Nearly 75 years after the Japanese military forced American prisoners of war to “march” 65 miles through the Philippine jungles, eight survivors of the infamous Bataan Death March are gathering in New Mexico with thousands of others to memorialize the atrocity.

Besides the eight survivors, more than 7,000 athletes and supporters this weekend will also gather in the New Mexico desert to participate in the 27th annual Bataan Memorial Death March.

The event is one of several taking place over the next month to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the Bataan Death March, one of World War II’s greatest atrocities.

“It is particularly significant this year because very few people actually know the story of Bataan and being the 75th anniversary, there are very few survivors left to tell the story. This could be one of the last times that the community can honor these men and recognize their bravery,” says Lyn Rolf III, director of programs at the Veterans of Foreign Wars.

Of the 10,000 Americans who endured starvation and torture in 100-degree temperatures, fewer than 50 survivors are alive today.

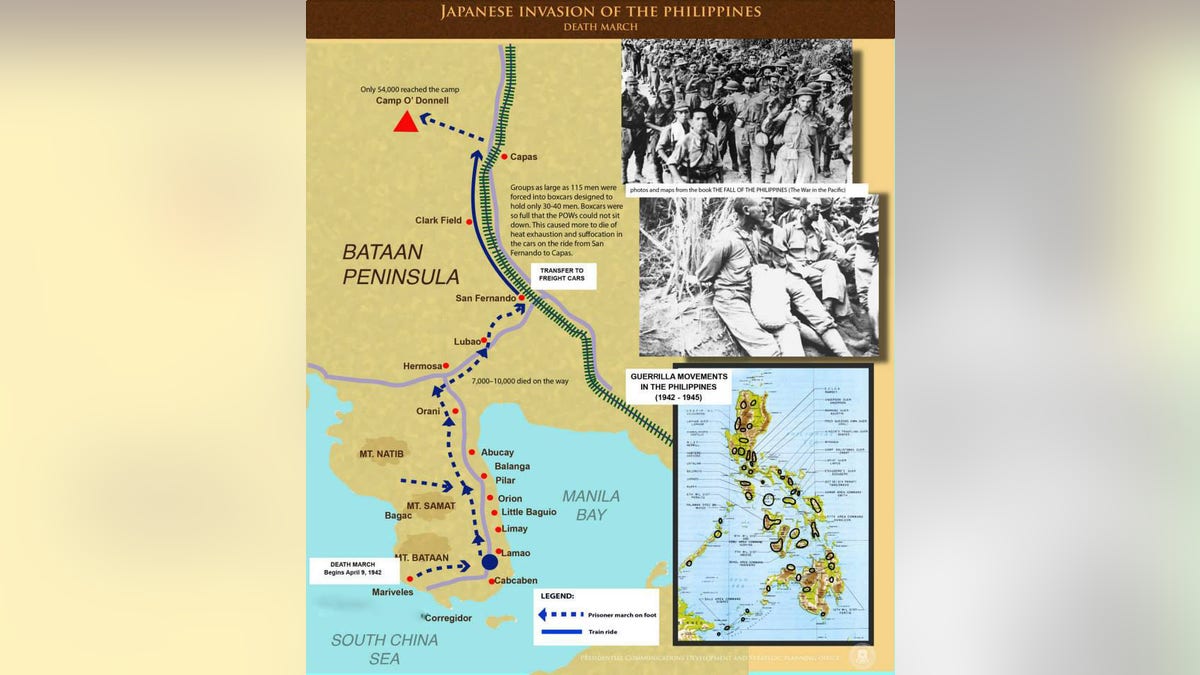

The story of Bataan began hours after the Dec. 7, 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor when Japan launched an assault on several islands in the Pacific, including the Philippines. Despite a lack of naval and air support, 75,000 American and Filipino forces held off the invading Japanese troops until they were eventually forced to retreat to the Bataan Peninsula.

On April 9, 1942, U.S. Gen. Edward King Jr. surrendered to Japanese forces, who would soon show they had no intention in honoring the Geneva Convention.

Over eight days, the Allied forces made their way from Mariveles, on the southern end of the Bataan Peninsula, to San Fernando.

While no definitive numbers are available, historians estimate that 1,000 Americans perished while 5,000 and 10,000 of a total 65,000 Filipinos soldiers succumbed to the harsh conditions or were killed by their Japanese captors.

The survivors would spend the next three years in captivity in the Philippines or in Japanese POW camps, an experience that forged intense bonds among the men.

“It brings great satisfaction to me personally and makes me feel I have done my duty for those special men who are not here today,” says Ben Skardon, a 99-year old Bataan survivor who will make his 10th trip to the White Sands Missile Range to walk 8 ½ miles on Sunday.

“If you knew about the sacrifices of those men in the prison camps, you would know I am the weak one. They brought me back, time and again, from death and they are so much of a part of my years in incarceration that I cannot ever forget them,” adds the Army veteran who will celebrate his 100th birthday in July.

Before his capture, Skardon earned two Silver Stars and four Bronze Stars for valor while leading Company A of the 92nd Infantry Regiment PA (Philippine Army), a battalion of Filipino Army recruits.

According to the U.S. Army Center of Military History, American government and military officials first learned of the Bataan Death March in the summer of 1943 from an officer who escaped from a prison camp. On April 3, 1946, General Masaharu Homma, the commanding general of the Japanese Army during the Bataan Death March, was executed.

While the surrender of Allied forces was a military defeat, the stubborn defense of the Bataan Peninsula was a key victory that showed the Japanese were not an invincible force.

“It was perhaps the second most consequential event of World War II after Pearl Harbor, but even the people in the Philippines do not know the history of the Bataan. It is so important to educate people about Bataan and to honor those who survived,” says Robert Hansen, a member of the board of directors of the Bataan Legacy Historical Society and the grandson of a Bataan survivor. http://www.bataanlegacy.org/index.html

Hansen tells Fox News his family members talked about their experiences during the war, but never mentioned Bataan.

“It was only through doing outside research that I learned my grandfather was on the march. They didn’t talk about it because of the bad memories it brought back,” says Hansen, a retired U.S. Navy senior chief mass communications specialist.

The Historical Society will hold a wreath-laying ceremony in San Francisco next month as part of its efforts to honor and inform the public about Bataan and the role of the Filipinos who fought alongside Americans in the Pacific.

The story of the Bataan survivors carries special importance in New Mexico, home of the Army’s 200th and 515th regiments, which sent 1,800 men to the Philippines.

Only 987 soldiers made it home after being liberated from prison camps, according to Jennifer Talhelm, communications director for Sen. Tom Udall.

The New Mexican Democrat has been working for years to award Congressional Gold Medals to the survivors and plans to reintroduce his bill supporting that recognition soon.

Many believe it is the least the nation can do for them.

“Their hearts and their sheer unwillingness to give up even while hundreds of their friends died alongside them on the march. If anything, that is the American spirit right there,” says Rolf.