(REUTERS/SOHO/NASA/Handout)

In November 2016, astronomers watched a young star some 1,500 light-years away from Earth belch out an explosion of plasma and radiation that was roughly 10 billion times more powerful than any flare ever seen leaving Earth's sun. This sudden stellar eruption may be the most luminous known flare ever released by a young star — and it could help scientists better understand the still-murky process of star formation.

"Observing flares around the youngest stars is new territory and it is giving us key insights into the physical conditions of these systems," Steve Mairs, an astronomer and lead author of the study, said in a statement. [Aurora Photos: See Breathtaking Views of the Northern Lights]

Mairs and his colleagues detected the flare using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope, perched atop Hawaii's dormant Mauna Kea volcano. The flare originated from a binary star system — a solar system where two big stars orbit around one another — located in the Orion Nebula, some 1,500 light-years away, researchers reported in the new study, which was published Jan. 23 in The Astrophysical Journal.

This nebula is the closest active star-forming region to Earth and is frequently studied by astronomers interested in the births of stars and planets. (You can actually see the nebula with the naked eye when you look for the Orion constellation; it's the middle "star" in Orion's sword, just south of his belt.)

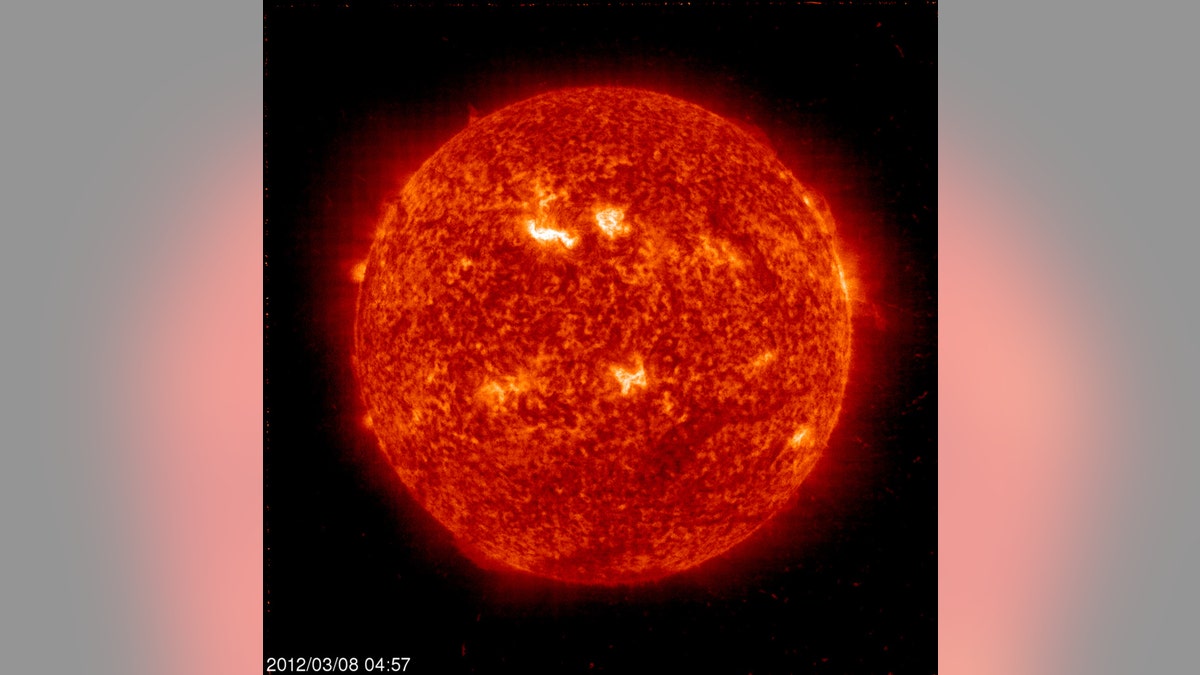

Solar flares occur when a star's magnetic-field lines twist and tangle about each other until they snap, unleashing huge amounts of energy and charged particles. According to NASA, a typical solar flare from Earth's sun releases the energy equivalent of "millions of 100-megaton hydrogen bombs exploding at the same time." When this energy washes over Earth, it can temporarily knock out satellites and short-circuit technology around the world; one famous flare from 1859, known as the Carrington event, caused telegraph wires to shoot out sparks that caused offices to burst into flames.

So, how did the 2016 flare manage to burst billions of times stronger than our sun's worst solar storms? The researchers aren't sure, but it probably has something to do with the fact that the star in question is still very young and sucking up gargantuan amounts of nearby matter to fuel its growth.

Equally unknown are the effects that such massive energy expulsions have on young solar systems. The superhot, X-ray radiation emitted from flares like these could potentially change the chemistry of nearby bodies (like meteors) or possibly alter the atmospheres of young planets, the authors wrote.

Editor's Note: This story was updated to correct the date of the Carrington Event. It occurred in 1859, not 1895.

Originally published on Live Science.