(The Associated Press)

For the last two years, Dallas’ Deputy Mayor ProTem Erik Wilson has tried in vain to convince a grocery store to set up shop in his district – an area of the Texas city that hasn’t had a supermarket since the 1980s.

After pleading with store owners to bring a full-size grocery store to what has been described as the “southern Dallas food desert,” Wilson and other city officials decided to sweeten the deal by promising $3 million to any store willing to sell healthy foods and fresh produce in the district.

But even with cash on the table, there were no takers.

“We could not get anyone to take advantage of it,” Wilson told FoxNews.com. “Hopefully one day we’ll find that elusive unicorn.”

H-E-B, the San Antonio-based company that recently announced it will open two Central Market stores in the northern part of Dallas, declined FoxNews.com’s request for comment.

Wilson’s district, however, is not alone in lacking access to a proper grocery store.

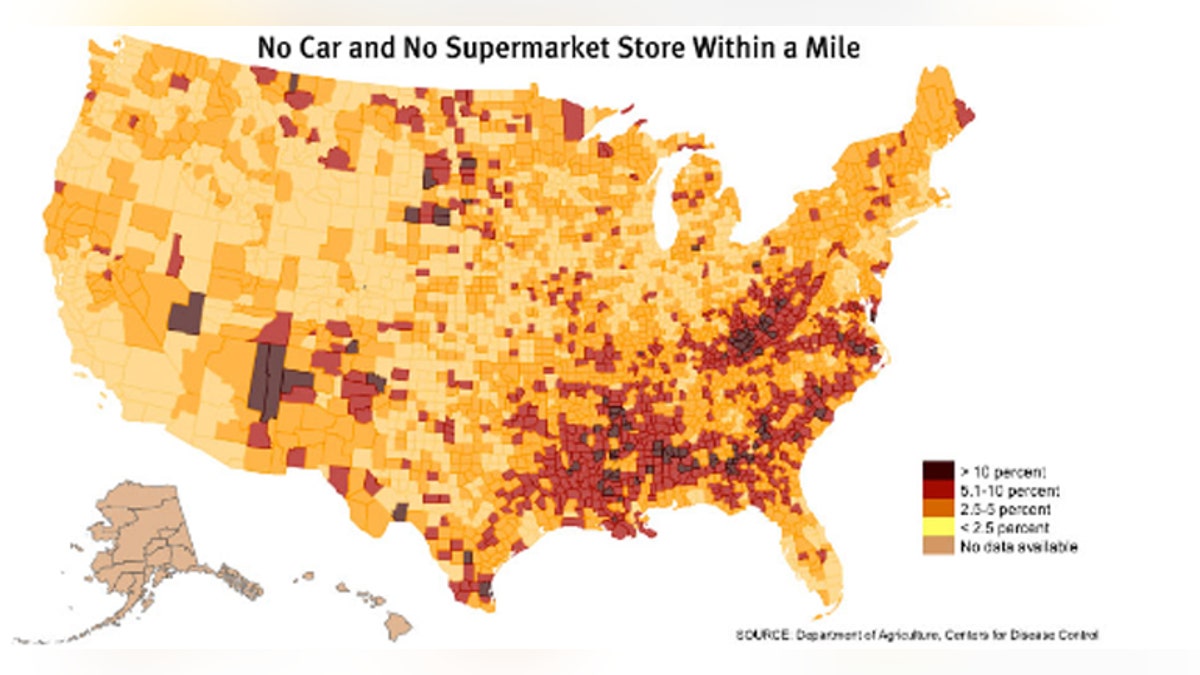

According to U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) statistics, around 23.5 million people across the country live in food deserts – described by the USDA as “parts of the country vapid of fresh fruit, vegetables, and other healthful whole foods” –and nearly half of those people live in low-income households.

(USDA)

“It’s quite tough to get grocery stores to move into these areas,” Jessie Handbury, an assistant professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, told FoxNews.com.

The grocery business is notorious for its low profit margins of only one to two percent, where produce that doesn’t sell literally rots on the shelf, and for the cutthroat competition from big box stores like Walmart and Target encroaching on the market that keep supermarkets from expanding to all but the safest locales.

Reticence from grocers, however, only explains part of the reason why food deserts exists. Experts say that both the cost of food and the shopping habits of customers in low-income areas make it economically unviable for stores stocking items like fresh produce and meats to open up shop.

A study published last year by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that only a tenth of the variation in food people bought could be explained by their proximity to a grocery store and instead people’s incomes, and even education levels, were better indicators.

“Low income families buy food with the idea that they want to keep their families from being hungry,” Anne Palmer, a food researcher at Johns Hopkins University’s Center for a Livable Future, told FoxNews.com.

Palmer added that people in neighborhoods without access to nearby grocery stores aren’t used to buying fresh produce and thus are unlikely to buy it if a supermarket opens up because it constitutes a risk. Food that your family doesn’t eat is wasted money, she added.

“If we want people to eat healthier, we need to subsidize healthy foods for low-income shoppers,” Palmer said.

One example of this tactic is in Chester, Pa., a city of around 34,000 people about 20 miles south of Philadelphia that until October 2013 had not had a grocery store for 12 years.

A little over three years ago, Philabundance – a local food bank – raised $7 million in startup funds and opened the non-profit grocery store Fare & Square in Chester.

Instead of immediately becoming a local favorite, however, the store's stock of fresh food wasn’t winning over customers accustomed to the processed food sold at nearby convenience stores and fast food restaurants.

“These eating habits were formed a longtime ago,” Handbury said. “If you grew up around someone who didn’t cook - or didn’t have the time, space or money to cook - than you would lack the taste for certain foods.”

The store quickly began to rejigger what it carried – adding Caribbean and Latin American foods that customers asked for – and stocking up on snacks and sodas as well as fruits and vegetables. More importantly, experts say, the store also began offering cashback incentives and lower prices on healthy and fresh foods.

(Fare & Square)

While the store is not yet operating in the black - it is still subsidized by Philabundance and as of this summer needs to take in 20 percent more to break even – the store’s creators say that once the balance of foods was figured out, sales began to grow.

“Once we’ve got that figured out, we’ve got to let more people know about the store,” Martin Meloche, a retired food marketing professor who developed Fare & Square’s business model, told Next City. “It’s doing well. We’d like to see it doing better.”

Fare & Share’s model may be promising, but with its profit losses it’s unlikely to be picked up as a platform for big chain grocers looking to move into the so-called food deserts and would need a friendly benefactor like Philabundance to keep it afloat.

“They need a sufficient demand to cover their operating costs,” Handbury said. “The inventory cost of keeping food on the shelves alone is very high.”

In southern Dallas – which includes Wilson’s 57-mile-long District 8 – there have been a handful of grocery stores that have opened in recent years, including some Walmarts, a few Aldis and El Ranchos and a Save-A-Lot that cost the city $2.8 million. But the area still remains vastly underserved, Wilson said, and it doesn’t appear like the area will see a new supermarket anytime soon.

So unless a nonprofit steps up to the plate in southern Dallas, Wilson and the city’s $3 million will have to wait for “that elusive unicorn.”

“The money’s still there if someone wants to help partner with us and help us end the food desert in southern Dallas” he said.