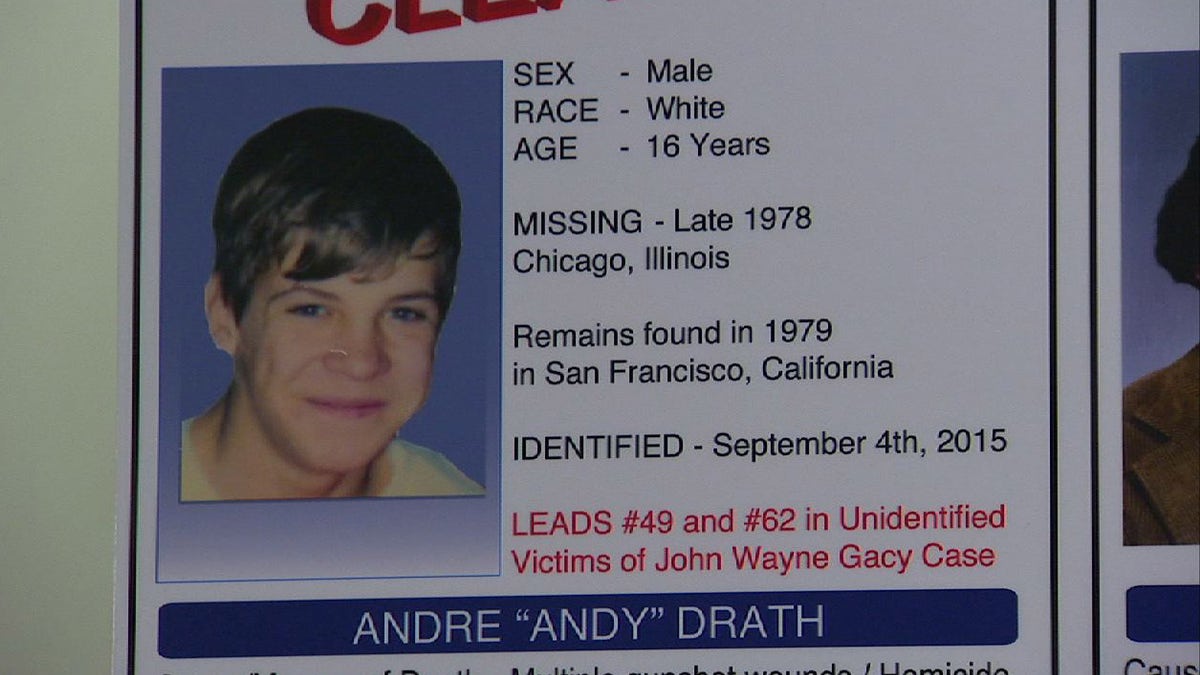

Andre Drath left home at 16 and died on the streets of San Francisco.

CHICAGO – It’s been 36 years since Willa Wertheimer last saw the brother she knew as Andy.

Andre Drath was just 16 when he left home in Chicago for San Francisco and was never heard from again, leaving his loved ones in uncertain despair over his fate. But the mystery of what became of her brother was finally solved as a byproduct of an investigation into one of the most infamous serial killers the nation has ever known, John Wayne Gacy.

Of the 33 males found buried in Gacy’s crawl space, eight were never identified. When Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart reopened the case in 2011 with the goal of learning their names, his office sought DNA samples of family members of Chicago-area boys who vanished in the late 1970s. Wertheimer sent hers, and while Andy was not one of the eight, her sample matched one in the federal database from a John Doe gunned down decades ago on the streets of San Francisco.

“Although I’m terribly sad, the knowing is so much better,” Wertheimer, who still lives in Chicago, told Fox News. “It seemed like a long shot for a kid living on the fringe, after 35 years.

“Although I’m terribly sad, the knowing is so much better.”

“Andy had become an invisible life, living on the streets,” she said.

While Wertheimer’s hunch that her brother had been a victim of Gacy, the monster who dressed as a clown to prey on young boys, proved incorrect, it did lead to closure. When police found Drath, DNA identification was unavailable but police had kept tissue samples in the hope of a future identification.

Some 12 other cold cases were similarly solved, thanks to the renewed focus on the unidentified Gacy victims. Dart’s nationwide call for DNA samples came after investigators determined Gacy had traveled far more than previously known, meaning his victims could have come from as far away as California or Canada.

Gacy, (l.), was a monster, but he was not involved in the death of Steven Soden, (r.).

“The very nature of this, it’s always going to be a bit of a long shot given the people that he targeted and the breadth of his killing,” Dart said. “When we began this endeavor we were hopeful but not naïve.”

The DNA samples from dozens of people with missing relatives also led to police to identify others in unsolved cases, including Daniel Noe, a Peoria, Ill., man who disappeared in 1978 when he was just 21. In 2012, a DNA sample from Noe’s relative was matched to one from a body found on Mount Olympus, near Salt Lake City. Foul play was not suspected in that case.

Ron Soden, now 75, of Washington state, had sent his sample to Dart’s office on the chance that his long lost kid brother had been a Gacy victim. It turned out that the death of Steven Soden, who was just 16 when he ran away from a New Jersey orphanage in 1972, was unrelated to Gacy. But the sample turned up a match to skeletal remains found in a New Jersey state park in 2000.

In three other cases, DNA samples collected as part of the Gacy probe led to living men, including one in Las Vegas, and another who had been living in Oregon with his spouse and children.

The effort has also led to the identity of one of the eight previously unknown victims buried at Gacy’s home – its original objective. In all, more than 50 people have so far submitted their DNA to the Cook County Sheriff’s Office to be tested against the DNA of the unidentified Gacy victims.

Wetheimer had a message for others with missing relatives.

“To those whose loved ones have gone missing even long ago, I stand here as a testament that you should never lose hope for closure that you’ve longed for,” she said.

Gacy was executed in 1994.