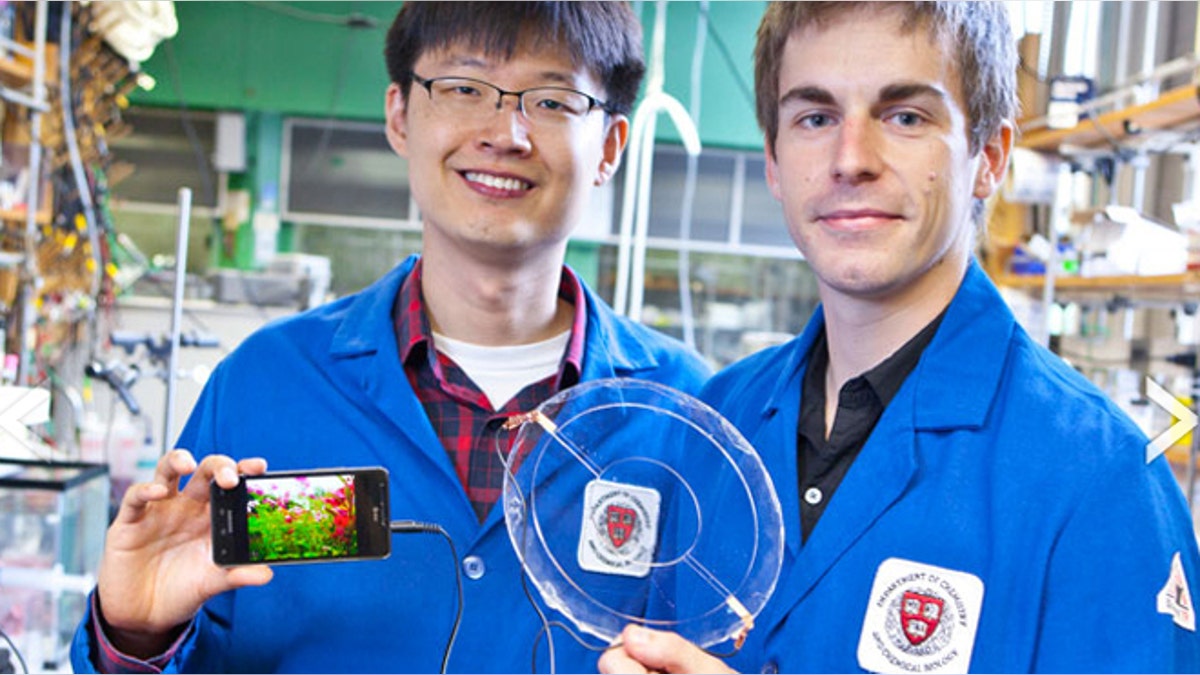

Jeong-Yun Sun (left) and Christoph Keplinger (right) demonstrate their transparent ionic speaker. (Eliza Grinnell/SEAS Communications)

It's a tall order: make a material that conducts electricity, stretches like rubber, expands and contracts when hit with electric current, and is clear as glass. There have been many attempts, but they've all fallen short.

Now a Harvard University team has done it by combining a transparent hydrogel with a conductive polymer that behaves like a motor. The work could lead to artificial muscles, transparent loudspeakers and power sources that generate electricity when squeezed or stretched.

The study, led by Zhigang Suo, professor of mechanics and materials, appears in this week's journal Science.

"Suo and his team combined, in a very clever way, two known things," said John Rogers, a materials science professor at the University of Illinois, who has done extensive work on flexible, implantable devices. "The result -- a transparent, artificial muscle -- is something that is new, and potentially important as a technology for noise cancelling windows, haptic display interfaces, tunable optics and others." Rogers was not involved in this study.

RELATED: New Material Gets Bigger When Squeezed

Stretchable electronics have been made with networks of ultra-thin metal wires, embedding stiff conductive "islands" of electronic components in stretchable sheets, or by using carbon nanotubes. Some research teams have tried mixing polymers with metals. But none of these approaches has been ideal. They are not as flexible or conductive as materials scientists would like.

The Harvard team managed to make a conducting material that stretches as much as good rubber, up to five times its length.

To make the hydrogel, Suo and his colleagues combined a chemical called polyacrylamide with salt water. In the mixture, the polyacrylamide molecules formed a lattice, and the salt ions, which conduct electricity, occupied the open spaces. One surprise was the conductivity -- it was about as good as a typical touch screen. "Typically an ionic conductor like this is several orders of magnitude lower. They were written off as viable conductors," Suo said.

Next, they put a thin layer of the hydrogel, just 100 microns, on both sides of a piece of elastic adhesive mounting tape.

Essentially what they created was a three-layer "sandwich," with the tape serving as an insulating material sandwiched between the two conducting layers of hydrogel. Next, the researchers attached a copper electrode to each end of the sandwich.

When they ran a current through the electrodes, the sheet expanded and contracted, depending on how much voltage was applied.

RELATED: Device Mimics Human Muscle Size, Strength

This is just the way muscles work; an electrical signal from the nervous system goes to a muscle and causes it to contract or expand. And it's also how speakers make sound. In both cases, current is causing the material to change shape.

In one experiment the scientists attached the other end of the electrodes to a music player and added a current. The rubber sheet vibrated, just like a speaker diaphragm.

If the polymer sheet was squeezed or stretched, either by pinching it or when it vibrated in response to sound, it also generated a small current -- just like some types of condenser or ribbon microphones do.

Suo suggested that the transparent sheet could work as an active noise-cancelling layer on windows. The vibrations from loud noises would make the hydrogel generate an electric current, which could be be used to produce another signal to cancel out the sound.

"We're all, evidently, excited about the possibilities," Rogers said.