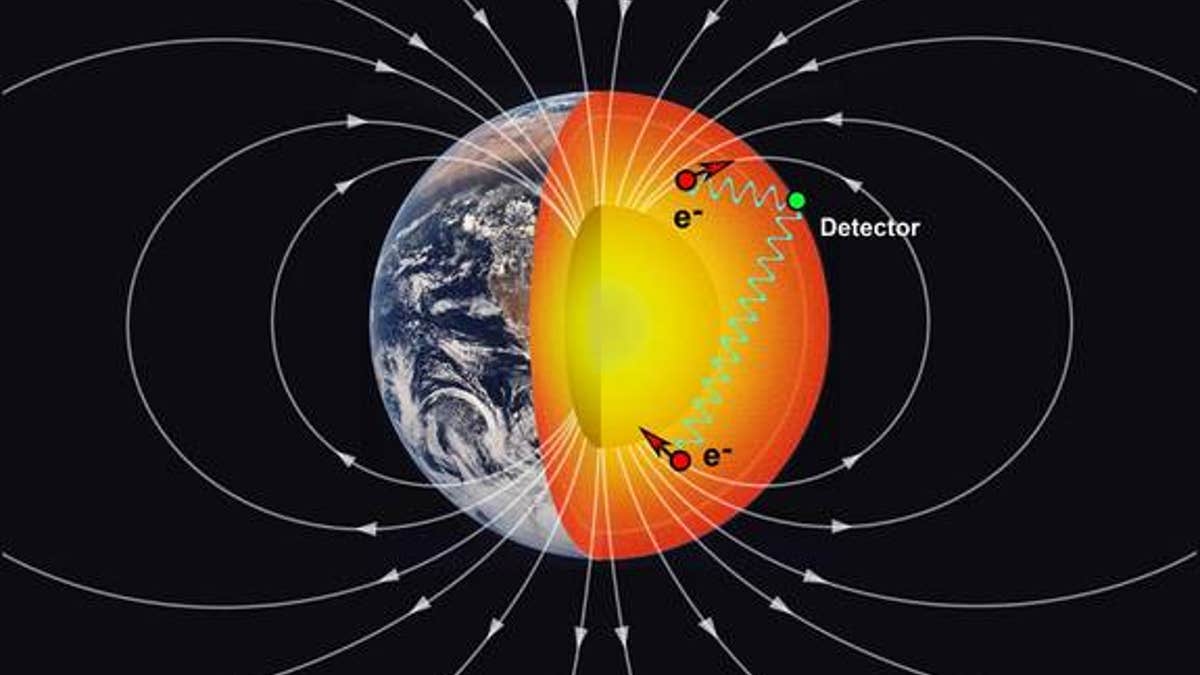

Researchers used an experiment that relied on the electrons (red dots) in Earth's mantle to look for new particles, possibly the unparticle, that are tied to a new fundamental force of nature called the long-range spin-spin interaction (blue wa (Marc Airhart (University of Texas at Austin) and Steve Jacobsen (Northwestern University).)

It's a good time to be a particle physicist. The long-sought Higgs boson particle seems finally to have been found at an accelerator in Geneva, and scientists are now hot on the trail of another tiny piece of the universe, this one tied to a new fundamental force of nature.

An experiment using the Earth itself as a source of electrons has narrowed down the search for a new force-bearing particle, placing tighter limits on how big the force it carries can be.

As an added bonus, if the new particle is real, it will shed light on processes and structures inside Earth, say study researchers from Amherst College and the University of Texas at Austin. The experimental results appear in the Feb. 22 issue of the journal Science.

[pullquote]

The new force of nature carries what is called long-range spin-spin interaction, said lead study author Larry Hunter, a physicist at Amherst. Short-range spin-spin interactions happen all the time: Magnets stick to the fridge because the electrons in the magnet and those in the fridge's steel exterior are all spinning around in the same direction. But longer-range spin-spin interactions are more mysterious. [Wacky Physics: The Coolest Little Particles in Nature]

The force would operate in addition to the four fundamental forces familiar to physicists: gravity, electromagnetism, and the strong and weak nuclear forces. Some physicists think this new force exists because extending the Standard Model of particle physics — a theory that defines the physics of the tiniest particles — actually predicts as-yet undiscovered particles that would carry it.

The unparticle

There are three possibilities for where this force comes from. The first is a particle called the unparticle, which behaves like photons (light particles) in some ways, and like particles of matter in others. The second is one called the Z' (pronounced "Z-prime"), a lighter cousin of the Z boson that carries the weak nuclear force. Both unparticles and Z's arise from extensions of current physical theories. And the third possibility is that there is no new particle at all, but the theory of relativity has some component that is affecting spin.

The unparticle was first proposed in 2007 by Harvard physicist Howard Georgi. Particles have a definite mass, unless they are photons, which are massless. An electron or proton's mass can't change no matter how much momentum it has — change the mass (and thus its energy) and you change the kind of particle it is. Unparticles would have a variable mass-energy.

Though scientists have not yet found a new particle tied to the force, they did see that the long-range spin-spin interaction had to be smaller by a factor of 1 million than earlier experiments showed. If the force exists, it is so tiny that the gravitational force between two particles such as an electron and a neutron is a million times stronger.

The normal, fridge magnet type of spin interactions, mediated by photons, operate only at very short distances. For example, magnetic forces drop as the inverse cube of distance — go twice as far away and the strength of the force drops by a factor of eight. Long range spin-spin forces don't seem to decrease by anywhere near as much. Physicists have been looking for the particles that carry this kind of interaction for years, but haven't seen them. The Amherst experiment puts tighter limits on how strong the force is, which gives physicists a better idea of where to look.

Earth's electrons

Theorists had already known the force they were seeking would be weak and could only be detected over very long distances. So the scientists needed a creative way to look for it. They needed to find a place where tons of electrons were crowded together to produce a stronger signal.

"Electrons have a big magnetic moment," Hunter said. "They align better with the Earth's magnetic field, so they are the obvious choice." Anything that nudges the spins of electrons that line up with the Earth's magnetic field will change the energy of those spins by a small amount. [50 Amazing Facts About Planet Earth]

So the Amherst and University of Texas team decided to use the electrons that are in the mantle of the Earth, because there are a lot of them — some 10^49. "People before prepared samples of spin-polarized neutrons and such," Hunter said. "Their source was close, and controllable. But I realized that with a bigger source you could get better sensitivity."

The reason is that even though only one in about 10 million mantle electrons will align their spin to the Earth's magnetic field, that leaves 10^42 of them. Even though it's not possible to control them the way one would in a lab, there are plenty to work with.

Electron map

The scientists first mapped out the spin directions and densities of electrons inside the Earth. The map was based on the work of Jung-Fu Lin, associate professor of geoscience at the University of Texas and a co-author of the new paper.

To make the map they used the known strength and direction of the Earth's magnetic field everywhere within the planet's mantle and crust. They used the map to calculate how much influence these electrons in the Earth would have had on spin-sensitive experiments that were done in Seattle and Amherst.

The Amherst team then applied a magnetic field to a group of subatomic particles — neutrons in this case — and looked closely at their spins. The Seattle group looked at electrons.

The change in the energy of the spins in these experiments depended on the direction they were pointing. Spins rotate around the applied magnetic fields with a distinct frequency. If the electrons in the mantle are transmitting some force that affects them, it should show up as a change in that frequency of the particles in the lab.

Besides narrowing the search for new forces, the experiment also pointed to another way to study Earth's interior. Right now, models of Earth's interior sometimes give inconsistent answers as to why, for example, seismic waves propagate through the mantle the way they do. The fifth force would be a way to "read" the subatomic particles there — and might help scientists understand the discrepancy. It would also help geoscientists see what type of iron is down there and the actual structure it has. "It would give us information that we mostly don't have access to," Lin said.

Copyright 2013 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.