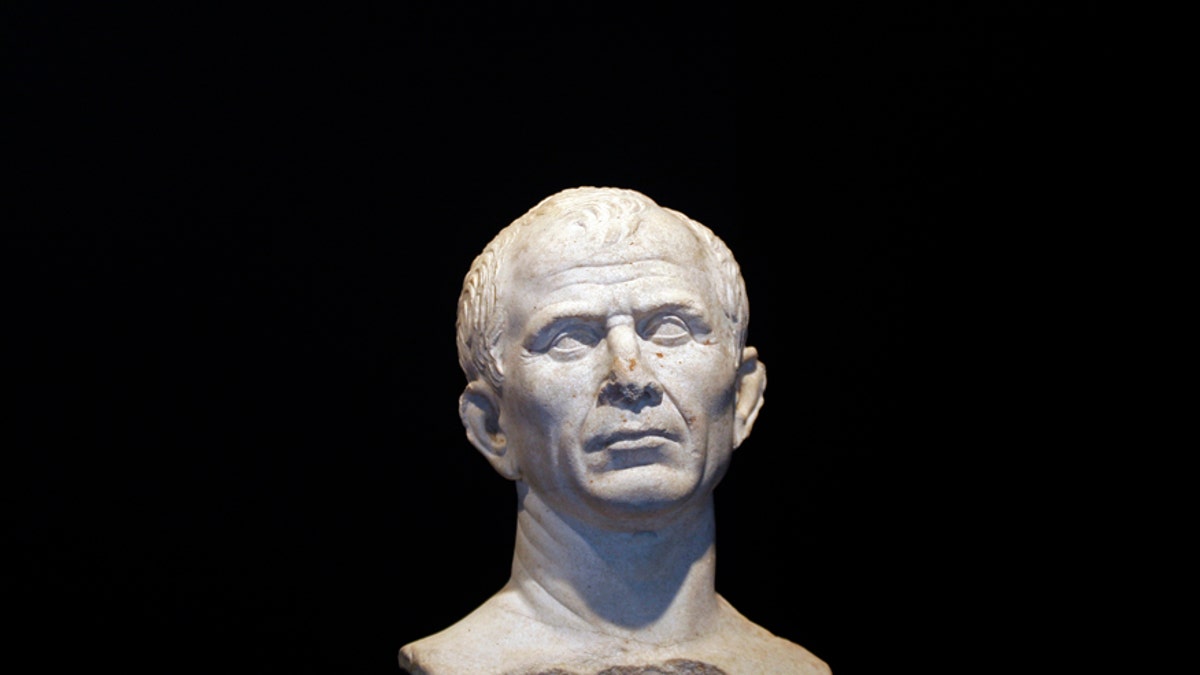

File photo: A life-size bust of Julius Caesar is seen at new buildings of the Department of the underwater and submarine archaeological (DRASSM) in Marseille, January 22, 2009. The bust of Cesar, dated 49-46 BC, was discovered last year as part of underwater archeological exploration in the Rhone River near Arles. (REUTERS/Jean-Paul Pelissier)

Ancient Rome was a dangerous place to be an emperor. During its more than 500-year run, about 20 percent of Rome's 82 emperors were assassinated while in power. So, what led to their downfalls?

According to a new study, we can blame it on the rain.

Here's the reasoning: When rainfall was low, troops in the Roman military — who depended on the rain to water crops grown by local farmers — would have starved. "In turn, that would have pushed them over the edge to potentially mutiny," said study lead researcher Cornelius Christian, an assistant professor of economics at Brock University in Ontario, Canada. [In Photos: Ancient Home and Barracks of Roman Military Officer]

"And that mutiny, in turn, would collapse support for the emperor and make him more prone to assassination," Christian told Live Science.

Christian, who considers himself an economic historian, made the discovery by using ancient climate data from a 2011 study in the journal Science. In that study, researchers analyzed thousands of fossilized tree rings from France and Germany and calculated how much it had rained there (in millimeters) every spring for the past 2,500 years. This area once comprised the Roman frontier, where military troops were stationed.

Then, Christian pulled data on military mutinies and emperor assassinations in ancient Rome. From there, "it was really just a question of piecing together these different pieces of information," Christian said. He plugged the numbers into a formula and found that "lower rainfall means that there's more probability of assassinations that are going to take place, because lower rainfall means there's less food."

Make it rain

Take, for instance, Emperor Vitellius. He was assassinated in A.D. 69, a year of low rainfall on the Roman frontier, where the troops were stationed. "Vitellius was an acclaimed emperor by his troops," Christian said. "Unfortunately, low rainfall hit that year, and he was completely flabbergasted. His troops revolted, and eventually he was assassinated in Rome."

But, as is often the case, many factors can lead to an assassination. For example, Emperor Commodus was assassinated in A.D. 192 because, in part, the military got fed up when he began acting above the law, including making gladiators purposely lose to him in the Colosseum.

There wasn't a drought leading up to Commodus' assassination, "but usually there is a drought preceding the assassination of the emperor," Christian said. "We're not trying to claim that rainfall is the only explanation for all these things. It's just one of many potential forcing variables that can cause this to happen."

The study is part of a burgeoning field that examines how climate affected ancient societies, said Joseph Manning, a professor of classics and history at Yale University who wasn't involved with the new research. Last fall, Manning and his colleagues published a study in the journal Nature on how volcanic activity may have led to the drier conditions that doomed the Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt, Live Science previously reported.

However, while the new study lays a "good groundwork" for the rainfall-assassination hypothesis, the researchers have a long way to go to support this idea, Manning said. For starters, it's relatively simple to find a correlation between two things using statistics, he said. "They do some pretty good statistical work, but how do you know you've got the right mechanism?" [Photos: Gladiators of the Roman Empire]

In other words, correlation does not equal causation, Manning said. But, given the promise of this preliminary research, it's worth the effort to dig into this hypothesis to determine whether climate data actually jibes with assassination dates, from the empire's start in 27 B.C. to its end in A.D. 476, Manning said.

The hypothesis "sounds plausible," said Jonathan Conant, an associate professor of history at Brown University who wasn't involved with the study. But while rain may have played a role, so did other factors, Conant said. For instance, most of Rome's assassinations happened in the third century A.D. At this time, the Roman Empire had massive inflation, disease outbreaks and external wars, all of which took a toll on the empire's stability, Conant said.

"For me, [the rainfall-assassination hypothesis] adds another layer of complexity and nuance to our understanding of the political history of the Roman Empire, especially in the third century," Conant told Live Science.

The study is published in the October issue of the journal Economics Letters.

Original article on Live Science.