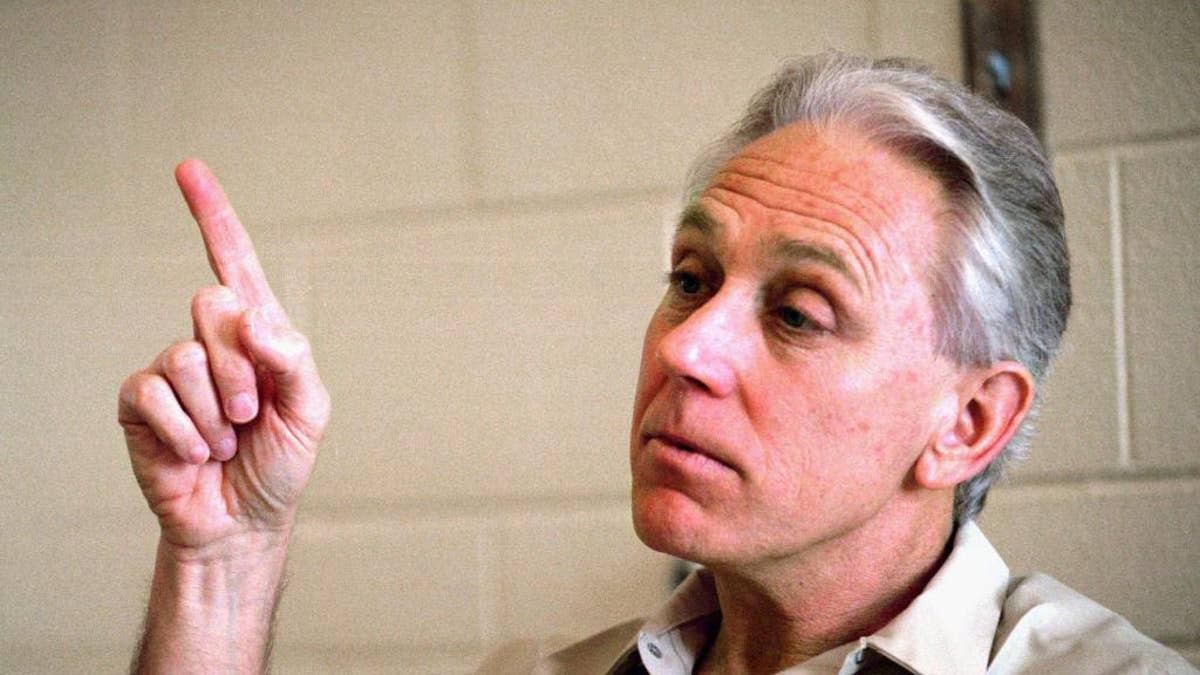

Convicted killer and former Army doctor Jeffrey MacDonald behind bars in 1995. (AP Photo/Shane Young)

RICHMOND, Va. – A former Army surgeon who has always insisted he was wrongly convicted of slaughtering his pregnant wife and their two young daughters nearly 50 years ago won't give up, even if his latest appeal fails to clear his name, his lawyer says.

Jeffrey MacDonald is "going to keep fighting and will continue to maintain his innocence until the end of his days," Attorney Hart Miles said after a hearing at the 4th U.S. District Court of Appeals on Thursday.

After decades of failed appeals, MacDonald now hopes the same court that briefly reversed his convictions in 1980 will side with him again. His attorneys say evidence uncovered since then proves he wasn't the killer.

The 73-year-old has maintained that a group of drug-fueled hippies slaughtered 26-year-old Colette McDonald and their daughters Kimberley, 5, and Kristen, 2, on Feb. 17, 1970, and that his own wounds resulted from his failed attempt to protect his family.

MacDonald told the police he called to their home inside Fort Bragg in North Carolina that he was awakened by the screams of his wife and daughters, then was attacked by three men and a woman with long blond hair and a floppy hat who carried a lighted candle and chanted "acid is groovy; kill the pigs."

Prosecutors still contend that the evidence shows MacDonald used a knife and an ice pick to kill them before stabbing himself with a scalpel. They say he donned surgical gloves and used his wife's blood to write the word "PIG" over their bed to imitate that year's Charles Manson murders.

It became known as the "Fatal Vision" case, the title of a true-crime book MacDonald had invited author Joe McGinniss to write to demonstrate his innocence. Instead, McGinniss became convinced of his guilt. McGinniss eventually agreed to pay MacDonald $325,000 to settle breach of trust claims.

MacDonald is now challenging a judge's refusal in 2014 to grant him a new trial based on new evidence, including three hairs found at the scene that don't match the family's DNA, and a statement from Jimmy Britt, a deputy U.S. marshal who accused the prosecution of intimidating a key witness.

Britt told defense attorneys in 2005 that Helena Stoeckley, a troubled local woman MacDonald had identified as one of the attackers, told prosecutor Jim Blackburn that she was at the scene of the killings. Britt said Blackburn threatened to indict her with murder if she said so in court. When Stoeckley got on the stand, she said she couldn't remember where she was that night.

Stoeckley also told several others that she was present for the murders, but the district court said her heavy drug use makes her alleged confessions unreliable. Britt and Stoeckley have both since died.

U.S. Attorney John Bruce described the defense evidence as insignificant and told the judges Thursday that the case against MacDonald remains strong.

Significant pieces of Britt's story were proven wrong, making him an unreliable witness, Bruce told the judges. The hair — which MacDonnell's attorneys say must have come from the intruders — could have been anyone's, Bruce said.

"This was a busy apartment with a young family with scores of people around them," Bruce said. "There was dog hair on the bed. Was that evidence of intruders? The MacDonalds didn't own a dog."

Appellate Judge Diana Gribbon Motz also questioned how the hair evidence helps MacDonald's case, noting that it did not match Stoeckley's DNA either.

"It's not as though you have this hair tied to another person of interest," Motz told MacDonald attorney Joseph Zeszotarksi Jr.

A ruling from the 4th Circuit could take months or more.

MacDonald, who is serving three consecutive life terms in Cumberland, Maryland, refused to apply for parole for years after becoming eligible in 1991, arguing that doing so would essentially amount to admitting guilt. He finally applied in 2005 — in part out of a desire to live with the woman he married in 2002 — but was denied early release. He is not eligible for parole again until 2020.

"It would be a dishonor to their memory to compromise the truth and 'admit' to something I didn't do — no matter how long it takes," MacDonald said in a 2000 letter to his now-wife, Kathryn MacDonald, which she provided to The Associated Press.