Prof. Harry Jol & Nicole Awad conducting a Ground Penetrating Radar survey at the site of the Great Synagogue of Vilna in Lithuania. (Photographic Credit: Jon Seligman, Courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority)

Experts have used ground penetrating radar to locate the remains of the Great Synagogue of Vilna (Vilnius) in Lithuania, more than 70 years after its destruction by the Nazis.

The radar survey was conducted in the Lithuanian capital in June, uncovering the underground remains of the Great Synagogue and its ‘Shulof’ complex. The Great Synagogue was surrounded by a host of buildings, including other synagogues, a community council, kosher meat stalls, miqva’ot (ritual baths), and the famous Strashun rabbinical library.

The site was also home to Rabbi Eliyahu, the celebrated 18th-century Vilna Gaon, or “genius.”

Constructed in the 17th century, the impressive Renaissance-Baroque-style Great Synagogue was destroyed by the Nazis in 1941. The Soviets built a school on top of the area in 1964.

Related: Archaeologists find rare writing, and then it vanishes

A team led by Israel Antiquities Authority Archaeologist Jon Seligman and Zenonas Baubonis of the Culture Heritage Conservation Authority of Lithuania, together with Richard Freund, the Maurice Greenberg professor of jewish history at the University of Hartford deployed radar technology to locate the Great Synagogue.

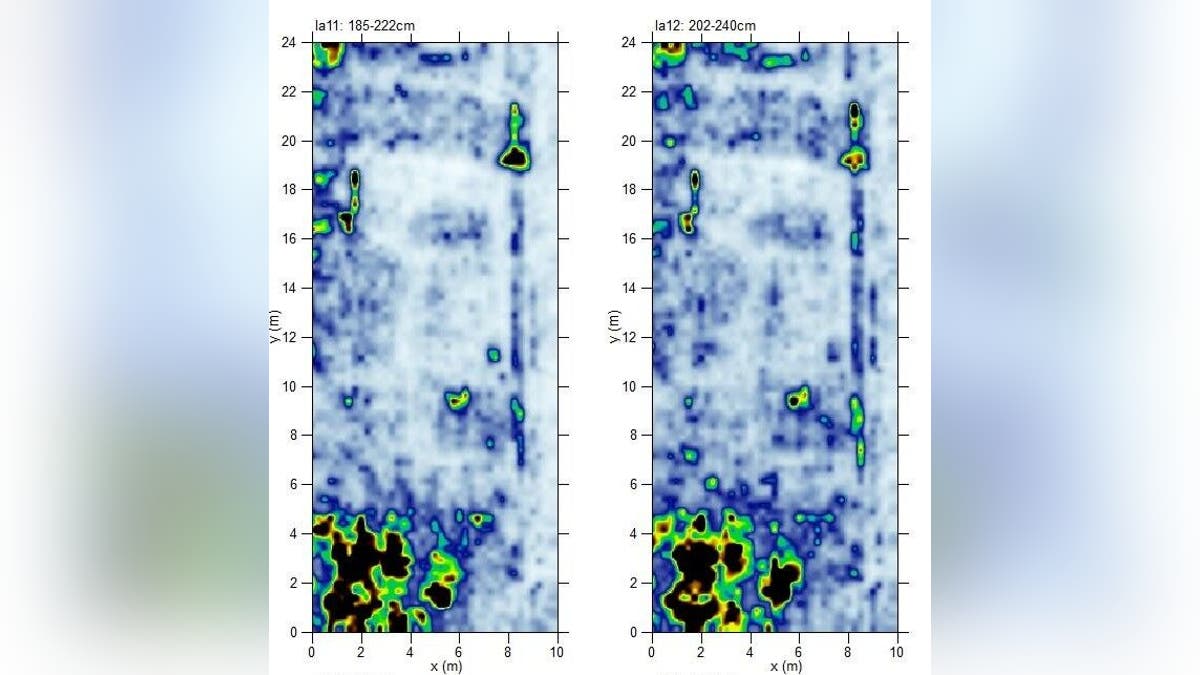

“Ground Penetrating Radar is a tool that allows archaeologists and geoscientists to work together to map an area that they think might yield important finds and explore the sub-surface without disturbing the site,” explained Seligman, in an email to FoxNews.com. “Based on data that is collected, GPS locations can be pinpointed on the site maps so that future excavations can be extremely precise and planned with great care; especially in areas where there are identified artifacts of singular importance.”

The radar system works by sending high frequency electromagnetic waves (similar to FM radio signals) into the ground’s subsurface through antenna. These waves reflect off changes in the materials and layers below the surface and are “collected” by a second antenna.

The Ground Penetrating Radar scan shows an anomaly there is most probably the Miqve (ritual bath) of the Great Synagogue of Vilna. (Israel Antiquities Authority)

The University of Hartford’s Freund told FoxNews.com that much of the Synagogue’s infrastructure was built below ground. According to the rules of the time, the synagogue could not be taller than a church. “In order to build the Great Synagogue in the 17th and 18th centuries they dug down two floors below the level of the street to give the worshippers in the synagogue the experience of a vaulted five story building even though the building appeared from the outside as only a three story building,” he said, in an email.

Freund explained that the Soviets constructed the school above the debris created by the collapse of the Great Synagogue’s upper three floors, with the main floor still lying well below the surface. “That was the reason we used GPR!” he said. “We found excavatable areas around the school where the floor of the synagogue and ritual baths still lie 70+ years later.”

Experts from the University of Wisconsin, Eau Claire, Duquesne University, and the Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem also participated in the project.

Harry Jol, professor of geography and anthropology at the University of Wisconsin, Eau Claire told FoxNews.com that the location posed a unique set of archaeological challenges. “When we arrived on site there is a school and its grounds over the proposed site for research,” he said, in an email, noting that the team worked around the school building, trees, and driveways. “Being in an urban environment also presents its challenges with subsurface electrical, sewer, gas lines and other buried items,” he added.

Related: Ancient burned Hebrew scroll reveals its secrets

With the radar survey complete, excavations are planned at the site in 2016, with the goal of exposing the Great Synagogue’s remains for research.

Seligman told FoxNews.com that, despite the success of the radar survey, the project still faces plenty of challenges. “Resources are needed to conduct the work in Vilnius,” he said. “The other challenges are the usual things we face when working in an urban environment at a site which is defined for other uses - in this case the work will be conducted in a school yard, so we will need to be sensitive to the needs of the school and to make sure that the life of the school is not disturbed.”

The archaeologist also emphasized the excavation’s broad cultural impact. “The historical relationship, especially since the Holocaust, between Lithuanians and Lithuanian Jews has been complex and it is an important part of this project to make sure that the preservation of the Great Synagogue is seen as not only a Jewish interest, but also part of the cultural heritage of Vilnius and Lithuania,” he said.

Follow James Rogers on Twitter @jamesjrogers