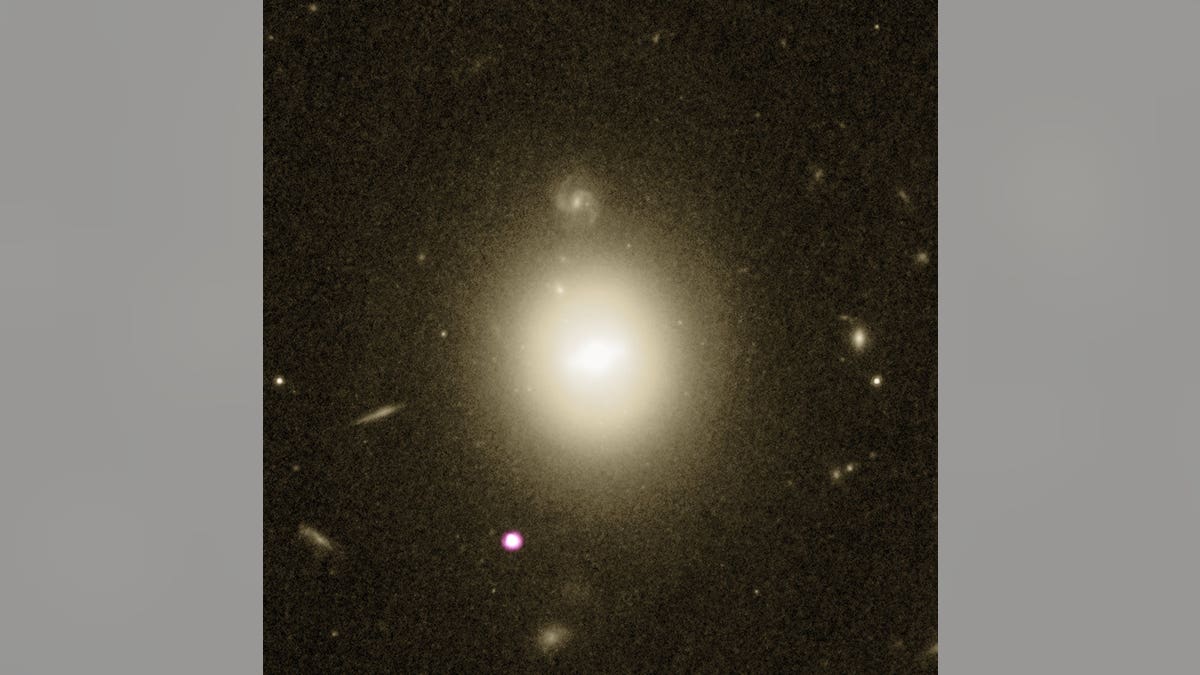

The black hole candidate and its host galaxy (Optical: NASA/ESA/Hubble/STScI; X-ray: NASA/CXC/UNH/D. Lin et al.)

An elusive type of black hole has been spotted as it shreds and consumes a nearby star. Archival data from the European Space Agency's XMM-Newton X-ray space observatory showed signs of the feasting black hole throwing off powerful radiation flares.

Black holes come in many sizes. The smallest, stellar-mass black holes have about as much mass as the sun and are strewn through galaxies, while supermassive black holes can be billions of times larger. These black holes hover at the hearts of most galaxies. The new object is an intermediate-mass black hole, a class ranging from hundreds to thousands of times more massive than Earth's sun. Thought to eventually grow into supermassive black holes, the midsize objects are incredibly difficult to identify, the scientists said.

"This is incredibly exciting: This type of black hole hasn't been spotted so clearly before," lead scientist Dacheng Lin, of the University of New Hampshire, said in a statement. "A few candidates have been found, but on the whole, they're extremely rare and very sought after." [The Strangest Black Holes in the Universe]

Lin and his colleagues pored over archival images collected by XMM-Newton to find the candidate, an X-ray source with the unwieldy name of 3XMM J215022.4-055108. The object sits in a large galaxy located approximately 740 million light-years away from Earth. The researchers confirmed their observations with additional data taken by NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and Swift X-Ray Telescope.

More From Space.com

"This is the best intermediate-mass black hole candidate observed so far," Lin said.

A dying star lights the way

When massive stars lie too close together inside dense star clusters, they can merge to create an intermediate-mass black hole. But by the time the black hole has formed, most of the surrounding gas has been turned into stars, leaving the hungry object with nothing to feast on. So, while stellar clusters are some of the best places to hunt for midsize black holes, these environments can also make the black holes hard to spot.

"One of the few methods we can use to try to find an intermediate-mass black hole is to wait for a star to pass close to it and become disrupted," Lin said. "This essentially 'activates' the black hole's appetite again and prompts it to emit a flare that we can observe."

The passing star is torn to pieces by the gravitational pull of the black hole. As the black hole consumes the star, it creates brilliant flares in X-ray wavelengths. Previously, these events had been spotted only at the centers of galaxies, but the new observation occurs along the galactic edge, the researchers said in the statement.

In addition to observing the radiation in X-ray wavelengths, the researchers used a slew of other instruments to see if they could spot the outburst in visual wavelengths. Two images revealed a change in the source in 2005, as it grew bluer and brighter.

"By comparing all the data, we determined that the unfortunate star was likely disrupted in October 2003 in our time [when the light arrived at Earth] and produced a burst of energy that decayed over the following 10 years or so," co-author Jay Strader, an astronomer at Michigan State University, said in the same statement.

Lin and his colleagues estimated that the black hole has a mass roughly 50,000 times greater than the sun's. Their results were published June 18 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Because stellar-triggered outbursts are thought to be rare for intermediate-mass black holes, the observation of this one suggests the presence of other dormant, midsize black holes at the edges of galaxies in the local universe, the scientists said.

"Learning more about these objects and associated phenomena is key to our understanding of black holes," Norbert Schartel, ESA project scientist for XMM-Newton, said in the statement.

"Our models are currently akin to a scenario in which an alien civilization observes Earth and spots grandparents dropping their grandchildren at preschool: They [the aliens] might assume that there's something intermediate to fit their model of a human life span, but without observing that link, there's no way to know for sure," Schartel said. "This finding is incredibly important and shows that the discovery method employed here is a good one to use."

Originally published on Space.com.