred remains of Pitezel’s son stuffed in a chimney in an Indiana rental home.

Holmes was found guilty of killing Pitezel in the fall of 1895 and sentenced to hanging.

"I have every attribute of a degenerate – a moral idiot," Holmes wrote in a confession printed in the Philadelphia Inquirer. He added that he was physiologically morphing into a monster, with one side of his face “marked by a deep line of crime and being that of a devil.”

Most believe that the story of Holmes’ faking his own death is just a conspiracy theory as around 70 people -- some who knew him personally – witnessed the hanging and Holmes, who the New York Times said remained “cool to the end,” made a last-minute denial of killing Pitezel.

Mudgett family lore, however, states that the killer “…managed to escape through some subterfuge and that someone else was hanged and buried at the grave site...”

Forensic experts say that as long as the remains have been protected over the years – and what good is encasing a body in 3,000 pounds of concrete if not to protect it? – the anthropologists at Penn should be able to find a usable sample of DNA that could finally put to rest the question of whether or not “America’s first serial killer” actually died inside those prison walls.

“It’s highly unlikely [Homes escaped execution]… this seems like a pretty cut and dry case,” Russick said. “But crazier things have happened before. So, who knows?”