Using land-based GPS measurements on an outlying Tongan island and wave measurements from Pacific sensors, scientists have deduced that the tsunami that devastated Samoan and Northern Tongan islands in 2009 was caused by two earthquakes, not one. (Mick Finn, GNS Science)

LOS ANGELES -- The deadly tsunami that pounded several South Pacific islands last year was spawned by not one but two monstrous earthquakes, surprising new research reveals.

Initially, it was thought that a single powerful magnitude-8.1 jolt triggered the Sept. 29 tsunami that killed nearly 200 people in Samoa, American Samoa and Tonga.

Two teams using different research techniques have now separately concluded that the disaster was the result of a rare double whammy -- two so-called great earthquakes with magnitudes greater than 8 -- that hit within minutes of each other.

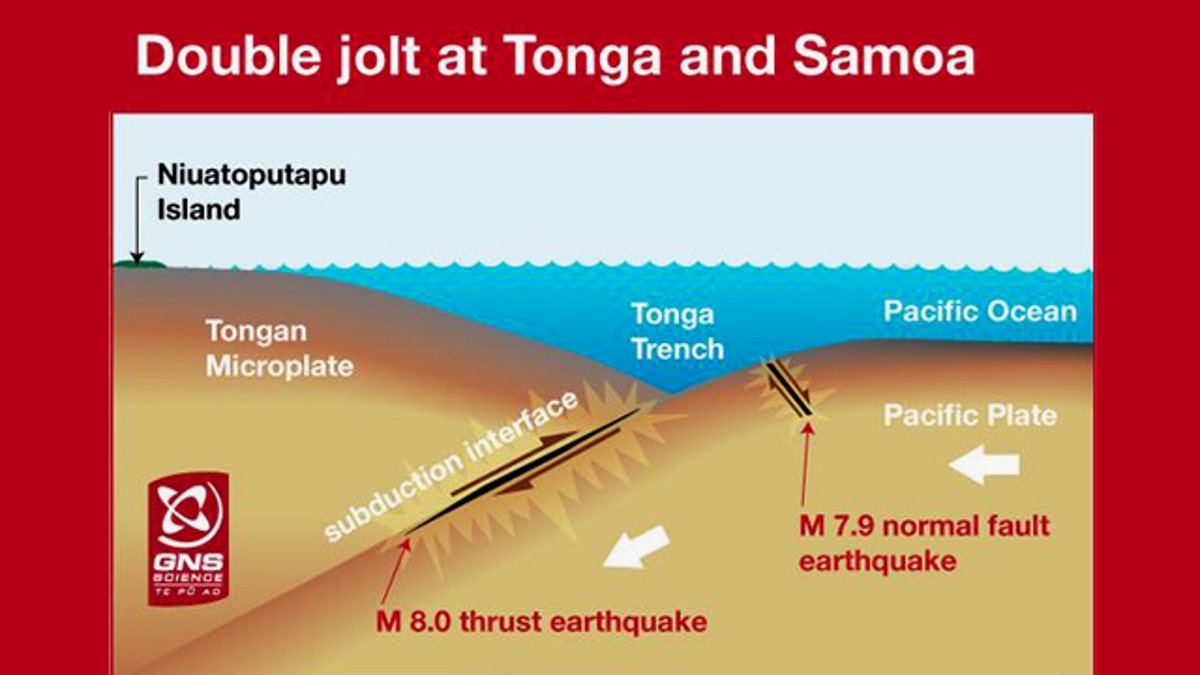

What's notable, they say, was that the quakes occurred along separate fault lines and ruptured differently.

Although the researchers differed on which struck first, their discovery of a one-two seismic punch solves a mystery that has baffled scientists since the disaster.

The findings are published in Thursday's issue of the journal Nature.

When the South Pacific sea floor rumbled last year, scientists initially blamed it on a "outer rise" earthquake of magnitude-8.1 caused by the flexing and bending of the Pacific tectonic plate. But tsunami waves did not arrive at the predicted times and the aftershocks did not cluster around the main quake -- as they normally would -- suggesting that something more complicated was at play.

Using GPS data and deep-ocean tsunami wave observations, a group led by geophysicist John Beavan of the New Zealand geological agency GNS Science determined that the tsunami was actually generated by two powerful quakes -- the magnitude-8.1 "outer rise" quake and a magnitude-8 "megathrust" jolt caused by the diving of one plate under another.

While Beavan's group is not sure which hit first, a separate team led by Thorne Lay of the University of California, Santa Cruz, concluded the magnitude-8.1 quake unleashed the megathrust jolt. Normally, megathrust quakes trigger other jolts. Ground vibrations from the first were so strong that they masked the energy released by the second quake.

The second tremor "does show up clearly on seismic records, but only once you look very hard," Lay said.

Scientists not involved in the latest research said the findings shed light on what happened in the South Pacific, but more work is needed.

"It is difficult to say how typical this behavior is in the region," said U.S. Geological Survey geophysicist Paul Earle. That's because there's a long time between earthquakes and modern instruments weren't available for previous massive earthquakes, he said.