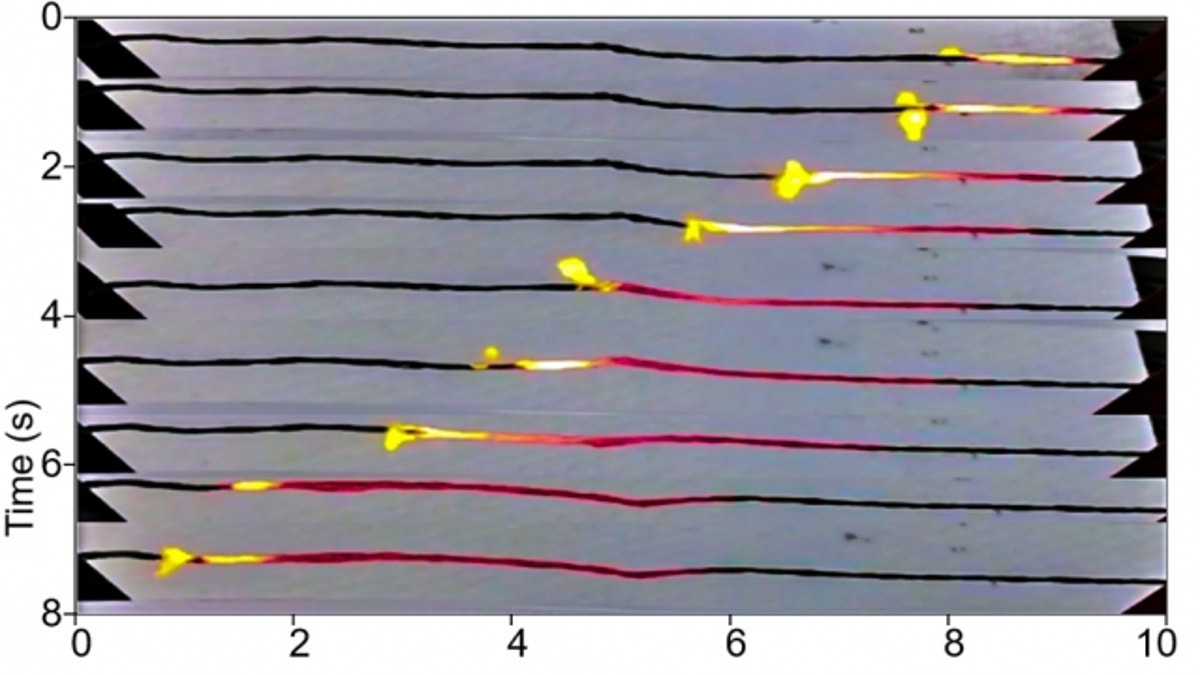

In this time-lapse series of photos, progressing from top to bottom, a coating of sucrose (ordinary sugar) over a wire made of carbon nanotubes is lit at the left end, and burns from one end to the other. As it heats the wire, it drives a wave of electrons along with it, thus converting the heat into electricity. (Michael Strano)

A team of researchers at MIT have come up with an environmentally friendly way to generate electricity that harnesses heat but uses no metals or toxic materials.

The breakthrough is critical because most of the batteries that power everything from smartphones to computers are made of toxic materials like lithium, which can be difficult to dispose of and have a limited global supply. Lithium is alslo extremely flammable.

The breakthrough is based on a 2010 discovery by MIT’s Michael Strano, who found that a wire made from tiny cylinders of carbon known as carbon nanotubes can produce an electrical current when it is progressively heated from one end to the other – much as you would light a fuse.

Related: Stanford researchers unveil technology that could prevent battery fires

The effect arises as a pulse of heat pushes electrons through the bundle of carbon nanotubes, carrying the electrons with it like surfers riding a wave.

Now, Strano and his team including grad students Sayalee Mahajan and Albert Liu have gone a step further, increasing the efficiency of this technique more than a thousandfold. In other words, they have produced devices that can put out power similar to what can be produced by today’s best batteries.

Their work was published in the journal Energy & Environmental Science.

The improvements in efficiency, Strano said in a statement, brings the technology “from a laboratory curiosity to being within striking distance of other portable energy technologies,” such as lithium-ion batteries or fuel cells.

Already, the device is powerful enough to show that it can power simple electronic devices such as an LED light. And unlike batteries that can gradually lose power if they are stored for long periods, the new system should have a virtually indefinite shelf life, Liu said. That could make it suitable for uses such as a deep-space probe that remains dormant for many years as it travels to a distant planet and then needs a quick burst of power to send back data when it reaches its destination.

Related: Tesla touts new battery technology, wants to change US power usage

In addition, the researchers said the new system is very scalable for use in the increasingly tiny wearable devices. In contrast, batteries and fuel cells have limitations that make it difficult to shrink them to tiny sizes, Mahajan says, whereas this system “can scale down to very small limits. The scale of this is unique."

Kourosh Kalantar-Zadeh, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at RMIT University in Australia who was not involved in this research, said in a statement that this work is “an important demonstration of increasing the energy and lifetime of thermopower wave-based systems.”

“I believe that we are still far from the upper limit that the thermopower wave devices can potentially reach,” he said. “However, this step makes the technology more attractive for real applications."

Still, the MIT researchers cautioned that it could take several years before the process could be available commercially.