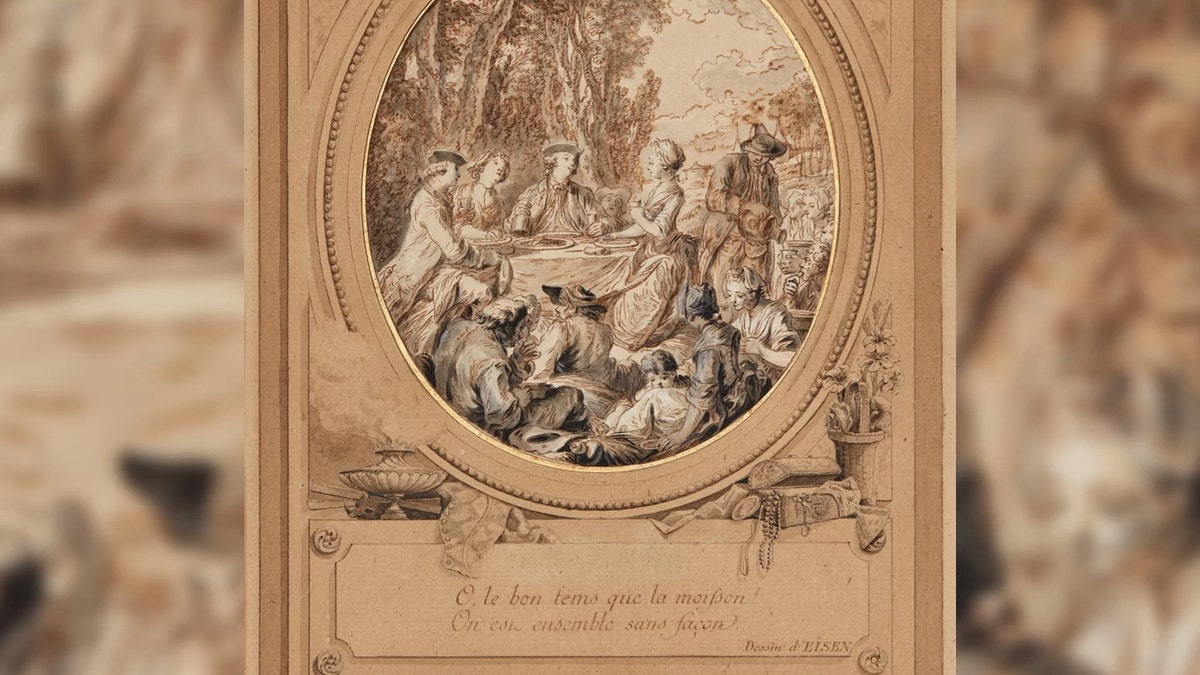

Preparatory sketch with a drawn frame for an illustration of the Comedy Les Moissonneurs, 1768, by Charles Dominique Joseph Eisen (1720–1778). Credit: Charles Dominique Joseph Eisen/Courtesy of the Bundeskunsthalle museum

BERLIN —A crowd gathers joyfully around a dinner table in the 18th-century illustration by the French artist Charles Dominique Joseph Eisen. The scene hides the artwork's dark history: It was robbed nearly 80 years ago from a Jewish family's home in Nazi-occupied Paris.

German investigators announced last week that the artwork and three other drawings have been identified as Nazi loot. They are now on public display here at the Gropius Bau in the exhibition "Gurlitt: Status Report."

The drawings once decorated the home of the wealthy Deutsch de la Meurthefamily, which earned a fortune in the oil industry and sponsored early aviation efforts. After the invasion of France, Nazi officers confiscated the home and used the house as a depot to store works of art and furniture plundered from Jewish homes as part of an operation known as "Möbel Aktion." One of the Deutsch de la Meurthewomen was murdered at Auschwitz. [Images: Missing Nazi Diary Resurfaces]

The rediscovery of the drawings marks a rare recovery of Nazi loot for the Gurlitt task force, a group of German researchers who have been trying to clarify the murky origins of a huge trove of art from a Nazi-era dealer for the past several years.

"There are many stories behind these artworks," said Andrea Baresel-Brand, head of the Department of Lost Art and Documentation for the German Lost Art Foundation. "This is always a very moving thing. When you come to a restitution, there's always a very tragic history forever attached to a work of art."

Gurlitt art trove

In 2012, German authorities entered the Munich apartment of Cornelius Gurlitt, a reclusive elderly man who was under investigation for tax evasion. Inside, they found hundreds of pieces by famous artists, including Picasso, Monet, Renoir and Rodin. The man had inherited the collection from his father, Hildebrand Gurlitt, a dealer who worked with the Nazis to acquire art for planned museums, such as Hitler's never-realized Führermuseum in Linz. Hildebrand Gurlitt was also one of just four dealers approved to sell off art considered "degenerate" because it was modern, "un-German," or made by Jews and communists.

German authorities confiscated the art from Cornelius Gurlitt's Munich apartment and another apartment in Salzburg, Austria, in 2012. When news of the trove became public in 2013, the German government launched a task force to research the provenance, or origins, of the art, to determine if any of the 1,566 pieces were looted or unethically acquired during the Nazi regime.

So far, only six works have been restituted, including a portrait of a woman stolen from Jewish French politician Georges Mandel in Paris, identified last year by a repair in the canvas and on public view again in Berlin. The task force has faced some criticism over the slow pace of the investigation.

"With the Gurlitt art trove, the term 'provenance research' has become familiar to quite a lot of people, and I think that we created new awareness for younger generations about what happened in the Nazi era, how people were robbed and plundered," Baresel-Brand told Live Science. She added that she thinks the public has also become more aware of how vague the provenance of an art object can be even after a thorough investigation. "Even though we have good funding and perfect researchers, even they sometimes can't clarify a provenance to say that this is a work that came from a family or not."

In the span of 80 years, artworks can change frames, documents can be lost or forged, archives can be destroyed and titles of pieces can change, Baresel-Brand explained, and victims of the Holocaust may not have had proof of the objects they lost. [6 Archaeological Forgeries That Could Have Changed History]

New drawings come to light

The four recently discovered drawings were not part of Cornelius Gurlitt's trove.

Provenance researchers found that Cornelius Gurlitt's sister, Benita Gurlitt, had also inherited several works of art from their father. Among these works of art were the Deutsch de la Meurthefamily's drawings. The researchers essentially posted a missing notice for the drawings on Germany's Lost Art database in July 2017. An unnamed owner came forward with the artworks and agreed to return the drawings. The descendants of the Deutsch de la Meurthe family gave their approval for the works of art to be displayed. [30 of the World's Most Valuable Treasures That Are Still Missing]

The records of the Möbel Aktionprogram were destroyed, so there is a gap in the paper trail connecting Gurlitt to the confiscated drawings.

"It remains unclear whether Gurlitt had access to stores of this kind or could obtain 'goods' from them through middlemen," the exhibition catalog says. "What is certain is that the family did not voluntarily leave the four works behind and that they must therefore be considered as Nazi-looted cultural assets."

About 200 other pieces of suspicious art from the inventory are on display at the"Gurlitt: Status Report" exhibition. (The artworks were first featured in November 2017 in a joint exhibition atSwitzerland's Kunstmuseum Bern and Germany's Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn.) Most of the "degenerate" art on display —by artists like Edvard Munch, Emil Nolde, George Grosz and Otto Dix —is not considered Nazi loot because these pieces were predominantly taken from German public institutions.

Baresel-Brand told Live Science that she thinks Hildebrand Gurlitt was "a very intelligent person profiting from a situation" and noted that criticism should also be directed at the shortcomings of postwar society in Germany. "You have many continuities —people coming back to their offices like Hildebrand did."

After the war, Hildebrand Gurlitt was exonerated in his denazification trials, in part because he pointed to Jewish heritage from one of his grandparents, recasting himself as a potential victim of the Nazi regime. His art collection was briefly confiscated by the U.S. Army's "Monuments Men" team, but most works were returned to him after he swore that his business records had been destroyed and that none of the collection came from Jewish families. He went on to become the director of the Kunstverein Museumin Düsseldorf.

"He wanted to survive," Baresel-Brand said. "He wanted his family to have a happy life. This is understandable, but of course it doesn't legitimize his actions."

Original article on Live Science.