Vikings left Greenland because they over-hunted walruses

New research found out why the Vikings left Greenland

A group of international scientists have recovered the oldest known DNA and used it to reveal what life was like 2 million years ago in northern Greenland.

In research published Wednesday in the journal Nature, the group said that biological communities inhabiting the Arctic during the late Pliocene and early Pleistocene epochs remain poorly known because fossils are rare.

With animal fossils hard to find, the researchers extracted environmental DNA from soil samples, including the genetic material that organisms shed into their surroundings.

Researchers were able to get genetic information out of the small, damaged bits of DNA using the latest technology – comparing the DNA to that of different species.

ENDANGERED SEABIRD AT HAWAII VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK CAUGHT ON CAMERA FOR FIRST TIME

The samples came from a sediment deposit called the Kap København formation in Peary Land.

This illustration provided by researchers depicts Kap Kobenhavn, Greenland, 2 million years ago, when the temperature was significantly warmer than northernmost Greenland today. (Beth Zaiken via AP) ((Beth Zaiken via AP))

Senior author Eske Willerslev, a geneticist at the University of Cambridge, said that millions of years ago the region was undergoing a period of intense climate change that sent temperatures rising and sediment likely built up for tens of thousands of years before the climate cooled and cemented the finds into permafrost – helping to preserve the DNA until the extraction process began in 2006.

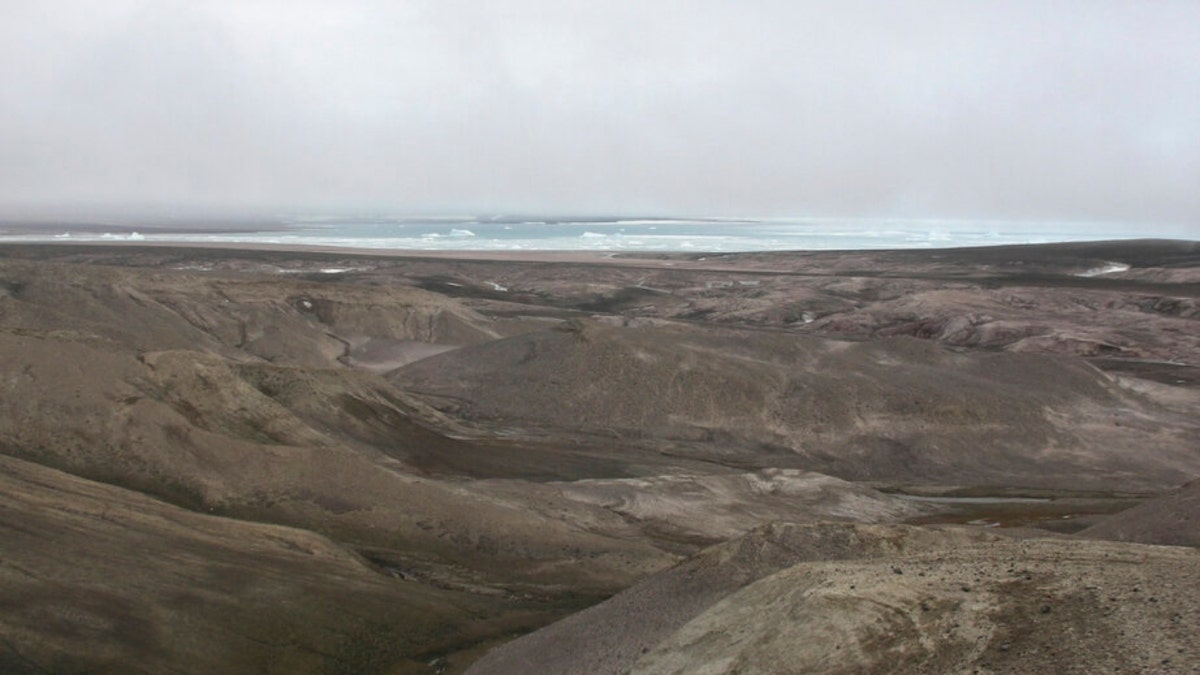

This 2006 photo provided by researchers shows geological formations at Kap Kobenhavn, Greenland. (Svend Funder via AP) ((Svend Funder via AP))

While the area is a barren Arctic desert today, back then the group found the landscape to have been lush, with Arctic plants and animals including the extinct mastodon.

"Of note, the detection of both Rangifer (reindeer and caribou) and Mammut (mastodon) forces a revision of earlier palaeoenvironmental reconstructions based on the site’s relatively impoverished faunal record, entailing both higher productivity and habitat diversity for much of the deposition period," the authors wrote.

This 2006 photo provided by researchers shows the landscape at Kap Kobenhavn, Greenland. The many hills have been formed by rivers running toward the coast. ((Kurt H. Kjaer via AP))

JONATHAN THE TORTOISE CELEBRATES 190TH BIRTHDAY, OLDEST LIVING LAND ANIMAL

During the warm period, average temperatures were 20 to 34 degrees higher than today.

A two million-year-old trunk from a larch tree is stuck in the permafrost within the coastal deposits at Kap Kobenhavn, Greenland. The tree was carried to the sea by the rivers that eroded the former forested landscape. ((Svend Funder via AP))

The DNA also showed traces of geese, hares, reindeer and lemmings, and the sediment built up in the mouth of a fjord suggested that horseshoe crabs and green algae lived in the area.

Although Laura Epp, an environmental DNA expert at Germany’s University of Konstanz who was not involved in the work noted that, based on the data, it’s hard to say for sure whether these species truly lived side by side.

Professors Eske Willerslev and Kurt H. Kjaer expose fresh layers for sampling of sediments at Kap Kobenhavn, Greenland. ((Svend Funder via AP))

Lead author Kurt Kjær, a geologist and glacier expert at the University of Copenhagen, said that means waters were likely much warmer back then.

Willerslev believes that because these plants and animals survived during a time of dramatic climate change, the DNA could offer a "genetic roadmap" to help the world adapt to current warming.

This 2006 photo provided by researchers shows a close-up of organic material in coastal deposits at Kap Kobenhavn, Greenland. The organic layers show traces of the rich plant flora and insect fauna that lived two million years ago. ((Svend Funder via AP))

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

He told Reuters that he would not be surprised to find DNA from at least 4 million years ago.

"Similar detailed flora and vertebrate DNA records may survive at other localities," the scientists said. "If recovered, these would advance our understanding of the variability of climate and biotic interactions during the warmer Early Pleistocene epochs across the High Arctic."

Reuters and The Associated Press contributed to this report.