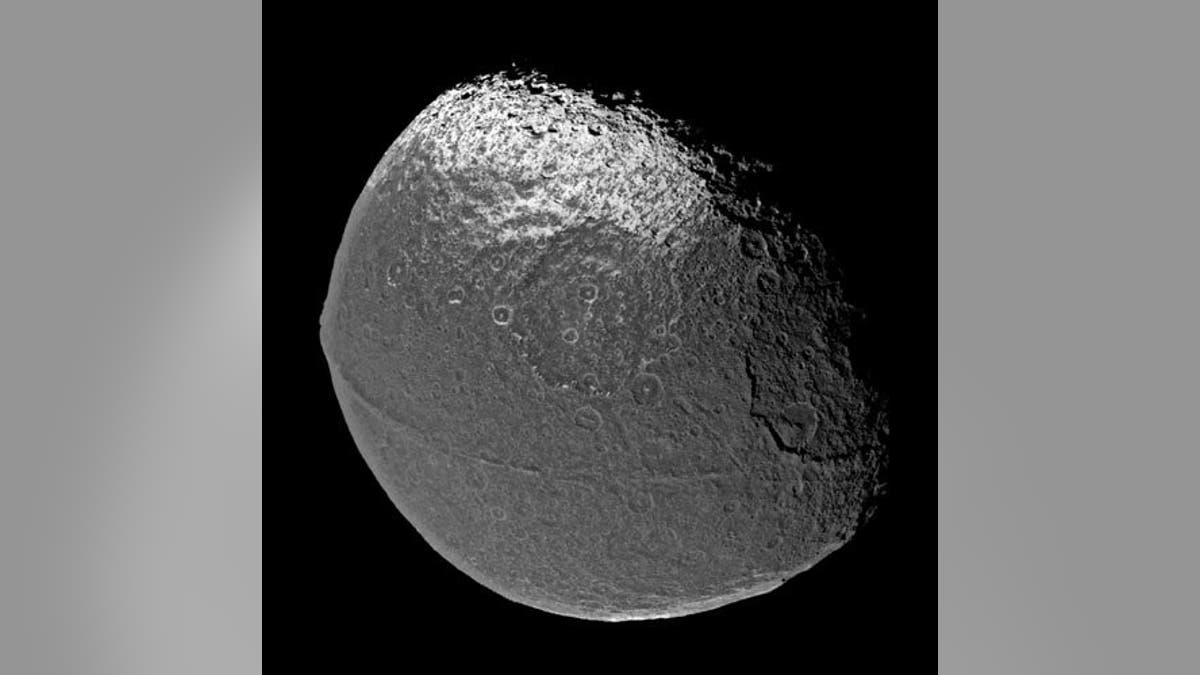

The giant ridge around the middle of Saturn moon's Iapetus that makes it resemble an oversize walnut may have essentially formed as a "hug" from a dead moon, researchers say.

Iapetus, the third-largest of Saturn's moons, possesses a mountain range like no other in the solar system. This enormous ridge wraps along its equator, reaching up to 12.4 miles (20 kilometers) high and 124 miles (200 km) wide, and encircles more than 75 percent of the moon. Altogether, the ridge may constitute about one-thousandth the mass of Iapetus.

"I would love to stand at the base of this wall of ice 20 kilometers tall that heads off straight in either direction until it dips below the horizon," study lead author Andrew Dombard, a planetary scientist at the University of Illinois at Chicago, told SPACE.com.

Scientists had been at a loss to explain how this mountain range might have formed. Of all the planets and moons in our solar system, apparently only Iapetus has this kind of ridge — any process that researchers previously suggested to explain its formation should also have led to similar features on other bodies. [Photos of Saturn's Moons]

Now investigators suggest this ridge could be the remains of a dead moon. Their model proposes that a giant impact blasted chunks of debris off Iapetus at the tail end of the planetary growth period more than 4.5 billion years ago. This rubble could have coalesced around Iapetus, making it a "sub-satellite," a moon of a moon.

Under this scenario, the gravitational pull Iapetus exerted on this sub-satellite eventually tore it back into pieces, forming an orbiting ring of debris around the moon. Matter from this debris ring then rained down, building the ridge Iapetus now sports along its equator fairly quickly, "probably on a scale of centuries," Dombard said.

The researchers suggest that, of all the planets and moons in our solar system, only Iapetus has this kind of ridge because of its unique orbit so far away from Saturn. This made it easier to have a moon of its own — if Iapetus was closer in, Saturn might have tugged Iapetus' moon away, Dombard said.

More elaborate computer simulations of this process, from the giant impact to the raining down of debris, are needed to test whether the model Dombard and his colleagues suggested might be how Iapetus' equatorial ridge formed. Such analyses would also help pin down specifics of the idea, such as how long it took the sub-satellite to tear apart. "My personal intuition suggests it took a half-billion to 1 billion years," Dombard said.

The scientists detailed their findings online March 7 in the Journal of Geophysical Research-Planets.