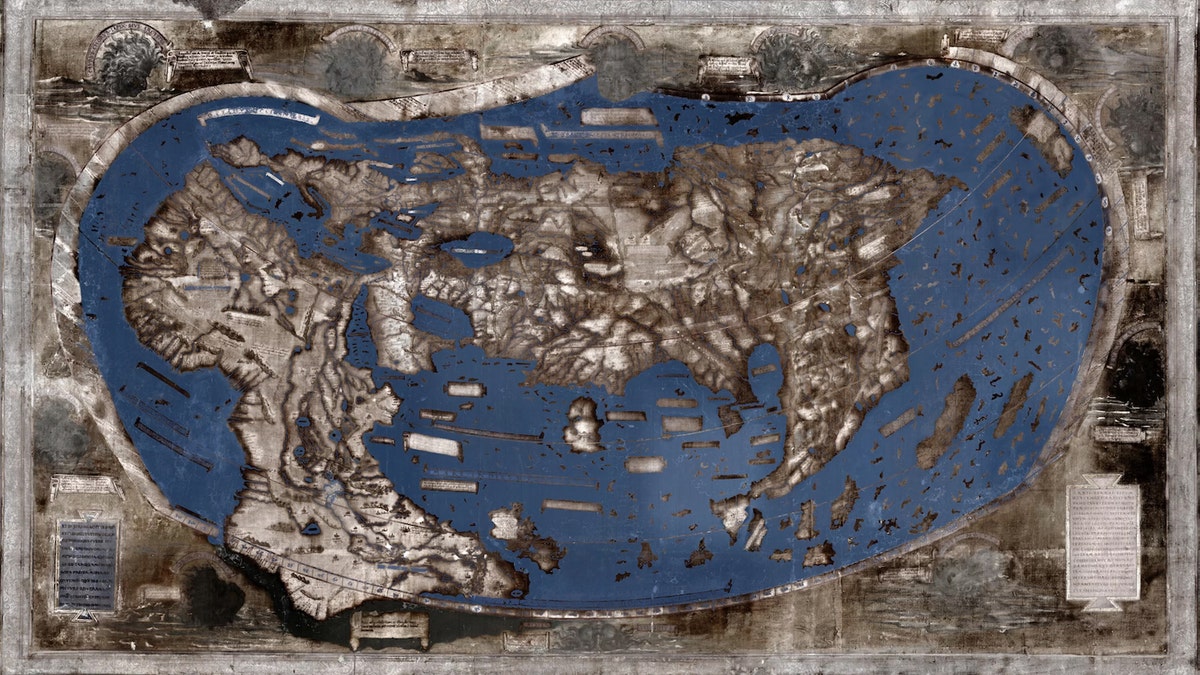

The researchers used multispectral imaging to reveal the images and text on the map. Credit: Image by Lazarus Project / MegaVision / RIT / EMEL, courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

A 1491 map that likely influenced Christopher Columbus's conception of world geography is getting a new lease on life, now that researchers have revealed its faded, hidden details with cutting-edge technology.

Researchers pulled off this feat by turning to multispectral imaging, a powerful digital tool that can recover texts and images on damaged documents, said the project's leader, Chet Van Duzer, a board member of the multispectral imaging group known as The Lazarus Project at the University of Rochester in New York.

"Almost all of the writing on the map had faded to illegibility, making it an almost unstudyable object," Van Duzer told Live Science. But after the high-tech imaging uncovered the map's minutia, he was able to show that this 527-year-old map not only influenced Columbus but was also integral to Martin Waldseemüller's legendary 1507 map, which was the first to call the New World by the name "America." [See Images of the Newly Deciphered 1491 Map]

Long and winding road

The map — created by German cartographer Henricus Martellus in Florence — shows the world as Westerners knew it in 1491, right before Columbus set sail. In his 4-foot by 6.6-foot (1.2 by 2 meters) map, Africa (albeit, a greatly lopsided one) in on the left; above Africa is Europe, with Asia to the east; and Japan sits near the far-right corner.

Of course, the map doesn't show North and South America, which were still unknown to the Western world. (Although, arguably, the Vikings likely settled parts of Canada in about A.D. 1000.)

The map is so old, it has a somewhat murky provenance. It reportedly belonged to a family in Tuscany, Italy, for years before it resurfaced in Bern, Switzerland, in the 1950s. Then, it was sold and anonymously donated to Yale University in 1962, Van Duzer wrote in his new book, "Henricus Martellus's World Map at Yale (c.1491)," which Springer is publishing next week.

The paper map was already extremely faded in the 1960s. So, Yale researchers attempted to decipher its text by taking ultraviolet photos of it. These images revealed previously unknown text on the map, but it didn't reveal all of the map, Van Duzer said.

Revealing technology

Intrigued, Van Duzer secured a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, partnered with The Lazarus Project and spent 10 days photographing Martellus' map at Yale's Beinecke Library.

The team used a number of different wavelengths to photograph the map, from ultraviolet to infrared, "because Martellus was using different pigments to write this text, and they respond differently to light," Van Duzer said.

Roger Easton, a professor at the Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science at the Rochester Institute of Technology, in New York, sifted through the various images, noting which aspects looked best in different wavelengths. Then, he made digital composite images that revealed the illegible elements on Martellus' map.

The entire process took months, Van Duzer said. "[It] was very exciting and very gratifying" when he finally saw the digitally enhanced copy, he said.

Inspiring map

For starters, the map doesn't have sea monsters, as many other maps from the Renaissance do. That's because many cartographers weren't skilled illustrators and would often pay an artist to paint the monsters for them. This, in turn, increased the cost of the map, which commissioners sometimes couldn't afford, Van Duzer said.

Secondly, the abundance of Latin text on the map helped Van Duzer understand what had inspired Martellus, as well as whom he inspired. [Photos: Renaissance World Map Sports Magical Creatures]

Martellus used a number of books to inform his map, including the 1491 book "Hortus Sanitatis," which describes animals around the known world. He also gleaned knowledge from the 1441-43 Council of Florence, where African people talked about the geography of their homeland.

As for being an inspiration, Columbus likely saw this map (or at least another version of it), Van Duzer said. In a biography, Ferdinand Columbus noted that his father thought that Japan ran north-south, like it does on this map. And Martellus' creation was the only map of Japan at the time showing this orientation, Van Duzer said. In essence, this map likely influenced Columbus' ideas about the geography of Asia.

In addition, Martellus' map likely influenced Waldseemüller's 1507 map. Waldseemüller described the New World as "America" based on the misconception that the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci had discovered the New World. Once Waldseemüller realized his error, he tried to change it, but it was too late: The name "America" had caught on, and was here to stay, Van Duzer said.

Original article on Live Science.