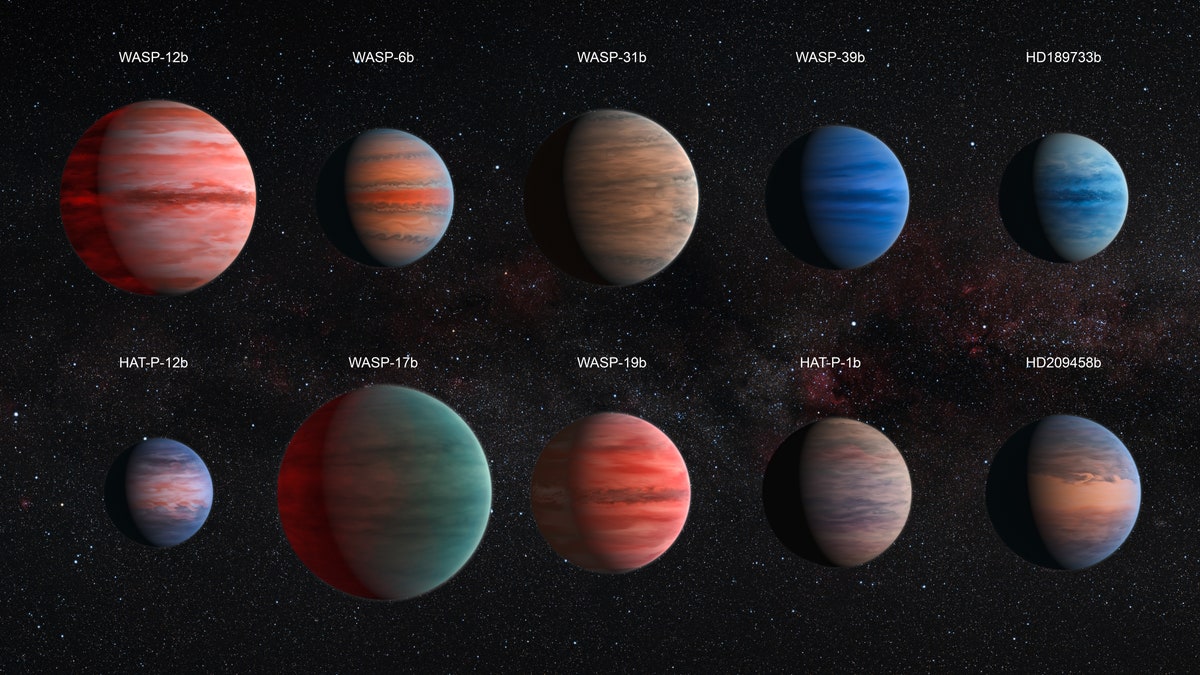

This image shows an artistâs impression of the ten hot Jupiter exoplanets studied by David Sing and his colleagues. The images are to scale with each other. HAT-P-12b, the smallest of them, is approximately the size of Jupiter, while WASP-17b, the largest planet in the sample, is almost twice the size. The planets are also depicted with a variety of different cloud properties. (ESA/Hubble & NASA)

One of the mysteries around several hot, Jupiter-sized exoplanets is why they appeared to harbor so little water.

Now, a team of researchers using NASA's Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes has come up with the answer, which could provide a better understanding of planetary atmospheres and even how planets in our galaxy are assembled.

These planets, it turns out, had water all along.

Related: Scientists discover closest-ever Earth-sized exoplanet

"Our results suggest it's simply clouds hiding the water from prying eyes, and therefore rule out dry hot Jupiters," Jonathan Fortney of the University of California, Santa Cruz and a co-author on a paper published. "The alternative theory to this is that planets form in an environment deprived of water, but this would require us to completely rethink our current theories of how planets are born."

The University of Deleware's John Gizis, who studies brown dwarfs, a kind of "failed star" that evolve similarly to Jupiter-like gas giant planets and did not take part in the study, called the findings "a real breakthrough."

"I am convinced by their case that hazes and clouds are responsible for the diversity of exoplanet spectra," he told FoxNews.com.

"Some astronomers hoped we were seeing direct evidence of a diversity of composition and therefore direct results of planet formation differences, but that model now seems to be ruled out," he said. "Instead, we are learning that clouds aren't always the same. Astronomers now face a major challenge: Is it possible to get past the effects of hazes and clouds to find the underlying clues to planet formation? Perhaps these clues can only be recovered in the planets that happen to have clear atmospheres."

Of the nearly 2,000 planets confirmed to be orbiting other stars, NASA has said that a subset of them are gaseous planets with characteristics similar to those of Jupiter. However, they orbit very close to their stars, making them incredibly hot and hard to study.

From those explored by Hubble so far, several were found to hold less water than predicted by atmospheric models. That seemed odd and prompted an international team of astronomers to embark on what would become largest ever spectroscopic survey of exoplanet atmospheres.

Related: Ancient exoplanets raise prospects of intelligent alien life

"The atmosphere leaves its unique fingerprint on the starlight, which we can study when the light reaches us," co-author Hannah Wakeford, now at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said in a statement.

They were assisted by the Wide Field Camera 3 that was only recently installed on Hubble and has technology that allowed them to attain a much broader spectrum of light - covering wavelengths from optical to infrared – than in the past. For example, the infrared is sensitive to all molecules like water and optical picks up scattering like clouds.

As a result, the team found a correlation between hazy or cloudy atmospheres and faint water detection and also helped them demonstrate the range of atmospheres on these planets.

“Now that we are able to see a lot of planets, 10 planets and see the full broad spectrum, we are able to see planets that have clear atmospheres and a lot of water and those that show little features are the cloudy ones,” David Sing, of the University of Exeter and the lead author of the paper, told Fox News.

“It definitely tells us exoplanets are very diverse and their composition is diverse,” he said. “Since we now know water is common on hot Jupiters – they are not devoid of water – that does lead to the prospect that other smaller planets may have lots of water as well.”

Related: 2 planets may lurk in solar system beyond Pluto, study says

The presence of water on these planets is not an indication of life – since these are such harsh environments. But the study authors suggest the findings could help scientists determine how these planets were formed – a prospect that has been helped by the discovery in recent years of so many exoplanets.

“In the broader sense, we are trying to understand exoplanet atmospheres and how they work essentially,” Sing said. “No two planets look the same … The planets have a lot of character.”

And by gaining insight into these exoplanets, Sing said that would contribute to the goal of finding “signatures of life on other planets” and one day finding an Earth-like planet with an environment like ours.

“The way we are going to do that is to look for gases in the atmosphere and associate those with conditions of life,” he said. “In order to do that, we are going to have to compare many different planets to really understand what is going on.”