DALLAS – After her oldest daughter was killed in May 2016, Michelle McDaniel and the rest of her family isolated themselves in their small Texas town out of fear that the unknown killer could be standing in line with them at the grocery store or passing them on the street.

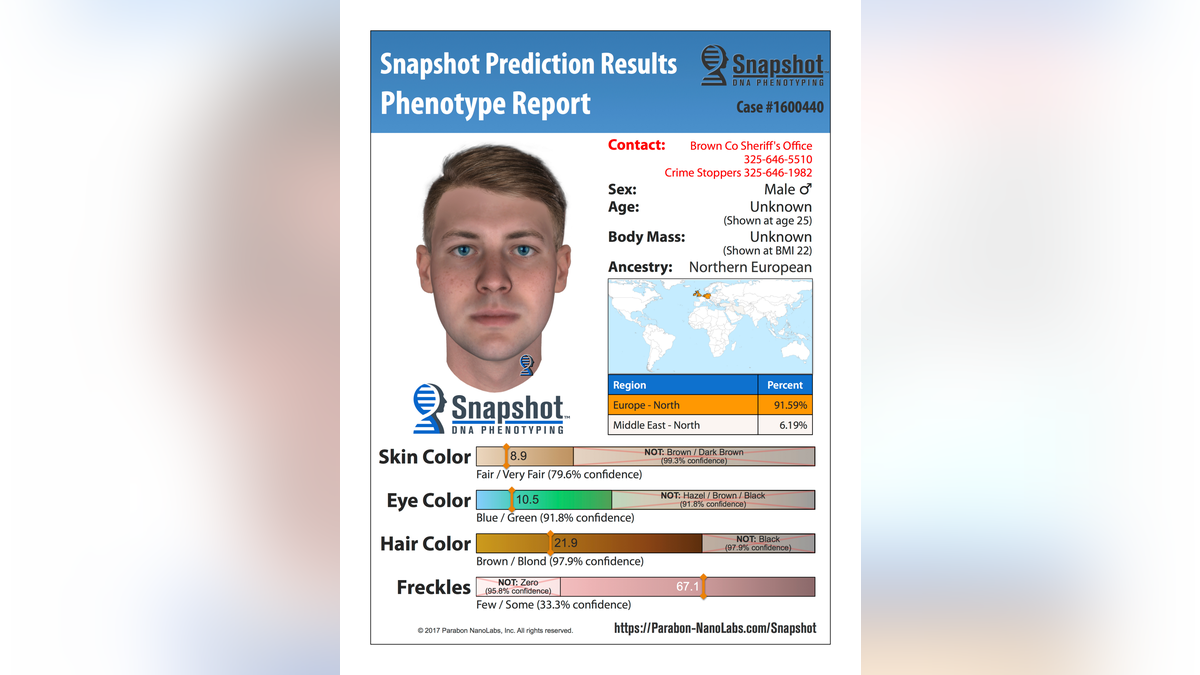

Then early last month, Brown County sheriff's investigators sent McDaniel a sketch of the man they suspected in her daughter's death, despite having no witnesses. The sketch was created using DNA found at the crime scene; a private lab used the sample to predict the shape of the killer's face, his skin tone, eye color and hair color.

Within a week, the sheriff's office had a suspect in custody.

For McDaniel, the DNA sketch technology known as phenotyping was an answered prayer. For law enforcement officers, it's a relatively new tool that can generate leads in cold cases or narrow a suspect pool. But for some ethicists and lawyers, it's an untested advancement that if used incorrectly could lead to racial profiling or ensnaring innocent people as suspects.

At a news conference a week after the sketch was released, Brown County Sheriff Vance Hill announced that 21-year-old Ryan Riggs had confessed to the beating death of 25-year-old Chantay Blankinship. Authorities have said they believe the killing was premeditated but have not released a motive. Riggs is being held without bond on a capital murder charge in the Brown County Jail about 170 miles (275 kilometers) southwest of Dallas.

"My son called me after seeing the sketch and said, 'Mom, I think I know this kid. He used to bully me in school.' He sat behind her in church. His mom picked her up every week and took her to church. ... He was best friends with my niece and her friends. And we wouldn't have known," McDaniel said.

Several private companies offer phenotyping services to law enforcement to create sketches of suspects or victims when decomposed remains are found. The process looks for markers inside of a DNA sample known to be linked to certain traits. Police in at least 22 states have released suspect sketches generated through phenotyping.

It works like this: Companies have created a predictive formula using the DNA of volunteers who also took a physical traits survey or had their face scanned by recognition software. That predictive model is used to search the DNA samples for specific markers and rate the likelihood that certain characteristics exist.

For some ethicists and lawyers, however, releasing a sketch of a suspect without any witnesses seems like a dangerous proposition. Jay Stanley, a senior policy analyst at the American Civil Liberties Union, said that from what scientists have said and written, not enough is known about the link between genes and facial features to rely on the technology to produce a suspect.

"You can lose weight, gain weight, change gender, grow a beard, have plastic surgery," Stanley said. "It risks ensnaring innocent people in webs of suspicious investigations. It risks playing on existing societal racial prejudices. It risks diverting investigations down wild goose chases. If this technology were used to set up dragnets say to bring in every albino person in an area as a suspect because the DNA seemed to show someone had that trait, that's where we would object."

Stanley also noted previous issues with forensic science advancement in the past, including bad practices in DNA testing from hair samples a few years ago.

Steve Armentrout, the CEO of Parabon NanoLabs, which created the Brown County sketch, said phenotyping isn't meant to replace court-tested methods of identifying suspects. He said it's an investigative tool.

"In every case we are involved in there is DNA. This isn't meant to provide a positive identification. It's meant to jog someone's memory," he said. "The greatest value of the tool from an investigative perspective is efficiency, the ability to exclude portions of the suspect pool."

In the Brown County case, Hill said Riggs saw the sketch, went on the run for a few days and then confessed to the killing in front of the congregation at the church where he and Chantay both attended services. Hill had not said whether DNA tests were run yet to see if Riggs' DNA matches that found at the scene.

No attorney information was listed for Riggs, and his parents didn't return calls seeking comment on the case.

In Central Texas, Brazos County Sheriff Chris Kirk likened the skepticism about the technology to officers saying digital cameras wouldn't hold up in court when they were introduced because the photos could be manipulated.

"Now every department in every state uses them," he said.

National Geographic paired with Kirk's department earlier this year and paid the $3,600 to submit suspect DNA from the 1981 slaying of Virginia Freeman for a sketch in exchange for being able to film the search process. The department released a sketch of the potential killer when he was in his 20s and another age progressed to about 70.

"It has definitely renewed the interest of the public in the case. We've gotten a number of tips and phone calls," said Kirk, who is the only remaining officer in his department who was around when Freeman was found bludgeoned, strangled and stabbed to death. "That was a really traumatic crime for that family, for the department and for the whole community."

As of this week, no arrests had been made.

___

Follow Claudia Lauer on Twitter at http://twitter.com/ClaudiaLauer. Sign up for the AP's weekly newsletter showcasing our best reporting from the Midwest and Texas: http://apne.ws/2u1RMfv