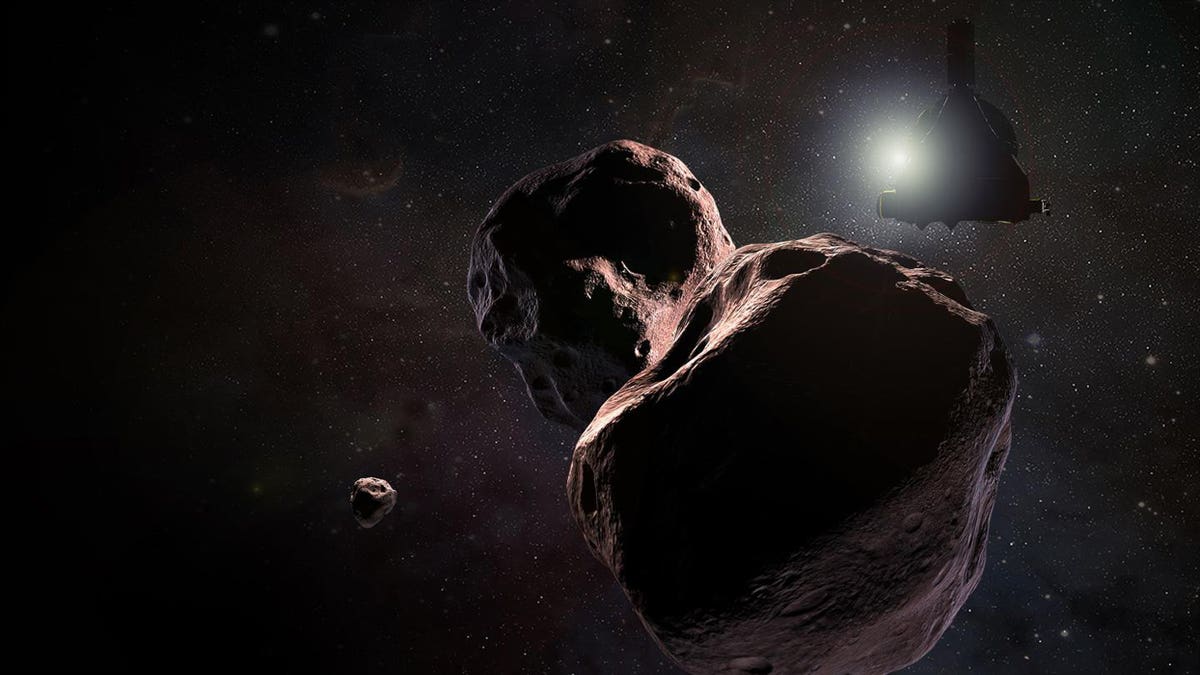

NASA's New Horizons spacecraft will make a close flyby of the Kuiper Belt object Ultima Thule, shown here in an artist's illustration, on Jan. 1, 2019. (NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/Steve Gribben) (NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/Steve Gribben)

As 2018 draws to a close and a new year dawns, one group of people plans to celebrate something far more unusual — a flyby of the most distant solar system object ever explored.

On Tues. Jan. 1, at 12:33 a.m. EST(0533 GMT), NASA's New Horizons spacecraft will fly by Ultima Thule, the tiny rock orbiting roughly 4 billion miles (6.5 billion kilometers) from the sun. Here's how to watch the flyby online today and tomorrow.

Even in the final days of the approach, however, Ultima Thule is playing things close to the vest. "We've never in the history of spaceflight gone to a target that we've known less about," Alan Stern, principal investigator of New Horizons and a researcher at the Southwest Research Center in Colorado, told reporters Sunday (Dec. 30). [Ultima Thule Flyby! Full Coverage]

But when the spacecraft arrives, it will turn a suite of instruments onto the mysterious object, and many of its mysteries will be unveiled. It's the second historic rendezvous for New Horizons, which zipped by Pluto in July 2015 on the first-ever flyby of that world.

"We are ready to science the heck out of Ultima Thule," Stern said.

Ringing in the New Year

Lying at the outskirts of the solar system, Pluto may seem alone at first glance. Only in the last few decades have scientists realized that it is one of a collection of objects that make up the Kuiper Belt, a band of rocky, icy objects that border the solar system. Smaller than planets, most of the inhabitants are left over from the formation of the solar system. They provide a glimpse of the early ingredients of the solar system, the bits and pieces that formed the larger worlds we know today. [NASA's New Horizons Mission in Pictures]

When New Horizons launched in 2006, no one knew anything about Ultima Thule. Scientists didn't discover the spacecraft's next target until 2014, about a year before the epic flyby of Pluto. Originally named 2014 MU69, Ultima Thule was one of three objects proposed for an extended mission target.

Since its 2015 selection as the next object for New Horizons to visit, researchers have scrambled to learn as much about Ultima Thule as possible. In 2017, they learned that the Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) was not spherical but seemed elongated, or possibly even made up of two orbiting bodies.

As New Horizons closed in on Ultima Thule over the last three months, it began snapping hundreds of photos of the object. But while the images revealed no sign of potential dangers that could harm the spacecraft, such asunexpected moons or clouds of debris that could slam into the spacecraft as it blew by the KBO, they also gave no hint about the shape of the body it is about to visit.

In fact, it's still possible that Ultima Thule is made up of not one but two objects, closely packed together. Stern told Space.com Saturday (Dec. 29) that the timeline for resolving whether the KBO is alone or part of a duet depends on how close the potential pair lie to one another.

"If they are touching, it will take until the last day," he said.

Stay on target

It's too late now to divert the spacecraft to a higher altitude, where it would be safe from any potential dangers. The last chance to make that decision passed on Dec. 13, and team member Will Grundy of Lowell Observatory in Arizona said that it takes months to come up with a new path.

At 9 a.m. EST on Sunday (Dec. 30), engineers sent the spacecraft its last command before the flyby, redirecting the closest image by two seconds, Bowman said. That readjusted the aim point for the flyby by about 19 miles (30 km). For comparison, Hersman said that during the Pluto encounter, the spacecraft was off by about 80 seconds. The team didn't find out until 9 p.m. EST last night (Sun. Dec 30) that the spacecraft successfully received the new commands. Had it not gone well, they would have immediately resent the same update.

New Horizons will fly only 2,200 miles (3,500 km) above the surface of the KBO, three times closer than it buzzed Pluto. To help conserve power, several components of the spacecraft will be temporarily turned off, according to Chris Hersman, Missions Systems Engineer at JHU APL. The student dust counter, which picks up roughly one micrometer-sized dust particle per day, and the transmitting portion of one of the radio transmitters. By turning off these tools, the spacecraft will be able to operate its scientific instruments.

In the hours leading up to the flyby, the spacecraft will be pointed at Ultima Thule, unable to communicate with Earth.

"We can't be in contact with the spacecraft and get data," said Alice Bowman, New Horizons' Mission Operation Manager.

When the clock strikes midnight in Maryland, most of the team won't be sitting in the control center at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU APL). They'll have migrated to the nearby Kossiakoff Education and Conference Center to ring in the new year.

Among them will be astrophysicist Brian May, a mission team member and former lead guitarist for the rock band Queen, who will play his new solo song, "New Horizons."

"We're all we're all huge fans," Bowman said.

The science team, at least, will likely remain at the center to celebrate the moment of the flyby half an hour later according to Cathy Olkin, New Horizons' Deputy Project Scientist. She wasn't sure about the operation team.

Immediately after the flyby, the spacecraft will turn back to Earth and send home an update on its status. The process that Bowman said will take about 15 minutes on Earth will take the spacecraft just over an hour as it has to change its orientation.

After phoning home, it will slew back to study a receding Ultima Thule retreating in the distance. The status update should arrive back on Earth at 10:30 a.m. EST (7:30 a.m. PST), Bowman said, and the first image should reach the ground around 2 p.m. (11 a.m. PST).

According to Stern, the first image will be rather rough, only about 6 pixels across. Not until the next day, Jan. 2, will the more detailed images arrive back on Earth to be released.

As it closes in on its destination, the spacecraft appears to be in good health. "Everything is looking great," Bowman said.

New Horizons Project Manager Helene Winters agrees. While Winters, who is based out of JHU APL, said that most of her fears have been set to rest by the images returned by the spacecraft, that doesn't mean the team is resting easy.

"We don't have any immediate concerns, but being engineers and scientists, we're always thinking about the what ifs," Winters told Space.com. "We want to make sure we mitigate all possible risks."

A pristine object

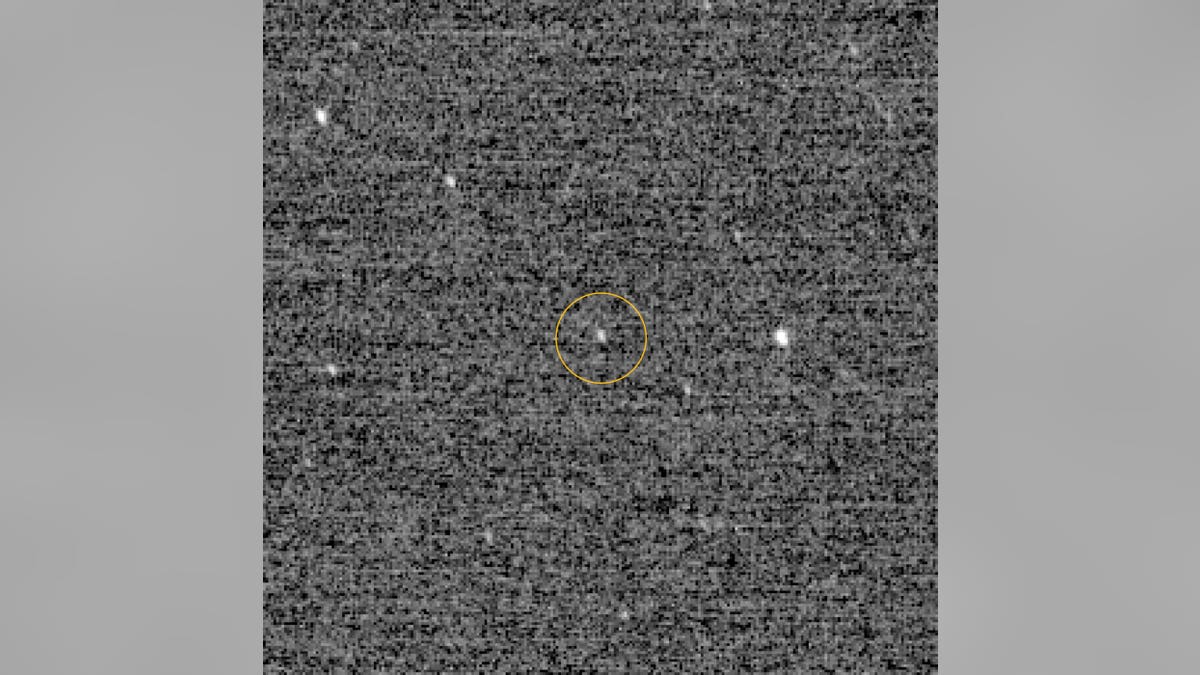

This is the first detection of Ultima Thule using the highest-resolution mode of the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager aboard the New Horizons spacecraft. Three separate images, each with an exposure time of 0.5 seconds, were combined to produce the image. (NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute) (NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute)

When the solar system formed 4.5 billion years ago, not all of the gas and dust surrounding the young sun became moons and planets. Some of the ancient debris remained in the form of KBOs and asteroids. But while asteroids are mostly rock, KBOs like Ultima Thule lie far enough from the sun that they held onto the bulk of their ice.

"Objects farther out than Pluto are untouched since the beginning of the solar system," Winters said. "The idea is that [Ultima Thule] looks like what things might have looked like at the beginning of the solar system."

Project scientist Hal Weaver, of Johns Hopkins University, is excited about visiting the KBO, which he said is "unlike anything else we've ever looked at with spacecraft." Only three days before the flyby, Ultima Thule remained a single pixel on the images returned by New Horizons. But as the spacecraft grew closer, grew several times larger each day. Weaver said that if Ultima Thule turned out to be 20 miles (32 km) across, it would cover about 200 pixels.

"Every single pixel is important," he said, stressing that the team planned to wring out every bit of science they could from the brief flyby.

What might the first pictures sent back of Ultima Thule look like?

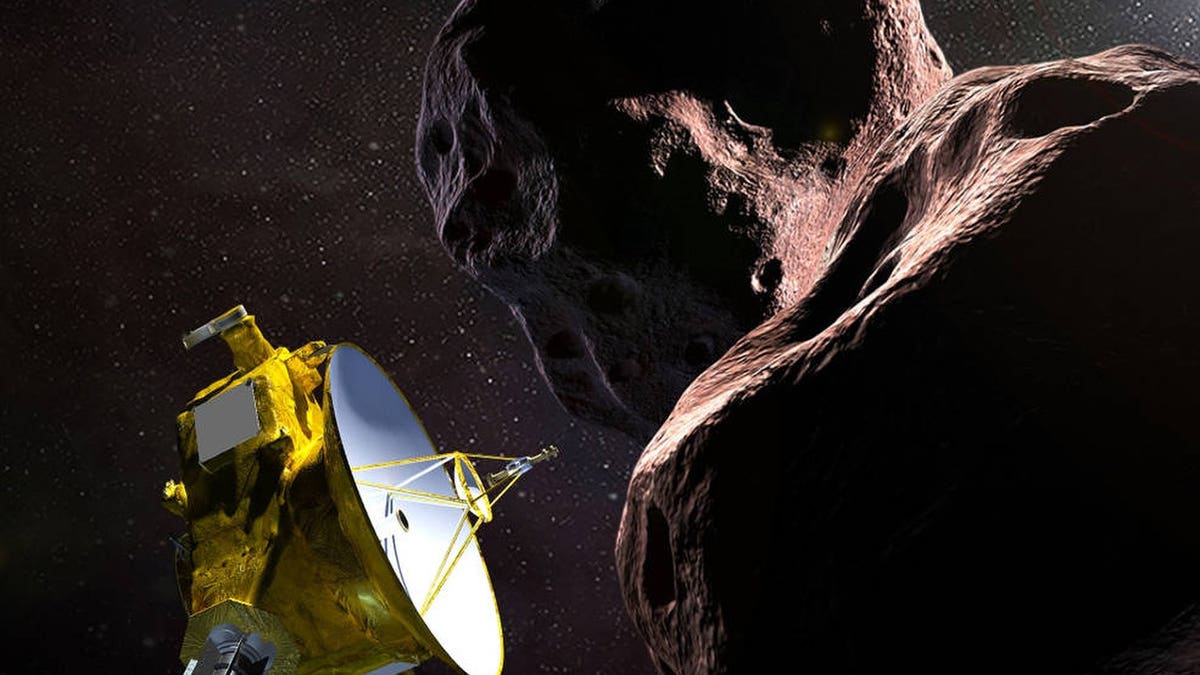

Weaver said the team anticipates an icy surface, probably covered with hydrocarbons. "We're almost positive there will be organic material covering the surface, dark reddish material."

Grundy, who is the leader of New Horizons' surface composition team, said that they don't expect a lot of surface activity today. However, it's possible that early in its life, Ultima Thule may have spewed ices and hydrocarbons, and there may be signs of that activity still present on the surface.

An artist's illustration of NASA's New Horizons spacecraft as it flies by Ultima Thule (2014 MU69) in the Kuiper Belt beyond Pluto on Jan. 1, 2019. (NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI)

How heavily cratered the KBO might be is also up for debate. To date, Pluto is the only other KBO that has been studied, and surface activity in its past covered many of its craters. But Grundy said the team doesn't anticipate a heavily pitted surface.

"We don't expect [Ultima Thule] to be very dense with craters, but we don't expect there to be none," he said.

Collisions with the KBO would have been slow, with speeds of less than 0.62 miles (1 km) per second. That may sound fast, but Grundy said its nothing compared to the several kilometers per second impacts that happen in the asteroid belt. In fact, KBO impacts may be more like dropping a shovel full of dirt on the ground—so slow that they don't even excavate a crater, Grundy said.

But a large crater could be quite revealing, slicing through the surface of Ultima Thule. If the KBO broke off from an even larger object, a massive impact crater could reveal layers of material that hint towards the target's origin. "That would be great," Grundy said.

It's even possible that Ultima Thule isn't a single large rock, instead a massive rubble pile drawn together by gravity.

"It probably is," Grundy said, pointing out that the bodies of the solar system were all born from pebble-sized objects. Ultima Thule "probably was born as a rubble pile," he said. Gravity drew the material close together, eventually forming a larger rock, but it's possible that Ultima Thule wasn't quite massive enough to make the merge. A collision could also break a solid object back into a pile of gravitationally bound gravel.

Whatever New Horizons reveals, it will definitely be something that has never been seen before.

"We anticipate there will be lots of faint results, even though Ultima Thule has been very stubborn about revealing its secrets," Weaver said.