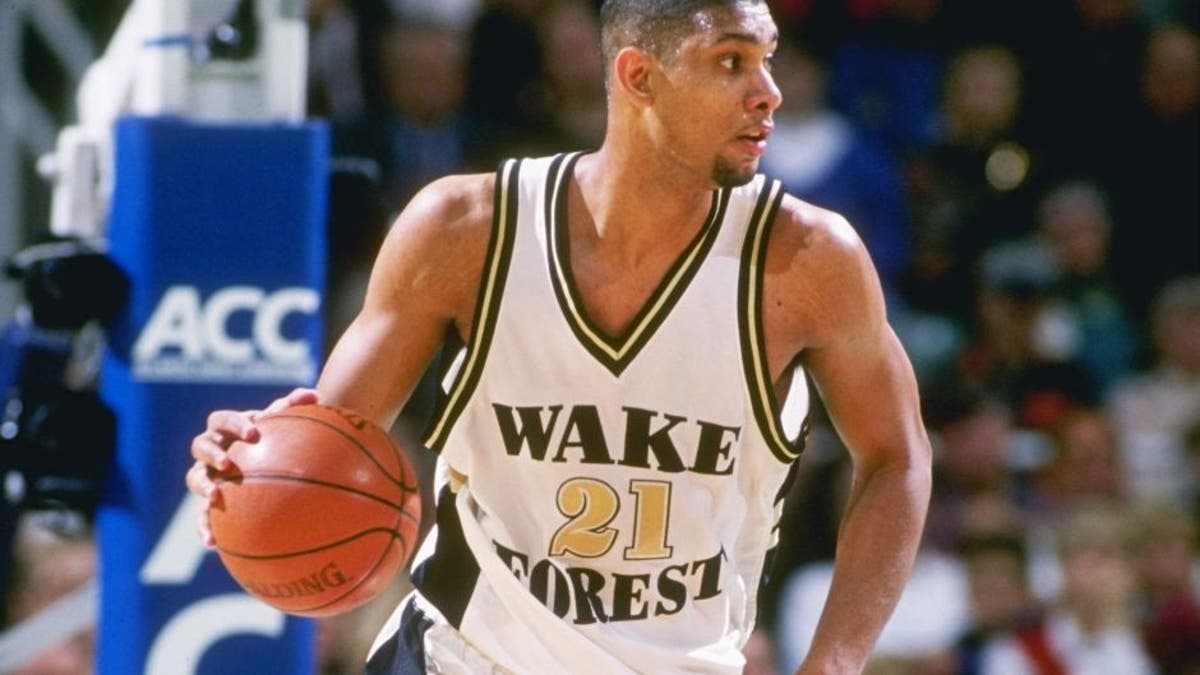

7 Mar 1997: Center Tim Duncan of the Wake Forest Demon Deacons dribbles the court during a playoff game against the Florida State Seminoles at the Greensboro Coliseum in Greensboro, North Carolina. Wake Forest won the game 66-65. Mandatory Credit: Doug

Thursday night may have marked the end of the 19-year career of two-time NBA MVP, three-time NBA Finals MVP, 10-time first-team All-NBA, 15-time All-Star and five-time NBA champion Tim Duncan, whose San Antonio Spurs lost Game 6 of their Western Conference Semifinal against Kevin Durant, Russell Westbrook and the Oklahoma City Thunder. At 40, it seems likely that Duncan will retire, especially following a year in which he posted career lows in almost every statistical category (even though his Spurs still won a whopping 67 games).

If he does, most basketball eulogies will focus on his time in the NBA - how the can't-miss prospect lived up to expectations and became one of the, if not the best power forward in NBA history. But at occasions like this, sometimes it's just as effective to look back at the man before anyone knew his name, before he was considered one of the greatest basketball players in the world and back to a time when he was just a tall kid living in the Virgin Islands. Tim Duncan had no basketball pedigree. He hadn't touched a ball until he was 14. And he wasn't the subject of an intense recruiting battle having in fact flown under the radar of just about every big-time school in the country.

Duncan was a champion swimmer in St. Croix, where his sister had been an Olympian in 1988. But the following year, when Duncan was a tall, lanky 13-year-old with an eye on the Games in 1992 or 1996, Hurricane Hugo ripped through the island, tearing off roofs, uprooting trees and otherwise leaving the island's main pool useless. All the water surrounding St. Croix didn't help, as swimming in the Caribbean proved fruitless for a number of reasons, namely that swimming in the sea is like playing basketball in a wind tunnel.

Around that time Duncan's beloved mother, Ione, died of cancer. Suddenly finding a place to swim didn't seem as meaningful. After Ione's death, Duncan's sister and her husband, a former D-III player, moved back to St. Croix. It was that husband - Duncan's brother-in-law, Ricky Lowery - who first taught Tim basketball. At 14, he was an age at which most NBA prospects had been playing AAU ball for a half-decade. (Duncan's No. 21 honors Lowery, who wore that number in college.)

Two years later, the U.S. junior team came to the island for some games. The team included Wake Forest senior Chris King, who was asked by his college coach, Dave Odom, whether he'd seen any players worth checking out. King told him of an unpolished, skinny kid who'd held his own with Alonzo Mourning. Odom was on a plane as quickly as you can say "Demon Deacons."

Duncan wasn't entirely unknown. Though he'd been mostly overlooked at an Ohio State basketball camp, word trickled to Rick Barnes at Providence and he and his recruiters went after Duncan hard. But when the team couldn't promise a scholarship until the second part of what would have been Duncan's freshman season, Duncan demurred. Though he'd planned to sign with Providence because they'd been the first team to recruit him, the promise he'd made about getting an education was too important and the guarantee that Wake had given him was too much. He was off to Winston-Salem.

But before he got there, the story of how Tim Duncan and Dave Odom met is classic Duncan - showing his quiet, introverted way while also demonstrating a savvy and complete understanding of the world around him. John Feinstein recounts it in his book, A March to Madness.

Odom flew down to the Virgin Islands and went to the outdoor court where it had been said that Duncan would be playing. The coach sat down and looked in vain for his potential recruit when the teenager showed up next to him instead.

"'Stay calm, Coach," Duncan said. Then he explained the politics of street ball on St. Croix. When the word had gotten around that a big-shot American college coach was in town, everyone who had ever picked up a basketball on the island had shown up to play. Duncan was 16, which made him just about the youngest player on the court. 'If I make them let me play the first game, they'll get upset and put me on a bad team," he said. "I'll lost and I won't get on the court for an hour. If I sit out the first game, though, I can pick my own team and once we got out there, we'll be there for a while.'"

That story caps off with the oft-told five-word line Duncan said to Odom just about as he was set to get on the court. "One more thing, coach," the 16-year-old said, "I can play this game."

Later, Odom would make his pitch to Duncan while the youngster stared at the television the entire time, apparently not listening. But when it came time for Duncan to answer the questions, it was clear he'd been soaking it all in the entire time.

Though Duncan was shut out in his college basketball debut against Division II Alaska Anchorage, he soon blossomed into one of the top players in the country. And despite assurances that he would be the No. 1 pick in both the 1994 and 1995 draft as a sophomore and junior, respectively, Duncan stayed in school for various reasons: a promise to a mother, a love of college and a patience that's served him well in the 20 years since. He'll almost certainly go down as the last top player to pass up being a No. 1 pick (even once) to stay in school another year (not to mention twice). For him, it wasn't even a question. He loved school. He loved his friends. He didn't want to be a 20-year-old traveling 60 nights of the year and hanging out with 30-year-old men. He was all about living in the moment. The money could wait. For Duncan, it all paid off in 1997, when he walked with his diploma, a graduate in psychology at the tiny Winston-Salem school.

Nineteen years later, he may have just graduated again, a 40-year-old man with the rest of his life in front of him. Maybe he'll come back, maybe he won't. But whatever he does, Tim Duncan is going to do it his way.