SUMNER, Miss. – The federal government has reopened its investigation of the 1955 slaying of black teen Emmett Till, a case that helped build momentum for the civil rights movement. The move comes a year after a book on the case revealed that a key figure acknowledged lying.

The Associated Press is republishing a version of a report that followed the acquittal of the two men in the Till case. The following AP story is from September 1955.

___

An all-white jury, composed mainly of Delta cotton farmers, acquitted two white storekeepers of the murder of a 14-year-old Chicago Negro boy yesterday, but the half-brother spent the night in the county jail.

Roy Bryant, 24, and John Milam, 36, still face charges of kidnapping Emmett Louis Till from the sharecropper shack in Leflore County where he was vacationing with his uncle, Mose Wright.

The two men were tried in Tallahatchie County because a battered, bullet pierced body — buried as Till's, but later rejected by the jury — was fished from the muddy Tallahatchie River inside the county line.

Jury foreman J.A. Shaw said identification of the body was the deciding factor in the one hour and seven minute deliberation that resulted in an innocent verdict on the third ballot.

"The verdict is as shameful as it is shocking," said the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People in a statement from its New York headquarters. "The jurors who returned it deserve a medal from the Kremlin for meritorious service in communism's war against democracy."

Bryant and Milam spent the night in the Leflore County Jail in Greenwood when their attorneys conferred with the state officers over the amount of bond needed for their release under the kidnap charge.

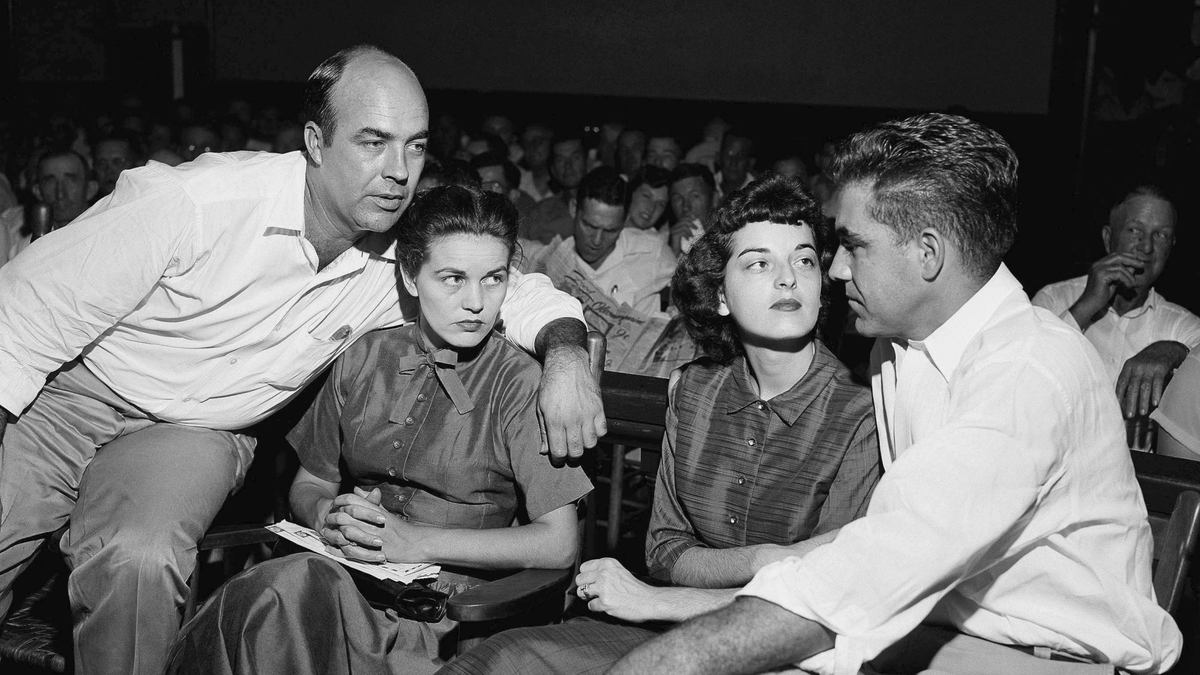

They were taken back into custody a few minutes after they embraced their wives happily as Shaw intoned: "We, the jury, find the defendants not guilty."

Both men accepted the verdict gladly, as did the spectators who jammed into the muggy courtroom. Except for one loud exclamation, there was no demonstration.

The quiet announcement came as an anti-climax to the rising oratory of summing up arguments that held jury and audience in rapt attention.

Shaw first simply said, "not guilty," but Circuit Judge Curtis Swango, Jr., who won praise from the NAACP for his handling of the trial, sent him back to try again in proper legal language.

Mrs. Bryant, the pretty mother of two boys, who testified a Negro man molested her on Aug. 24, said with a relieved smile: "I'm very happy. I feel a lot better than I did yesterday on the witness stand."

Before the trial, officers said the 21-year-old woman was the object of Till's wolf whistle. But on the stand, as a defense witness, she mentioned no names in relating the episode at the store. Her husband's attorneys used this lack of identification to demand of the state: "Where's the motive?"

Part of her testimony was witnessed from the jury and she was never cross examined.

Two officers corroborated Wright's testimony that Bryant and Milam abducted Till from the sharecropper shack near the little Delta town of Money where Bryant runs a general store. The officers said the men admitted it in pre-trial questioning.

The storekeepers did not testify in their defense, but before the trial they claimed to have released Till unharmed because Mrs. Bryant said he was not the Negro who grabbed her around the waist and made an indecent proposal.

The state built its case around eye witnesses, like the 63-year-old Wright, to the pre-dawn abduction and around the testimony of a 13-year-old Negro boy who said he heard "licks and hollering" coming from a barn owned by Milam's brother in Sumner County.

Shaw said the jury ignored the boy's testimony and was unimpressed with the appearance of Mrs. Mamie Bradley, Till's widowed mother, who came down from Chicago and tearfully insisted the body was her son's.

"There was a reasonable doubt," said the jury foreman about the identification of the body.

The defense offered no evidence to counteract the kidnap testimony, beyond questioning Wright's ability to recognize faces in the pre-dawn darkness with a flashlight shining in his face.

Instead, it concentrated on raising doubts about the identification of the body that floated up in drift in the murky river, focusing on the simple theory of no body, no murder.

A sheriff, a doctor and an undertaker testified the body they saw was in advanced state of decomposition and may have been dead anywhere from eight to 25 days. The time element was important here. Only three days elapsed from the time Till was taken out into the Delta darkness and a teen-aged fisherman sighted the dead body, weighted with a 70-pound cotton gin fan tied around the neck with barbed wire.

A ring on one of the bloated fingers bore the initials "L. T." Mrs. Bradley said it was her husband's, and the boy had put it on before catching the train for his vacation in the south.

The defense handled this by hinting that anti-segregation groups were "capable of anything" in attempting to destroy the southern way of life.

The first jury ballot showed nine of the 12 for acquittal, with three undecided. On the next ballot, one more came out for acquittal. The third ballot was unanimous.

Dist. Atty. Gerald Chatham had no quarrel with the verdict.

"The right of trial by jury," he said, "Is a sacred guarantee of the United States Constitution. I accept it and stand by it." He did not elaborate.

At the all-Negro town of Mound Bayou, Miss., Mrs. Bradley said she left before the jury came in — "I was expecting an acquittal and I didn't want to be there when it happened."

She was accompanied by Rep. Charles Diggs, a Negro congressman from Michigan who attended the trial. Like the NAACP, Diggs praised the judge and prosecution but sharply criticized the defense witnesses and the jury.

The boy's mother said she was "a little amazed" by the brevity of the jury session.

The verdict still left unanswered the question of what happened to Till. If the body floated up by the river was not his, then where is he? And who was the body found in the river?

Sheriff H. C. Strider of Tallahatchie County said he would combine his investigation in an attempt to identify the body.

Dist. Atty. Stanny Sanders of Leflore County said he would seek a kidnap indictment at the November session of the Grand Jury.

The men were indicted for kidnapping by a Tallahatchie County Grand Jury, but Judge Swango dropped the charge at the request of Chatham when the neighboring county took jurisdiction.

The charge carries a maximum penalty of 10 years.