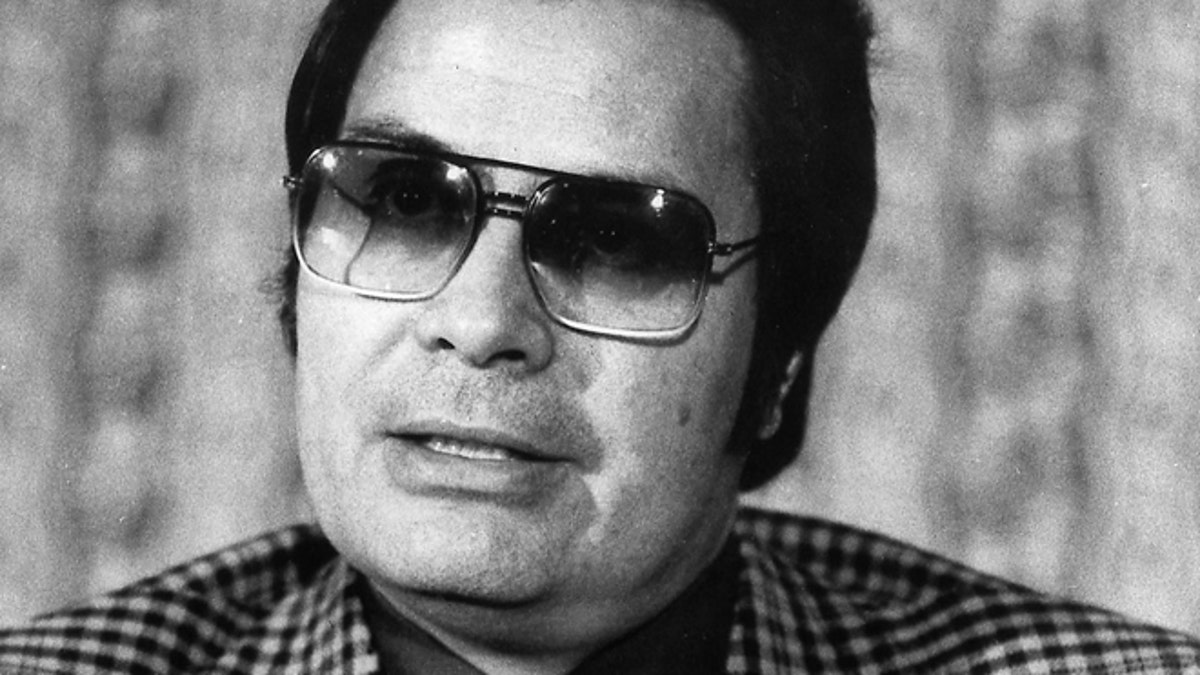

This Jan. 1976 photo shows the Rev. Jim Jones, pastor of peoples Temple in San Francisco. (AP)

DOVER, Del. – Thirty-five years ago, funeral directors in Delaware struggled to quickly bury and cremate the remains of more than 900 people who died in a suicide-murder in Jonestown, Guyana, many of them Peoples Temple followers who drank cyanide-laced punch.

Some bodies that arrived back in the U.S. at Dover Air Force Base in 1978 were claimed by families. Some were cremated. Others were buried in a mass grave in California.

On Thursday, officials revealed that not all had been brought to a final resting place. The cremated remains of nine Jonestown victims were discovered in a decrepit, now-shuttered funeral home in Dover, officials said. The discovery reopened wounds.

"All the survivors in touch with me are traumatized because that door had been closed," said Jonestown survivor Laura Johnston Kohl, now a retired teacher from San Diego.

"Whatever journey the ashes took in the U.S. is secondary. The first issue is how do we settle it to make sure the ashes are where they belong ... at Evergreen where everybody is," she said, referring to the cemetery that is the site of the mass grave.

Hundreds of children and a U.S. congressman died at Jonestown, and 911 decomposing bodies were brought to Dover Air Force Base, home to the U.S. military's largest mortuary. The base has handled mass casualties of both military personnel and civilians from wars, the Sept. 11 terrorist attack on the Pentagon and the NASA Challenger and Columbia space shuttle missions.

As the bodies were identified, the military asked about a half-dozen local funeral homes to help the families make arrangements.

Last week, though, the ashes of nine victims were found neatly packaged and clearly marked, with the names of the deceased and place of their death included on accompanying death certificates, the Delaware Division of Forensic Science said Thursday. No names were released publicly because relatives hadn't been notified.

"It's just so sad, for me as a survivor," said Yulanda Williams, 58, now a sergeant with the San Francisco Police Department. Williams spent a decade with the Peoples Temple, including three months in Jonestown, named after the group's founder, Jim Jones. She left with her 8-month-old daughter before the massacre.

"You consistently wind up finding yourself trying to heal but having your wounds opened up again when new information is given," she said.

"We would do what they wanted, either cremation or send the bodies back home. Most of them were sent back home," said funeral director William Torbert Sr., 79.

Funeral directors say it is not uncommon for family members to never retrieve cremated remains.

The Jonestown remains were found at the former Minus Funeral Home after the property's current owner, a bank, called, according to Dover police and public records. They also found 24 other containers of marked, identified remains, and five containers of remains they could not immediately identify, said Kimberly Chandler, spokeswoman for the Delaware Division of Forensic Science.

The dilapidated former funeral home in Dover had a padlock on the double front doors. The building showed few signs of its former use, although a floral design was etched in glass panes at the entrance. Dead vines hung from the building's white plaster walls, and cracked windows were repaired with blue tape.

Jones ran the Peoples Temple in San Francisco in the early 1970s. He founded a free health clinic and a drug rehabilitation program, emerging as a political force. But allegations of wrongdoing mounted, and Jones moved the settlement to Guyana, the only English-speaking country in South America. Hundreds of followers moved.

On Nov. 18, 1978, on a remote jungle airstrip, gunmen from the group ambushed and killed U.S. Rep. Leo Ryan of California, three newsmen and a defector from the group. All were visiting Jonestown on a fact-finding mission to investigate reports of abuses of members.

Jones then orchestrated a ritual of mass murder and suicide at the group's nearby agricultural commune, ordering followers to drink cyanide-laced grape punch. Most complied, although survivors described some people being shot, injected with poison, or forced to drink the deadly beverage when they tried to resist.

Many of the bodies were decomposed and could not be identified. Several cemeteries refused to take them until the Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland, California, stepped forward in 1979 and accepted 409 bodies.

The remaining victims were cremated or buried in family cemeteries over the period of several months following the massacre.