Columbine shooting survivors and the families of those who died say the upcoming 20th anniversary of the massacre is conjuring up feelings of pain, hope, love and despair – on top of their concerns of the unexpected as they watch their own children head off to school each day.

The attack on April 20, 1999, in Littleton, Colorado, forever changed the debate about gun violence in American schools. Now two decades later, the children of Dave Sanders -- the lone teacher who died in the shootings at Columbine High School – say strangers still come up to them to thank them for their father’s heroics that day. Sanders has been credited with leading dozens to students to safety before succumbing to his wounds.

“I run into kids who had him as a teacher, and one of them said, 'Can I take a picture of you holding my child?' And I said, 'Why?' And they said, 'Because he wouldn't be here without your dad,’” Coni Sanders told Fox31 in an interview this week.

“And so we're seeing these generations of kids who had a chance to grow up to be adults and parents and grandparents [because of my dad],” she added. “My sisters and I are so proud.”

WOMAN ‘INFATUATED’ WITH COLUMBINE, CONNECTED TO COLORADO SCHOOL THREATS FOUND DEAD

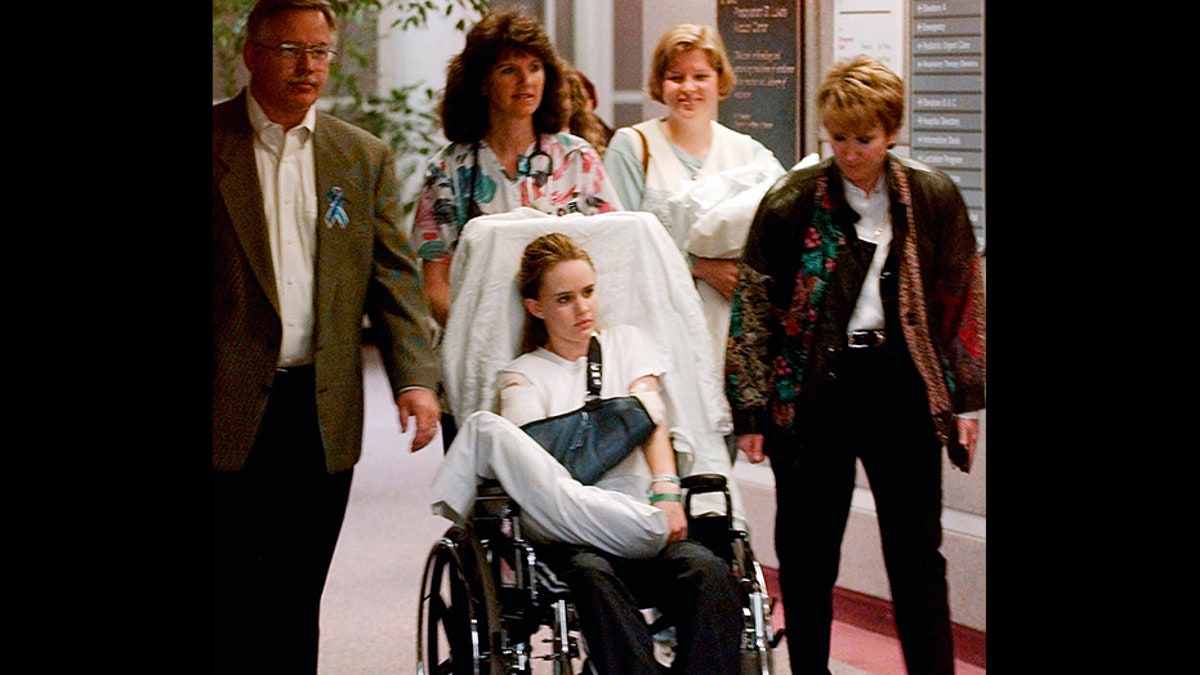

Kacey Ruegsegger, 17, is wheeled from a Denver hospital by Patty Anderson, center, after being released in May 1999. Walking beside her are her parents Greg, left, and Darcy, right. Ruegsegger Johnson survived a shotgun blast during the shootings at Colorado's Columbine High School that left 12 students, one teacher, and both gunmen dead. (AP/File)

For survivors like Kacey Ruegsegger Johnson though, the emotional toll remains heavy as she lives out her life post-Columbine and watches her four children grow up. For the last 20 years, she has lived with post-traumatic stress disorder, along with physical pain. She worked as a nurse until the injuries to her arm – caused by a shotgun blast to her right shoulder during the massacre -- forced her to stop.

“I’m grateful I have the chance to be a mom. I know some of my classmates weren’t given that opportunity,” Ruegsegger Johnson told the Associated Press, with tears in her eyes. “There are parts of the world I wish our kids never had to know about. I wish that there would never be a day I had to tell them the things I’ve been through.”

In an interview with the news agency published this week, Ruegsegger Johnson revealed how she would cry most mornings as her children left her car, and that she relied on texted photos from their teachers to make it through the day.

TEEN BOYS UNLEASHED TERROR, CHAOS AT COLUMBINE

On a recent sunny spring morning, she helped her kids find their book bags and tie their shoes before ushering them to her car. She prayed aloud as they neared the school, giving thanks for a beautiful morning and asking for a day of learning and friendship. And as always, the Associated Press says, she made a silent addition: Keep them safe.

Amy Over, who escaped the cafeteria at Columbine during the mass shooting, says she saw Sanders in the last hours of his life. She suffered no physical injuries from the attack, but has struggled emotionally for years.

Over told the Associated Press that waving goodbye to her daughter on the first day of preschool triggered a panic attack — the first of many. She was diagnosed with chronic panic disorder, underwent therapy and found new strategies for her life as a mother of two.

She now coaches her 13-year-old daughter Brie when she ventures to places outside her mom’s control: Where is the closest exit? What street are you on? Who is around you?

“I never want my kids to feel an ounce of pain, the way that I felt pain,” Over said. “I know that that’s something that I can’t control. And I think that’s hard on me.”

Members of a police SWAT team march to Columbine High School on April 20, 1999. (AP/File)

Over says she first told Brie about her experience at Columbine two years ago, a few days before the anniversary.

That April 20, they visited the school for a memorial ceremony that included a reading of the names of the 13 people killed. Afterward, the Overs walked together through the quiet school.

Over told the Associated Press that opening up to her daughter was cathartic and so they have continued to attend annual memorial events, now imbued with a gentler tone with the girl by her side.

“It’s a day of reflection,” Over said. “It’s a day of love and hope. And I get to share that with my daughter.”

Frank DeAngelis, the principal of Columbine when the shooting happened, told CBS News in a recent interview that he starts his days reflecting on the 13 who were killed in the attack.

“Every morning when I wake up, as soon as I get out of bed I recite the names of my beloved 13," he said. "I’ve done it since the shootings happened and they are not with us physically but spiritually, they’re with me every day.”

Michelle Wheeler, another survivor who appeared alongside him and now teaches middle school English in Columbine's district, said she has given up on trying to figure out why the "broken souls" behind the attack carried it out.

"I’ve forgiven them. I think they lost their lives way before the 20th," she said. “There is nothing I would get out of knowing why."

Kacey Ruegsegger Johnson poses for a portrait at her home in Cary, N.C., in late March. (AP)

Wheeler also said wherever she goes with her daughter, she is on alert for potential escape routes.

“We’ll be in the doctor’s office… and I’ll say ‘show me five places where you’ll hide’," she told CBS News. "Because it could happen anywhere and I want her to be prepared. And I think it makes me feel prepared.”

“We’ll be in the doctor’s office… and I’ll say ‘show me five places where you’ll hide... Because it could happen anywhere and I want her to be prepared. And I think it makes me feel prepared.”

Austin Eubanks, who survived being shot in the Columbine library, is among those who doesn’t fear the schools his sons, ages 13 and 9, attend.

Instead, he laments that active-shooter drills, video surveillance and armed guards are all too routine for them — as natural as a tornado drill was for him growing up in Oklahoma.

“We are so unwilling to actually make meaningful progress on eradicating the issue,” said Eubanks, who remains scarred by watching his best friend, Corey DePooter, die. “So we’re just going to focus on teaching kids to hide better, regardless of the emotional impact that that bears on their life. To me, that’s pretty sad.”

Isolation, depression, addiction and suicide are among the larger dangers he sees facing his kids’ generation, and he knows firsthand the damage those can cause.

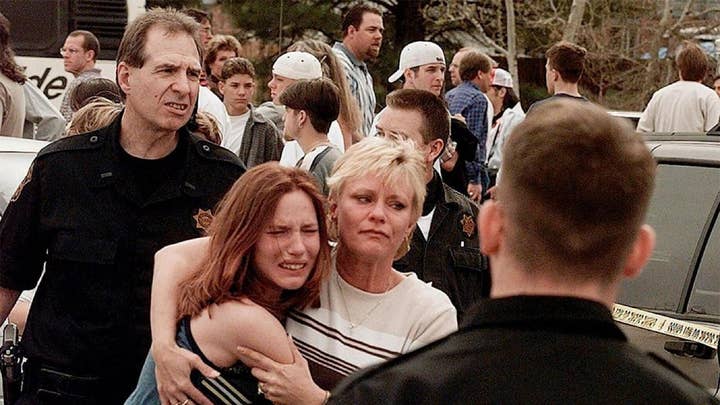

A woman embraces her daughter after they were reunited following the Columbine High School shooting. (AP/File)

For more than a decade after the attack, Eubanks was addicted to prescription pain medication, according to the Associated Press. He got sober in 2011 and began repairing his family, including his relationship with his sons and their mother. He now works at an addiction treatment facility and travels the country telling his story.

At home in Colorado, he tries to help his sons become attuned to pain others may be feeling. He encourages them to talk to an adult when peers seem so angry or afraid that they may need help. He tries to remember that — for them — all of the changes in schools are just normal.

He was horrified by videos that Marjory Stoneman Douglas students shot in Parkland, Florida, last year as they hid inside a classroom while a gunman moved through the halls of the high school. He has urged his own boys to always try to escape first — whatever it takes — even if school safety drills advise staying put.

“These are my children, and what I care about most is their safety,” he said. “And I know that for them, in a situation like that, getting away from it as quickly as possible is the best likelihood of success.”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

And he still honors DePooter when going fly-fishing in the wilderness, according to Fox31.

“When I'm out there and I catch a fish that's of above-average size, I kind of give him a nod and say, you know, 'He was with me today,'” Eubanks told the station.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.