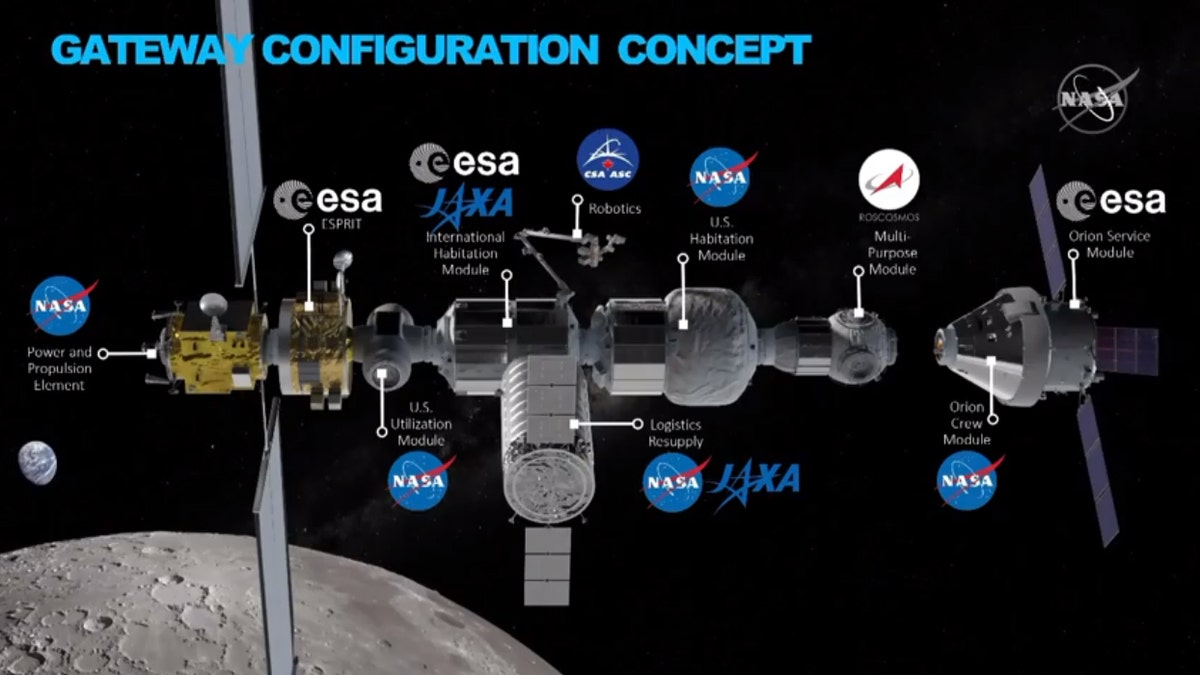

An "aspirational" glimpse at potential partner participation in NASA's Lunar Gateway.

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine praised the agency's 2020 budget proposal from the Trump administration today (March 11), describing how the budget will help the agency reach the moon, and then continue on to Mars.

This path is a common refrain for Bridenstine, who as NASA administrator is tasked with executing the president's Space Policy Directive 1, which called for a renewed focus on human exploration, including a journey to the moon and eventually Mars.

"For the first time in over 10 years, we have money in this budget for a return to the moon with humans," Bridenstine said in a presentation at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. "I'm talking human-rated landers, compatible with Gateway, that can go back and forth to the surface of the moon."

Related: This Is NASA's Plan to Land Astronauts on the Moon in 2028

Bridenstine dedicated a lot of discussion to the Gateway, also called the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway (and formerly the Deep Space Gateway), which is a proposed moon-orbiting outpost that would serve as a waystation to the lunar surface and as a research station. The Gateway is fully funded in the 2020 budget proposal, Bridenstine said.

Pieces of that Lunar Gateway were initially set to launch on an enhanced version of NASA's upcoming Space Launch System rocket, but the budget document suggests a delay in that enhanced SLS development and allows for some components to be launched by commercial rockets. (The SLS would be funded in 2020 for about $375 million less than what the program got in 2019.) The budget proposal includes adding a power and propulsion element by 2022 and other components allowing humans to stay on board starting in 2024, according to a NASA summary presentation.

In Bridenstine's published statement today, he summarizes: "Beginning with a series of small commercial delivery missions to the Moon as early as this year, we will use new landers, robots and eventually humans by 2028 to conduct science across the entire lunar surface." (A new NASA webpage, Moon2Mars, reiterates this timeline.)

The proposal also allots $363 million to purchase commercial flights for cargo to the moon even sooner, a new addition to NASA's budget.

"The president has given us Space Policy Directive 1, which says to go back to the moon, and we're going to do that in short order — maybe even in 2019, but at least by 2020 — with commercial lunar payload services that are going to be funded through the Science Mission Directorate, and all of this is going to be possible because we're looking at going fast," Bridenstine said. He added that they already had science payloads ready for when they find companies to deliver them.

Eventually, once the Gateway was in place, Bridenstine anticipates a broad, international collaboration like the one happening on the International Space Station — two weeks ago, Canada became the first partner to officially join the Gateway project with a proposed Canadarm3 robotic arm.

Bridenstine showed a new "aspirational" visualization of the Gateway, including prospective additions from the Japanese space agency, JAXA, as well as the European Space Agency and the Russian agency, Roscosmos. "This is not what it is right now, today, but this is aspirational," he said — there are no concrete commitments for these partners to contribute to the Gateway. "I can tell you, just this morning I got off the phone with all of our international partners on the ISS and others, and they are very excited about partnering with us on going to the moon." The graphic also includes an inflatable habitation module similar to Bigelow's BEAM module undergoing testing at the space station now.

He added that the Gateway would allow NASA "to utilize the resources of the moon. In other words, the hundreds of millions of tons of water-ice that we've already discovered. Water-ice is air to breathe, it's water to drink, it is in fact propulsion, and it's available in hundreds of millions of tons on the surface of the moon. But it's about more than just those things. The last part of his first space policy directive says to take these capabilities for an eventual mission to Mars."

The budget proposal, indeed, fully funds the Mars 2020 mission and a Mars sample-return mission that could launch as soon as 2026 to collect and return to Earth a sample cached by Mars 2020. Both missions would fall under the $2.6 billion budget request for planetary science.

"The moon is the proving ground; Mars is the horizon goal," Bridenstine said. "And both require an all-of-the-above approach."

Beyond the moon and Mars, Bridenstine highlighted funding for the Earth sciences directorate — studying interactions within the water cycle and focusing on predicting weather and air quality, as well as ecosystem change. (Once again, Bridenstine emphasized that NASA would follow National Academy of Sciences guidelines prioritizing studying climate change.)

He also confirmed that the James Webb Space Telescope, delayed until a 2021 launch, would receive full funding. The budget proposal documents, however, provide no funding to the WFIRST telescope, two Earth science missions and the Office of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Engagement.

This 2020 budget proposal from the administration still must be approved by Congress before going forward; in the recent past, WFIRST, STEM education funding and Earth science missions have all been re-added in Congress' budget bill after being cut from the original proposal.

- Bridenstine Worried About Budget Pressures on NASA

- WFIRST Work Continues Despite Budget and Schedule Uncertainty

- NASA's SLS Megarocket Over Budget, Behind Schedule, Report Finds

Original story on Space.com.