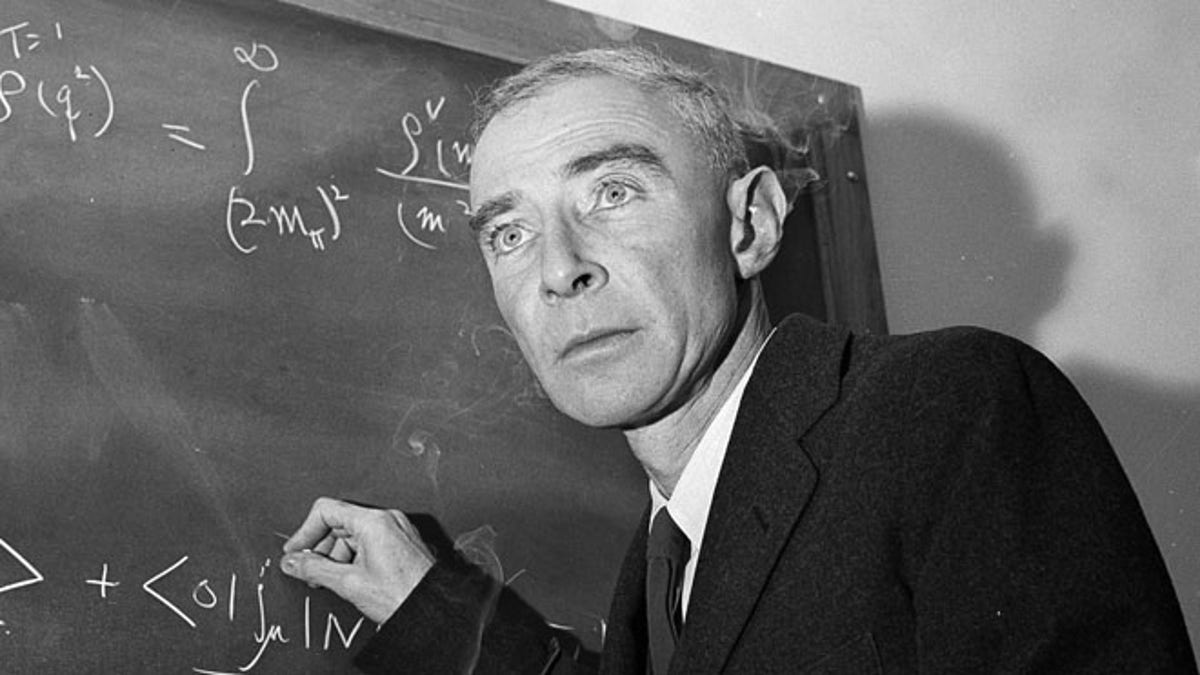

Dec. 15, 1957: Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, creator of the atom bomb, is shown at his study in Princeton University's Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, N.J. (AP Photo/John Rooney, File)

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. – After more than half a century of intrigue and mystery, the U.S. Department of Energy has declassified documents related to a Cold War hearing for the man who directed the Manhattan Project and was later accused of having communist sympathies.

The department last week released transcripts of the 1950s hearings on the security clearance of J. Robert Oppenheimer, providing more insight into the previously secret world that surrounded development of the atomic bomb and the anti-communist hysteria that gripped the nation amid the growing power of the Soviet Union.

Oppenheimer led the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos National Laboratory, which developed the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II. The secretive projects involved three research and production facilities at Los Alamos, New Mexico, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Hanford, Washington.

The once-celebrated physicist lost his security clearance following the four-week, closed-door hearing. Officials also alleged that Oppenheimer's wife and brother had both been communists and he had contributed to communist front-organizations.

Steven Aftergood, director of the Project on Government Secrecy for the Federation of American Scientists, said the release of the documents finally lifts the cloud of secrecy on the Oppenheimer case that has fascinated historians and scholars for decades.

"This was a landmark case in U.S. history and Cold War history," Aftergood said. "It represents a high point during anti-communist anxiety and tarnished the reputation of America's leading scientist."

The Energy Department had previously declassified portions of the transcripts but with redacted information.

Aftergood, who had only scanned the hundreds of pages of newly declassified material, said the documents provided more nuanced details about the development of the atomic bomb, debates over the hydrogen bomb and reflection on atomic espionage.

The documents also show how unfairly Oppenheimer was treated immediately following World War II, Aftergood said.

Most of the material would be of more interest to scholars because of the inside debates and discussions, Aftergood said.

After the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer served as director of Princeton's Institute for Advanced Study until he retired in 1966.

President Lyndon B. Johnson later tried to erase the embarrassment of Oppenheimer's treatment by honoring him with the Atomic Energy Commission's Enrico Fermi Award in 1963.

Oppenheimer died of throat cancer in 1967.