Fox News Flash top headlines for Sept. 19

Fox News Flash top headlines for Sept. 19 are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com

There have been many theories about one of the biggest unsolved mysteries of anthropology -- what killed off Neanderthals -- but a new study puts a unique twist on the topic.

In a study posted online this week by the journal The Anatomical Record, a team of physical anthropologists and head and neck anatomists suggests that the culprit was not some bizarre pathogen, but instead a common childhood illness: chronic ear infections.

"It may sound far-fetched, but when we, for the first time, reconstructed the Eustachian tubes of Neanderthals, we discovered that they are remarkably similar to those of human infants," said co-investigator and Downstate Health Sciences University Associate Professor Samuel Márquez in a statement.

NORTH AMERICA'S BIRD POPULATION HAS DROPPED BY 3 BILLION SINCE 1970

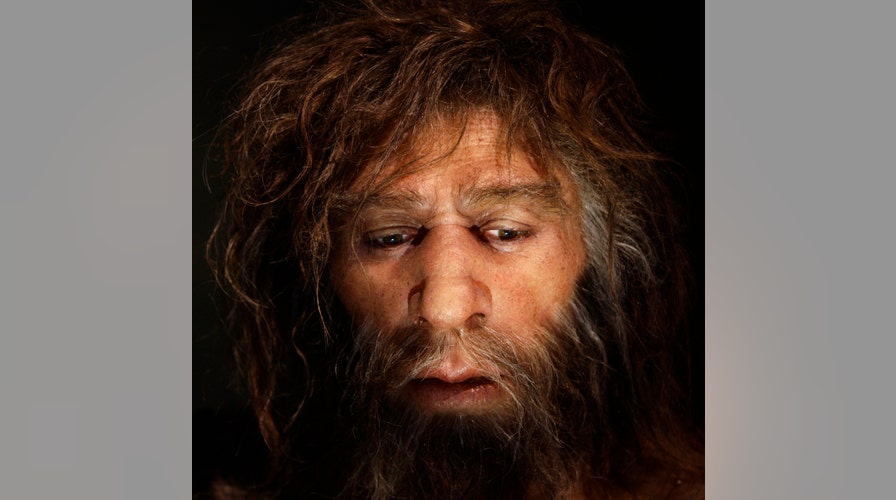

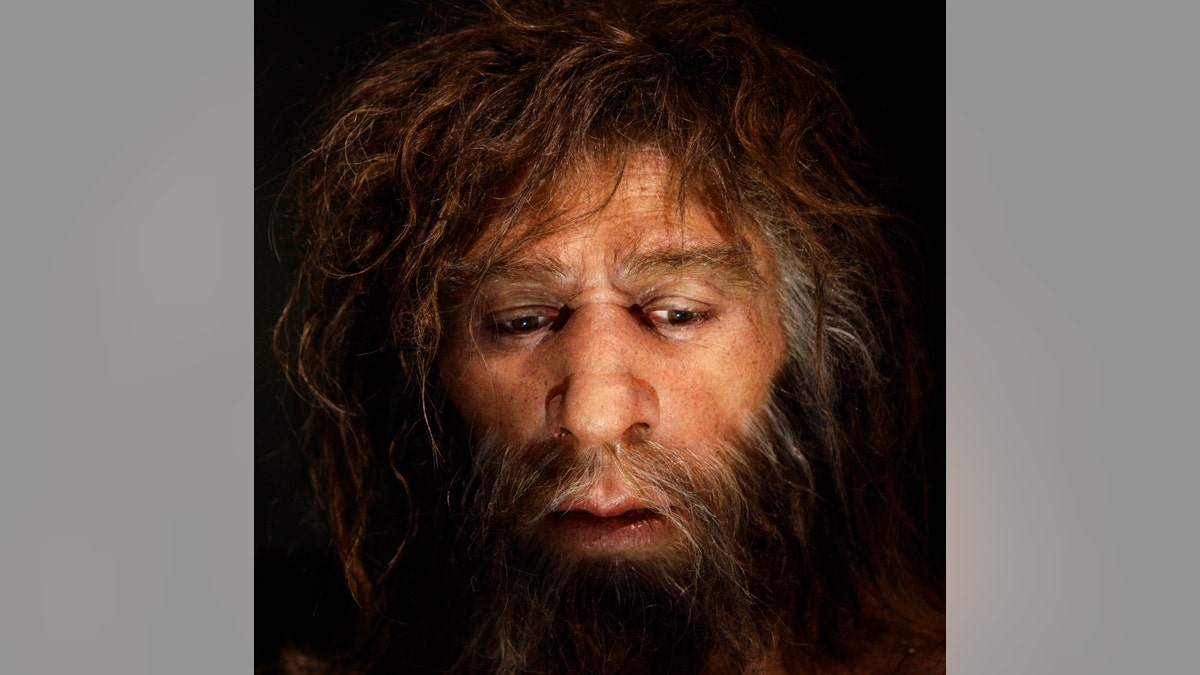

Hyperrealistic face of a Neanderthal male is displayed in a cave in the new Neanderthal Museum in the northern Croatian town of Krapina. (Reuters)

DID EGYPTIANS SPUR INNOVATION BY MYSTERIOUS BIBLICAL KINGDOM 3,000 YEARS AGO?

"Middle ear infections are nearly ubiquitous among infants because the flat angle of an infant's Eustachian tubes is prone to retain the otitis media bacteria that cause these infections - the same flat angle we found in Neanderthals."

Modern humans' Eustachian tubes, which connect the middle ear to the nasopharynx, would change as they age. With Neanderthals, they would not, meaning that the ear infections and potential complications, such as respiratory infections and pneumonia, would become chronic or lifelong threats.

"It's not just the threat of dying of an infection," said Márquez. "If you are constantly ill, you would not be as fit and effective in competing with your Homo sapien cousins for food and other resources. "In a world of survival of the fittest, it is no wonder that modern man, not Neanderthal, prevailed."