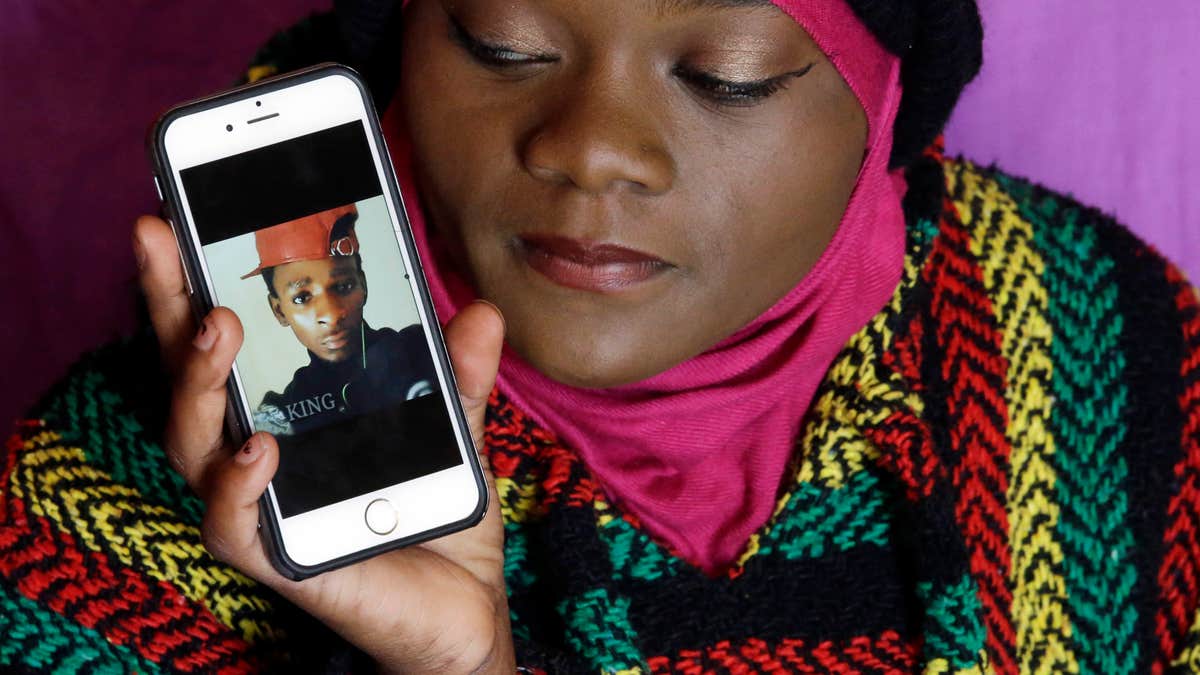

Abdi Mohamed's cousin Muslima Weledi holds a photograph of him during a interview Thursday, March 3, 2016, Salt Lake City. (AP)

SALT LAKE CITY – A 17-year-old Somali refugee critically wounded in a high-profile police shooting in Utah fled to the U.S. from a refugee camp where food was scarce, scorpions scurried everywhere and a toilet was a hole in the ground.

Abdi Mohamed's family settled in Salt Lake City, hoping for a better life.

But things took a turn and he began to get in trouble with police after his beloved grandfather suffered a brain injury in a car accident, his cousin Muslima Weledi said.

She remembered the family's hopeful journey from a makeshift home with sand walls at a refugee camp in Kenya to Utah where the teenager is now hospitalized — and at the center of the latest flashpoint in the nation's discussion about police use of force against minorities. Police have said that Mohamed was shot when he would not obey commands to drop a metal stick being used to beat a man.

It was near-constant violence in Somali that drove the family to flee to the refugee camp, Weledi said. There, they lived in homes with a single bed, cracking sand walls and metal roofs that would fly off with the wind, she said.

"You're pretty much fighting for survival," Weledi said. "We actually came to America to have better life."

The families arrived in Salt Lake City In 2004 when she was 5 and Mohamed was 6. There she saw grass and snow for the first time.

"It was better, because we had water, we had food, we had electricity. We actually had light in the house," she said.

While the young cousins picked up English within a few years, learning a new, written language was more difficult for their parents and making ends meet was sometimes tough. Mohamed's family briefly stayed at a Salt Lake City homeless shelter when money was tight, Weledi said.

In a city that's home to the headquarters for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, their Muslim faith stood out. Weledi remembers classmates staring at her when the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks came up in school.

"They look at us like they're disappointed," she said. "I am Muslim, and I know what we're practicing. It's peace."

The family joined a relatively large refugee population in Salt Lake City, where a healthy economy and Mormon church outreach programs can make it easier for people fleeing war-torn countries to find jobs and transition into life in the U.S.

The cousins made friends, and when they were old enough to work, they helped send money to family back in Africa.

Mohamed's life took a detour after the accident left his grandfather, who was a father figure, unable to remember his grandchildren, Weledi said.

Mohamed started getting in trouble with police at the age of 12, according to court records. He spent time in juvenile detention centers for theft, trespass, and assault, most recently in September.

None of that prepared his family for the news that he'd been shot twice by police.

Police say Mohamed and a second person were beating a man with metal sticks when officers intervened Feb. 27. The officers fired after Mohamed moved menacingly toward the beaten man instead of immediately obeying a command to drop the stick, police said.

But Weledi said she's heard a different version from friends who were at the scene. She said that the man said something that started an argument, and the two were preparing to fight with halves of a broomstick that Mohamed broke when police arrived.

Her cousin's friend Selam Mohammad has said she called his name at the same time the officer shouted for him to drop the stick, so he didn't hear the command.

The shooting touched off unrest in the bustling downtown area not far from the arena where the NBA's Utah Jazz play. The public outcry continued as police refused to release the video until the investigation into the shooting is complete.

Authorities say the video must be viewed in context with other evidence. However, critics point to cases where footage has been released sooner and say the decision highlights inconsistency in how cases are handled.

Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill said in a statement Thursday that releasing the video too early could complicate or compromise his investigation into whether the shooting was justified.

"This investigation — like all officer-involved shooting investigations — is too important to run that risk," Gill said. His investigation could take weeks or months.

But as Mohamed's family waits to see if he'll pull out of a coma, Weledi says the family should know more.

"I think his mom at least deserves to see what actually happened. We're hearing 1,000 different stories," she said. "My cousin had a broomstick and they shot him."