Fox News Flash top headlines for August 23

Fox News Flash top headlines for August 23 are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com

There are more than 750,000 registered sex offenders across the country and, medical professionals explain, faith and community are often deemed a crucial part of their treatment to avoid re-offending.

Despite that more than half of those cases – at least 400,000 – involve children, many offenders slip under the radar and end up on voluntary leadership roles unnoticed, background check experts warn.

“Churches rely heavily on volunteers who work with youth and children,” Josh Weis, executive vice president at Ministry Brands, a provider of church management software and screening products for more than 115,000 churches and organizations to provide services such as background checking software, told Fox News.

“Criminals are often very crafty and see churches as a soft target.”

“We’re happy to be seeing more churches run background checks, but most are only running the minimum of what is required. It gives a false sense of security, and it isn’t enough,” he said.

A recent Ministry Brands audit of tens of thousands of churches nationwide found that although the number of churches conducting background checks grew at least 12 percent over the past year — an estimated 60 percent of churches and ministries don’t opt for the broader options.

Under federal law, employers must notify job or volunteer applicants if they plan to run a background check on an applicant. (AP)

“Basic background checks are not enough to keep dangerous predators from taking positions as religious leaders, and the first step in safeguarding children is through a more thorough screening and re-screening policies,” Weis stated. “Checking a single name or simply running an applicant through a criminal database is not enough. Depending on the state, these lower-level screens can be equivalent to merely Googling a name.”

Indeed, one recent example of a bad actor going undiscovered is that of Florida minister – and registered sex offender – Charles Andrews.

Late last month, Sarasota County police arrested the 66-year-old and charged him with 500 felony counts of possession of child pornography and three counts of failing to meet sex offender requirements, following up on a tip from the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

Late last month, Sarasota County police arrested Charles Andrews, 66, and charged him with 500 felony counts of possession of child pornography.. (Sarasota County Jail)

Andrews, who was a pastor at Osprey Church of Christ, had been convicted in 2006 of second-degree sexual abuse in Alabama and registered as a sex offender in both states. The Florida registry lists Andrews as still being behind bars in county jail, while the Alabama sex offender registry website didn’t seem to work at all.

A representative did not immediately respond to a request for comment as to why the site had a continual “server error.”

“The reality is that both the National Sex Offender Registry and the National Criminal Database searches are not updated in real-time," said Weis. "An even lesser-known fact is that in 50 percent of America, the most critical or real-time data comes directly from counties and requires a deeper background search.”

Thus, he emphasized, churches need to turn to more systematic and thorough checks and not rest on the laurels of the cheap and basic ones offered online.

But there are glaring loopholes. Standard background checks typically sift out the traffic records, credit history, employment verification, criminal records and crucially – the federally-mandated sex offender register in every U.S. state.

However, laws and registry policies differ from state to state.

The Ministry Brands study also found that less than 10 percent of churches are actively rescreening their volunteers and staff annually, a statistic Weis called “alarming.”

NUNS SEXUALLY ABUSING MINORS COULD BECOME NEXT CATHOLIC CHURCH SCANDAL, EXPERTS SAY

A more all-inclusive check, Weis surmised, would involve such processes as routine rescreening at least once a year, conducting further queries on applicants coming from other states and scrutinizing red flags from their previous addresses.

“Typically, you should provide a driver’s license or a passport and a lot of volunteer organizations don’t want to do that because they don’t want to add an extra layer to those seeking to help, but it is important,” Weis continued. “We also emphasize the use of social security numbers, take the data and use it to create common alias or abbreviated names.”

He noted that, according to their checks, between 4 and 10 percent of volunteer applications result in some sort of record worthy of closer scrutiny. An investigation released this year jointly conducted by The Houston Chronicle and the San Antonio Express-News found that almost 400 Southern Baptist leaders either pleaded guilty or were convicted of sex crimes against more than 700 victims between 1998 and 2018.

“Our job is simply to pass the information on to customers – in this case, churches – and it is up to them as to what they want to do with that information. But criminals are often very crafty and see churches as a soft target,” Weis said. “Most sex offenders will take themselves out of the application process once they know a background check will be run, so they are looking for churches that aren’t going to run a check at all.”

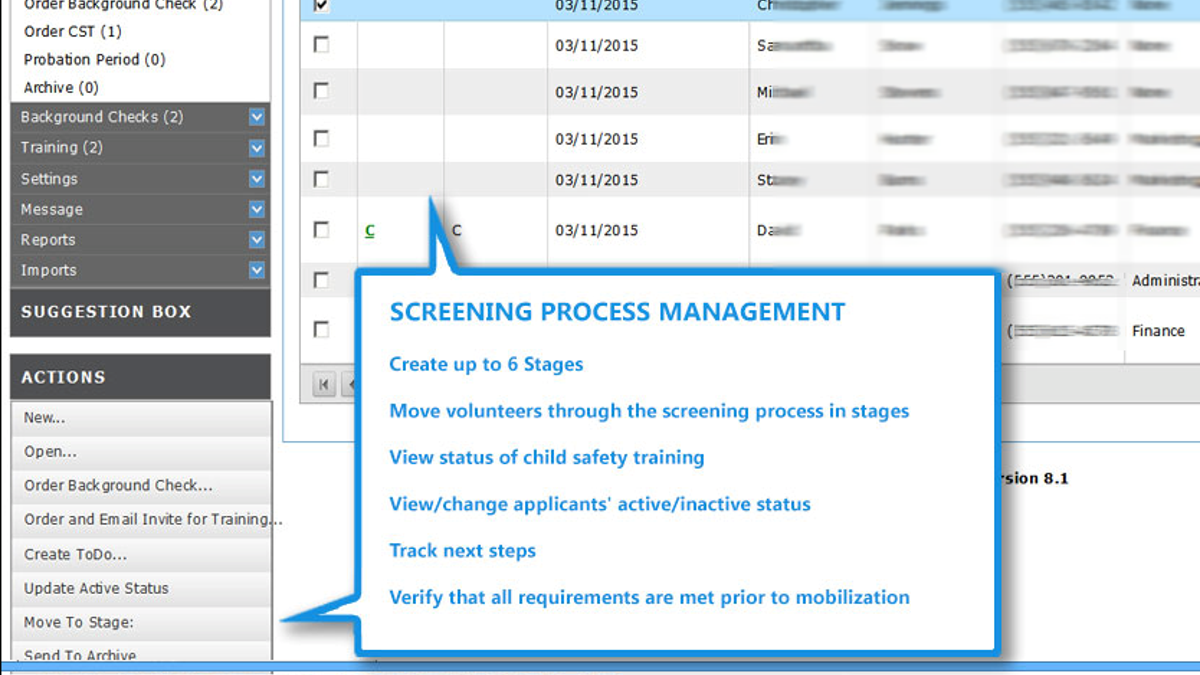

Ministry Brands background check software

David Rogers, Senior Vice President of Marketing at Ministry Brands, also highlighted that a loophole they have encountered is when an offender, even for sex-related violations, pleads down to a misdemeanor and can then skirt the basic background system.

“Even if not a felony it can set off a red flag, so if you don’t run those more complex searches you might not detect what you need to,” he said.

Under federal law, employers must notify job or volunteer applicants if they plan to run a background check on an applicant. This notification must clearly state that the report is for employment purposes, and the notification must relate only to background checks.

So that brings about the broader dilemma many are still grappling with — what about those who just want to attend church, thus are not subject to a formal check?

In June, a registered sex offender – with a proclivity for photographing young victims – was arrested on three counts of production of child pornography and a related sex crime. Lavelle Hinton, 55, had allegedly used an alias name when attending services at a Chesapeake congregation in Virginia. He then lured a 16-year-old girl he met at church to run away with him, after allegedly giving her bottles of alcohol in exchange for bags of cookies.

Hinton, according to the Virginia sex offender registry, was on parole at the time and has an extensive conviction history from Minnesota, including a 1994 conviction for fourth-degree criminal sexual conduct and two more convictions over the proceeding five years for third-degree criminal sexual conduct – all against minors.

For many church attendees and leaders, the concept of welcoming sex offenders to the congregations is a serious test of faith and entails deep questioning as to whether doors are truly welcome to all – or whether the risk to simply too high.

Some contend that it's critical to the healing process, others argue that sex offenders will sometimes display a tendency to exploit Christianity’s central tenants of forgiveness.

“One of the challenges for all organizations who serve children and youth is that an offender who acts in a predatory manner may find one church who faithfully lives into Safe Sanctuaries policies and guidelines, and move on from that church to another that may not be as compliant,” observed Kevin Johnson, Director of Children’s Ministries at Discipleship Ministries of The United Methodist Church.

Sex offenders are not generally banned from churches, but the law varies state to state and enforcement can vary county to county.

AFTER EPSTEIN DEATH, GLARING LOOPHOLES IN NATIONAL SEX OFFENDER REGISTRY RAISE CONCERNS

Laws that have endeavored to ban offenders from houses of worship have faced legal challenges, both under their constitutionality generally and also the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA).

"Churches need to recognize that abuse is not an isolated risk in a far-off place — abuse can happen anywhere. Taking this seriously is the first step,” said Travis Wussow, vice president and general counsel of the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission (ERLC), an entity of the Southern Baptist Convention. “This is one of the reasons the ERLC devoted nearly the entire last year through today working with child protection experts, law enforcement officials, lawyers with experience in these cases, and church leaders to produce guides, curriculum, and resources in response to this crisis.”

Pope Francis, talks with the head of a sex abuse advisory commission, Cardinal Sean Patrick O'Malley, of Boston, as they arrive for a special consistory in the Synod hall at the Vatican on Feb. 13, 2015. (The Associated Press)

As far as attendance goes, insurance companies typically advise ministries to examine each case on an individual basis, seek legal counsel, develop a covenant with the offender and determine who in the church community needs to know about one’s illicit history.

“The risk of sexual abuse is real. If your organization serves children and youth, you have a responsibility to provide a standard of care for those most vulnerable. It is imperative that you evaluate your current preventative measures,” Rich Poirier, president and CEO of Church Mutual Insurance Company, pointed out.

The firm recommends that all those involved in children’s programs hold training on child sexual abuse laws, organizational policies and education on how to recognize the “grooming process” used by sex offenders to gain the trust of their victims.

Nonetheless, some churches have taken explicit efforts to open their arms to sex offenders.

The Sonrise Church in Hillsboro, Ore., since 2002 has been holding “Light My Way” services every Sunday afternoon – beginning with a meal and followed by worship – for sex offenders. Around 150 attend the service on average every week, around six to percent are sex offenders.

“I started hearing about how sex offenders who wanted to go to church had doors shut in their face and I wanted to start a service that welcomed all ex-cons. I had to work with the local sheriff and district attorney and set standards and rules, and they wanted to get behind it,” added James Gleason, lead pastor at Sonrise. “The neighborhoods haven’t seen it that way – there has been a lot of conflict mediation. But not a single attendee has re-offended. It’s a safe space from isolation, and into the light.”