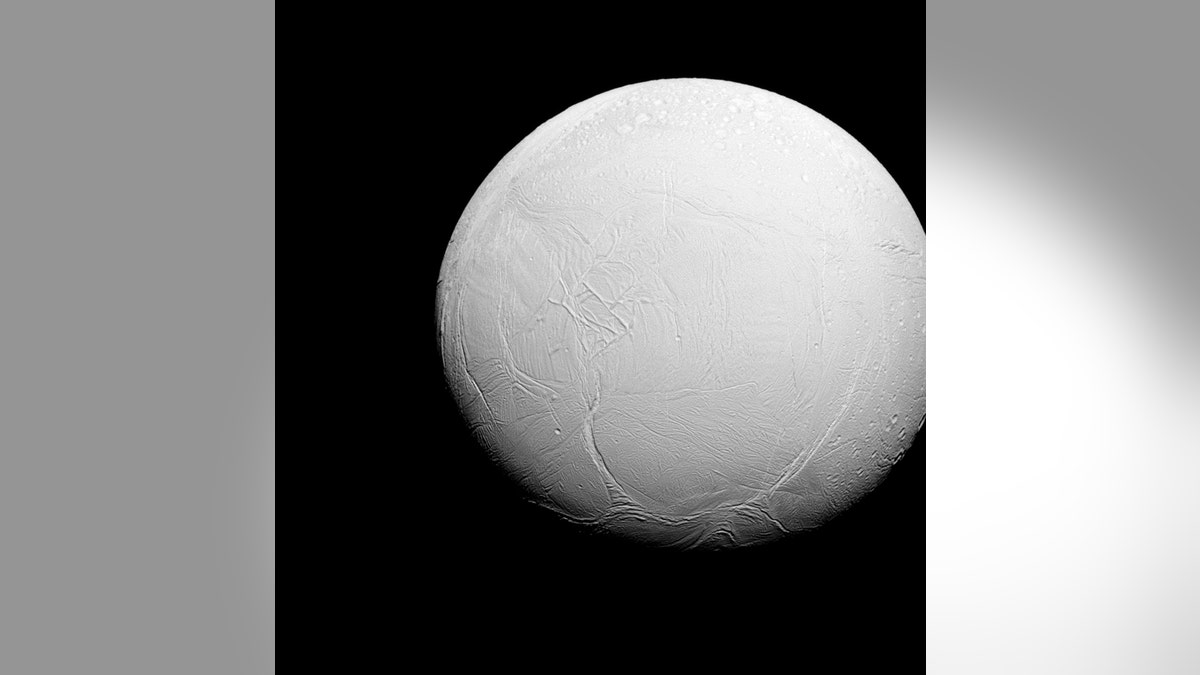

Enceladus, the sixth-largest moon of Saturn, is shown in this photo taken in visible green light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on July 27, 2015 and released on October 27, 2015. (REUTERS/NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute/Handout)

A small water jet on Enceladus, an icy moon of Saturn, spews its fiercest eruptions when the moon is farthest from the planet, a new study suggests, but the overall gas output doesn't increase much during that time. The study points to a mystery in Enceladus' plumbing.

The surprise observation came after looking at the moon using the Saturn-orbiting Cassini spacecraft in March. Enceladus is considered a prime potential location for life because under its icy surface is a global, salty water-ocean that could have the right ingredients for microbes.

Cassini has seen Enceladus erupt many times since arriving in 2004. More than 90 percent of the material in the observed plumes contains water vapor, which researchers said they believe is vented from Enceladus' subsurface ocean. [See Cassini's Amazing Photos of Enceladus]

Previous Cassini observations showed there is three times as much dust sprayed into space when Enceladus is furthest away from Saturn than when it's close by. The new work focused on how much gas erupted along with that dust, propelling it outward. Cassini observed the plume from Enceladus as it blasted in front of Epsilon Orionis, the central star in Orion's belt, and measured the light that passed through that plume using the ultraviolet imaging spectrometer, UVIS. The researchers expected quite a lot more gas expelled at the far part of Enceladus's orbit, to help explain the outpouring of dust, but they found the gas output had bumped up by just 20 percent, far less than expected.

"We went after the most obvious explanation first, but the data told us we needed to look deeper," Cassini UVIS scientist Candy Hansen said in a statement. Hansen, who is based at the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona, led the study's observational planning.

Hansen's team zeroed in on an individual jet nicknamed "Baghdad I." The researchers discovered that this particular jet was four times more active when Enceladus is furthest from Saturn, compared with other times in the moon's orbit.

When Enceladus is furthest from Saturn, Baghdad I's water output alone makes up 8 percent of the observed water plume, which consists of several jets located along "tiger stripes" or cracks in the ice of the moon. At other points in the orbit, Baghdad I's water represents only 2 percent.

"We had thought the amount of water vapor in the overall plume, across the whole south polar area, was being strongly affected by tidal forces from Saturn. Instead, we find that the small-scale jets are what's changing," said Larry Esposito, UVIS team lead at the University of Colorado, in the same statement.

Esposito added, however, that exactly what is happening beneath the surface still puzzles the team. He said he hopes a future set of scientists can model Enceladus' plumbing to come up with some explanations.

Original article on Space.com.