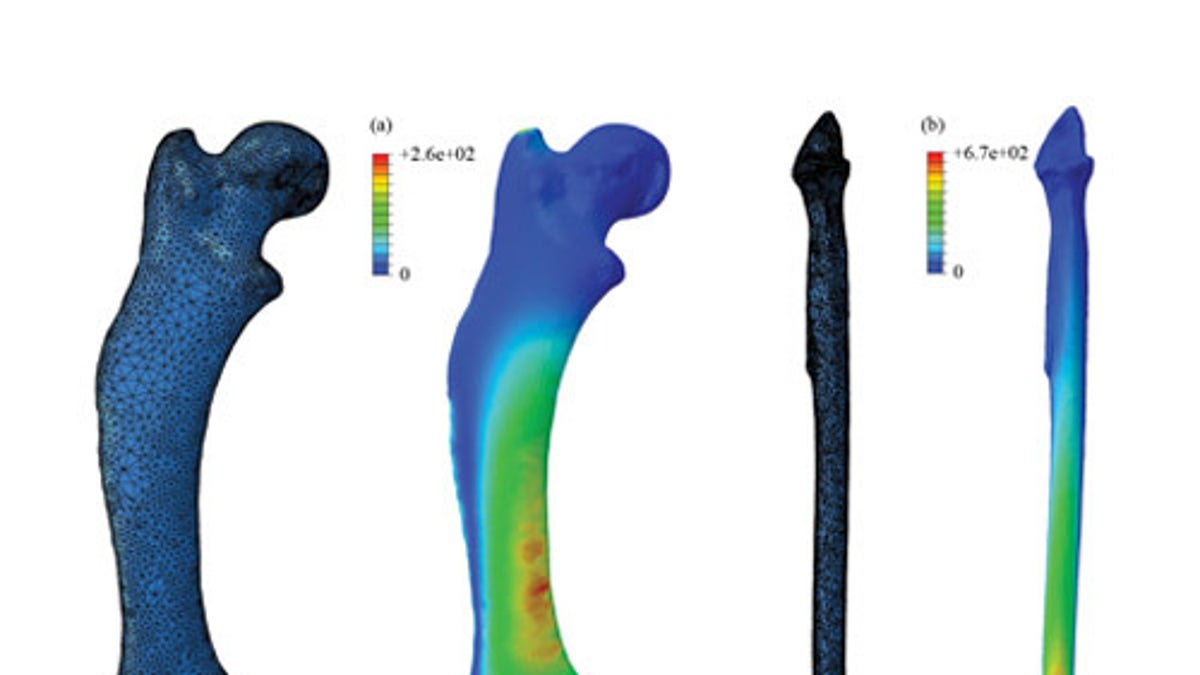

By simplifying leg bones down to basic columns, previous studies could have underestimated the stresses experienced in animal limbs by up to 142 percent. Stress shown here in the common hedgehog's femur (a), and a tibia of a large bird, Uria (b (Charlotte Brassey)

The fact that bones have curves has now thrown a curveball into calculations of dinosaur weight, researchers say.

New estimates suggest dinosaurs may have been lighter than once thought, scientists explain.

With the rare exceptions of fossilized scraps of skin, feathers, bristles and other relatively soft tissues, all that remains of most extinct creatures are their skeletons. One way that investigators seek to learn more about these lost animals is to deduce their weight from their bones.

Traditionally, researchers would calculate estimates of dinosaur mass using a leg measurement such as the circumference of leg bones, understanding the relationship between body mass and this circumference in modern animals, "and scaling this up to the size of a dinosaur," said researcher Charlotte Brassey, a biomechanist at the University of Manchester in England.

For the sake of simplicity, these calculations often model leg bones as columnar beams. However, "as soon as we introduce irregularities into their shape — the lumps, bumps and curves that are typical of animal bones — then they no longer behave like columns," Brassey told LiveScience. [Gallery: Stunning Illustrations of Dinosaurs]

Dinosaur crash tests

To overcome any errors that simplifying these curved organic structures might introduce, the scientists developed complex 3-D models of leg bones from eight modern animal species — the giraffe; the white-tailed eagle; the American flamingo; the European hedgehog; the common murre, a large bird; the rock hyrax, a guinea piglike animal; the Senegal bush baby, a type of monkey; and the European polecat, a weasel-like animal.

When the researchers digitally crash-tested the bones by virtually loading stress on the ends of the bones, they found "the smallest change in the position or direction of loading induced significant amounts of bending," Brassey said.

By simplifying leg bones down to basic columns, previous studies could have underestimated the stresses experienced in animal limbs by up to 142 percent.

"We've always known that reducing bones down to simple beams was a huge simplification," Brassey said, but it was only after she created the models and compressed them "that I realized how infeasible it was."

True dinosaur mass

This raises concerns that past equations regarding fossil species, including dinosaurs, could have overestimated the maximum body weight their legs were capable of supporting.

"Unfortunately, it's not as simple as saying, 'These equations underestimate stress by 20 percent.' Instead, it depends on the underlying shape of the bone," Brassey said. "A whole-body approach to mass prediction in dinosaurs might be preferable."

When the researchers carried out such a whole-body approach to mass prediction with Giraffatitan, the giant dinosaur previously called Brachiosaurus, they came up with a body mass of 25 tons (23 metric tons), "which is quite a bit lower than some previous predictions," Brassey said. Previous mass estimates for Giraffatitan ranged from 31 to 86 tons (28 to 78 metric tons.)

"Other scientists will argue that finite element analysis remains too computationally expensive and time-consuming," Brassey said. "We appreciate this, and have also introduced improvements to the beam equations in our study for those who do not wish to use finite element analysis." (Finite element analysis is a method of breaking down a problem into many small elements that can be solved in relation to one another using complex equations.)

The findings another intriguing question: Why are bones curved in the first place?

"We've found that it massively increases stress levels when loading the bones in compression, which would be disadvantageous, yet most bones still have some degree of curvature, so evolution hasn't acted to get rid of this curvature," Brassey said.

There have been plenty of suggestions as to why the curvature is there — for instance, to pack muscles around the bones. "But we still haven't really come up with the solution yet," Brassey said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Nov. 21 in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

Copyright 2012 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.