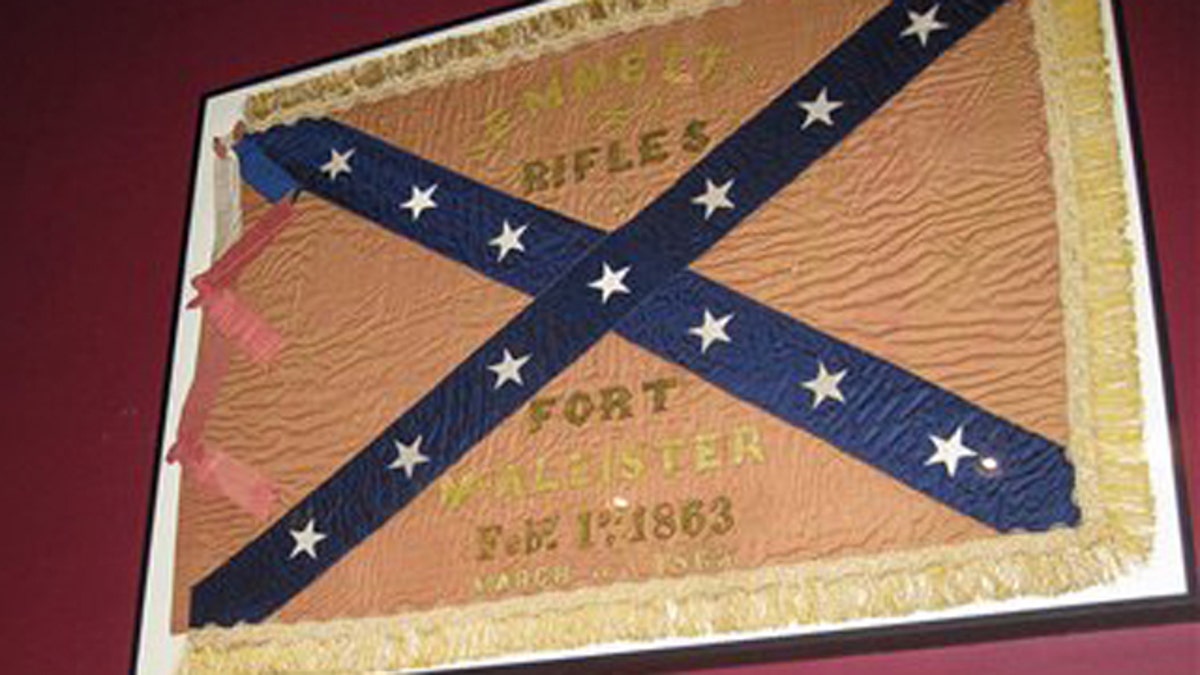

March 21, 2012: In this photo, a Confederate unit flag that belonged to the Emmett Rifles, a Georgia-based company during the Civil War, hangs at Fort McAllister state park in Richmond, Ga., 148 years after the fort fell to Gen. William T. Shermans army. (AP)

RICHMOND HILL, Ga. – As Fort McAllister fell to the Union Army of Gen. William T. Sherman days before Christmas in 1864, one of his artillery officers seized the Confederate flag of a vanquished company of Georgia riflemen.

The officer carried the silk banner home to Maine as a souvenir, and it stayed in his family for three generations in a box along with a handwritten note: "To be return to Savannah or Atlanta sometime."

Nobody knows for sure why the late Maj. William Zoron Clayton wanted his Civil War trophy flag returned to the South. But after 148 years, his wish has been honored.

The Union officer's great-grandson, Robert Clayton, donated the flag to be displayed at Fort McAllister State Historic Park in coastal Georgia, where a dedication is planned next month just before Confederate Memorial Day. Clayton suspects his ancestor wanted to pay back his former enemies after a Bible taken from him by Confederate troops during the war was returned to him by mail 63 years later.

"I think he had a little sympathy for the plight of the Confederates," said Clayton, a homebuilder who lives in Islesboro, Maine. "They returned his Bible, so he wanted to return their flag. One good turn deserves another."

With its canons pointed out over the Ogeechee River a few miles south of Savannah, Fort McAllister was where Sherman won the final battle of his devastating march to the sea that followed the burning of Atlanta. The Union general knew that taking the fort would clear the way for him to capture Savannah. On Dec. 13, 1864, he sent about 4,000 troops to overwhelm Fort McAllister's small contingent of 230 Confederate defenders.

Among the Confederate units defeated at the fort was 2nd Company B of the 1st Georgia Regulars, a Savannah-based outfit otherwise known as the Emmett Rifles. The company's commander, Maj. George Anderson, surrendered his unit's ceremonial flag after Fort McAllister fell.

Decades later, the flag's capture was no secret to Daniel Brown, the park manager at Fort McAllister, who kept research files on the Emmett Rifles banner and four others known to have been taken by Union troops under Sherman. He called the flag a "once in a lifetime" find, especially considering that Civil War sites nationwide are still marking the 150th anniversaries of the war's battles and events.

"You can't put a price on it," said Brown, who put the flag on display last month. "Everybody has drooled over the thing."

Brown was well-versed in the flag's history during the war, but clueless as to what had become of it since.

That changed when Robert Clayton paid a visit to the Georgia state park during a vacation in October 2010. He struck up a casual conversation with Brown about the Emmett Rifles.

"I said, 'What would you say if I told you I had the Emmett Rifles flag hanging on my living room wall?"' Clayton recalled.

Clayton had found the flag, and its note with his great-grandfather's wish, about 20 years earlier stashed in a closet. He said he didn't know why older family members had never returned it, but also admits he wasn't at first eager to part with the flag himself. Instead he framed the banner and displayed it in his home.

Clayton said his visit to Fort McAllister made him change his mind. Before he left Georgia, he had agreed to donate the flag and follow through on his great-grandfather's written request. But it took months to make the final exchange -- mostly, Clayton says, because he couldn't work up the nerve to mail the flag 1,230 miles from Maine to Georgia. When he finally shipped it for overnight delivery last summer, he stayed up tracking the package online until it arrived.

Once the flag arrived in Georgia, park rangers turned it over to conservation experts who mounted and sealed it in a protective frame. Park staffers finally hung it above a display at Fort McAllister's museum last month.

Brown said he had some doubts when he first heard Clayton's story, but once he saw the flag he could quickly tell it was authentic. The dates of two prior battles in which the Emmett Rifles fought at Fort McAllister -- Feb. 1 and March 3, 1863 -- were also painted on the silk. Brown had records of the military orders authorizing the unit to add those specific dates as honors to its flag.

His files also confirmed that historians had identified the Union officer who captured the flag in 1864 as Maj. Clayton, the donor's great-grandfather.

Civil War flag experts say the Confederate banner is a remarkable specimen that was hand-sewn from pieces of silk with a fancy golden fringe.

There's one small tear and the red field has faded almost to pink, but its blue "X" and white stars remain crisp. So do the hand-painted words -- "Emmett Rifles" and "Fort McAllister" -- and battle honors.

"It's a terrific find," said Cathy Wright, a curator and flag expert at the Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond, Va., which has a collection of about 550 Civil War flags. "It's not one-of-a-kind, but it's a relatively rare example of this kind of flag."

Despite orders after the Civil War to turn all captured flags over to the federal War Department, many Union troops kept them as souvenirs.

Many other unit flags were destroyed during the war, either by capturing units cutting them into pieces to divide the spoils or by units burning their own flags to stop them from falling into enemy hands, said Bryan Guerrisi, education coordinator at the National Civil War Museum in Harrisburg, Penn.

"A lot of them get lost or are in somebody's attic and they think it's a blanket or something," Guerrisi said.

In 1905, under orders from Congress, the federal government began returning its stash of captured Confederate flags to the Southern states -- a move aimed at reconciliation that provided museums with many of the flags in their collections.

Clayton is planning to travel back to Fort McAllister to see his great-grandfather's flag officially unveiled to the public April 21, two days before Georgia celebrates Confederate Memorial Day.

"It was my great-grandfather's wish," Clayton said. "I looked at it for 20 years, but it needed to go back where it belongs."