For 70 years Glenn Lane eagerly shared his memories of the Japanese ambush on Pearl Harbor with friends, family, schoolchildren and anyone else who wanted to hear the tale of how he survived attacks on two battleships that fateful day.

"He loved to share his story and he remembered every minute detail as if it happened yesterday," Lane's youngest daughter, Trish Anderson, recently recalled.

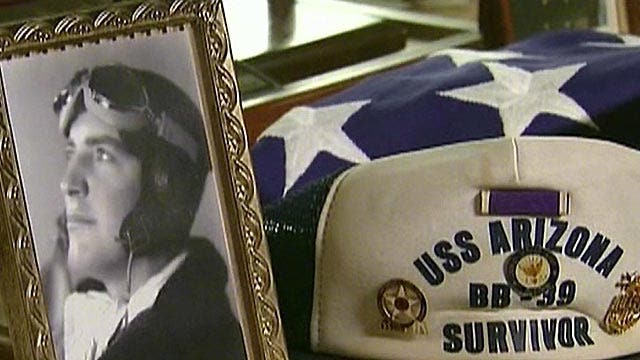

Today's anniversary of the surprise attack that pushed the United States into World War II is the first since Lane died a few days after the 2011 remembrance. But Lane and his connection to the famed U.S.S. Arizona are permanently enshrined on the ship and the memorial that sits in the waters of Pearl Harbor.

"He never called himself a hero," Anderson said. "People would always go, 'oh, you're such a hero.' And he said, 'no, the heroes are still down in the ship.'"

Today, that ship also includes Lane, who in September was interred in the Arizona's number four gun turret. He is at rest with the sailors who died during the attack and 35 others survivors who like Lane asked to be reunited eternally with their shipmates. His name is now inscribed in the memorial’s white marble.

Lane was born in 1918 and grew up on farms in Iowa and Minnesota. Seeking adventure away from that simple but rugged life he joined the Civilian Conservation Corps and worked on the Grand Coulee Dam. In 1940, Lane and his buddies saw the growing conflict in Europe and figured the United States would soon be involved. They decided life in the Navy would be a lot safer and enlisted. Lane was soon stationed on the Arizona.

In December 1941, the radioman third class worked as a scout in the backseat of a two man airplane. On the morning of the 7th, Lane was about to take a shower when he heard the roar of explosions outside. Anderson says, "he tried to tell some of his friends and they were, 'ole Lane, you always tell these April Fools' jokes. Get out of here.' And he said, 'this is no April Fools' joke, buddy, look out the window.'"

In the confusion of the moment Lane wasn't initially pressed into action but soon was ordered to report to the ship's deck. While still working his way up a staircase, a Marine lieutenant tried to stop him but Lane quickly and forcefully brushed past to make his way outside. Many of the men left behind below deck would die in the attack. It wouldn't be the first time that day that fate steered Lane to safety.

While engaged in a futile attempt to extinguish the tremendous flames, Lane was sent flying overboard when a crippling explosion rocked the front of the ship. Now treading in the oil-slicked waters, Lane saw no signs of hope in returning to the Arizona. Instead, he found a small barge and steered toward the U.S.S. Nevada which was moving to escape the attack.

Once on that ship, Lane tried to enter a munitions room called a casemate but was turned away because he was drenched in oil. Other sailors nearby were more welcoming and Lane was able to take shelter. A bomb eventually ripped through that first casemate killing all of the men inside.

"He's the only guy that we know of in history that was on two battleships on Dec. 7th," Anderson said. "And I remember asking him one day why he swam to the Nevada when the other guys swam to Ford Island. And about four hours later he was almost through telling me the story."

After the attack, Lane spent 10 days on another naval ship recovering from his wounds. He was soon reassigned to the ill-fated U.S.S. Yorktown. The carrier was crippled during the battle of Coral Sea then Japanese planes sunk it at Midway. After the war, Lane remained in the Navy and flew missions as part of the Berlin Airlift and spent time in Vietnam. He retired after 30 years service and never tired of talking about the Pearl Harbor attack.

On a windy September afternoon, Anderson and other members of Lane's family went to Hawaii for a ceremony on the Arizona memorial complete with a 21 gun salute, playing of Taps and a military flyover. Lane's urn, made by his son Tom, was brought into the water by National Park Service and Navy divers and placed inside the turret not far from where Lane last stood on the ship.

"He just always felt like he wanted to have his final resting place be with his shipmates on the Arizona," Anderson said.