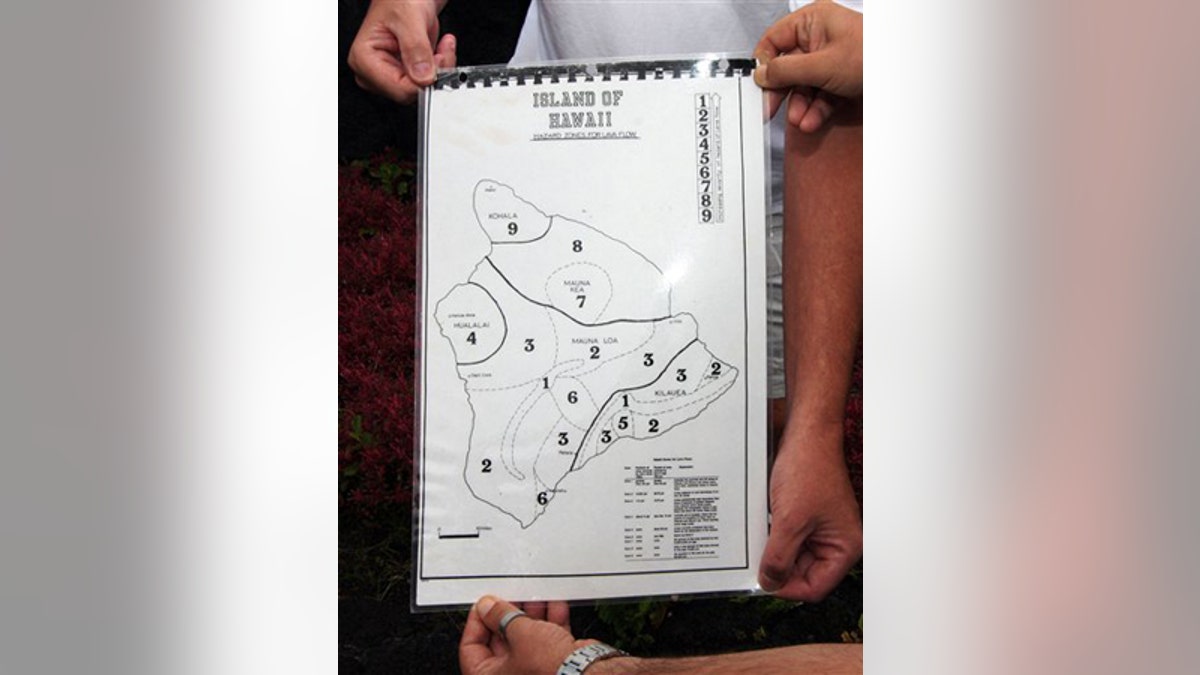

In this photo taken Aug. 25, 2009, a map showing hazard zones for lava flow is seen in Pahoa, Hawaii. Insurer, Liberty Mutual Fire Insurance Co., no longer covers property located in Lava Zone 1, an area of the Big Island with the highest risk of inundation from Kilauea. The volcano has been erupting since Jan. 3, 1983. (AP Photo/Tim Wright)

PAHOA, Hawaii – The U.S. Geological Survey's 35-year-old maps of lava danger zones in this southern corner of the Big Island are a tableau of earthy colors and odd shapes originally meant for scientific and planning purposes.

The maps have also long been used by the home insurance industry to assess lava hazard risks. But in the last year or two, the maps have become a source of contention as insurers have hiked rates or completely abandoned areas around this small town that are deemed to be the most dangerous.

And Fannie Mae, the huge backer of home mortgages, recently declared it would no longer do so in the two most hazardous zones. That has residents pointing fingers of blame at the charts that even the Geological Survey acknowledges are outdated and need to be replaced.

"Now that it has become the bible, so to speak, there's no way to get rid of it," local real estate agent John Dirgo said of the maps. "It's being used for purposes it was never intended for."

Wendy Ford's home is located in the zone deemed most at risk, and until this year, she's paid less than $425 a year for insurance. But her premiums are skyrocketing now even though her neighborhood hasn't seen new lava since 1790.

"I just keep looking and looking at these maps and (they don't) make any sense," she said.

But for insurance companies, which essentially have to predict the future when assessing risk, the maps are a valuable tool when deciding to offer coverage in a given area and how much it will cost, said state Insurance Commissioner J.P. Schmidt.

The maps "provide an objective, scientific standard that they can use to help determine the risk that they are facing," he said.

The Geological Survey last revised the lava hazard maps for the entire Big Island and the Puna district in 1987. The 500-square-mile district encompasses Kilauea, one of the world's most active volcanoes that has oozed lava since 1983.

The agency produces similar maps in Washington, Oregon and Alaska, but volcanoes there are located farther from populated areas and are not as active as the Big Island's.

The map of the Puna district shows the five most dangerous zones. The highest risk is in Zone 1, a narrow band extending the district's length where vulcanologists say lava can appear in any spot with little warning. More than 25 percent of the land there has been covered with lava since 1800. In the somewhat less dangerous Zone 2, lava has covered 15 to 25 percent of the land since 1800; no lava has flowed since 1800 in Zones 5 through 9.

Ford's two-acre property is in the Leilani Estates subdivision, a 45-year-old tract where homes are separated by vibrantly green foliage dotted with old-growth ohia trees. It sits more than 10 miles from the the closest active lava flow, yet, it's in Zone 1. The land underneath a nearby development, Nanawale Estates, was inundated in 1840 but is in Zone 2, as is the town of Pahoa.

Liberty Mutual insured Ford's 2,200-square foot, three-bedroom home that was assessed at $231,000 for $424 last year. The company had wanted to cancel her policy last year after it decided to no longer cover homes in zones 1 and 2, but relented for one year after Ford complained to state regulators.

But the coverage has now lapsed, and Ford's separate hurricane policy also jumped much higher.

That left her stuck with only two choices: Lloyd's of London or the state-created Hawaii Property Insurance Association. Both quoted her rates of more than $3,000 annually. She eventually chose Lloyds, which includes hurricane coverage, at $3,147 a year.

The 17-year-old HPIA, the insurer of last resort for Hawaii homeowners, covers 2,400 properties on the Big Island. It has hiked rates almost 60 percent in the last two years because of higher coverage limits and reinsurance costs, said Schmidt, the state insurance commissioner.

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina and other natural catastrophes in the United States cost insurers $62 billion, several times the annual average of $10 to $12 billion, said Robert Hartwig, president of the Insurance Information Institute. Last year's $26 billion in payouts was the third highest ever.

With such losses, Hartwig added, the rising cost of providing coverage in disaster-prone areas has prodded some insurers to reduce their exposure.

Still, there has been no swell of complaints about policy cancellations from Zone 1 residents to local insurance agents, public officials or Schmidt's agency.

Liberty Mutual would not elaborate on its use of the maps, but did say in a statement, "Specifically, we have determined that properties within Lava Zones 1 and 2 pose too great an underwriting risk because of their susceptibility to lava-related damages."

Schmidt said the industry probably noticed two lava flows in the last 20 years: One in 1990 that overran the town of Kalapana and another two years ago that headed for but stopped far short of residential developments between Pahoa and Hilo.

"I'm sure that they looked at ...the possible projected path," he said, "and the homes that they had insured in the area."

Moreover, some companies without local agents didn't realize they had approved policies in areas considered hazardous, and left when they found out, said Phil Rellinger, president of Triad Insurance in Honolulu.

The companies "find out about it and say, 'Oops, what are we doing there?"' Rellinger said.

Fannie Mae also has blacklisted zones 1 and 2. In June, it abruptly announced it would no longer buy or securitize mortgages there, citing the increased risk of property destruction.

A spokeswoman would not elaborate on the quasi-government agency's action.

Still, most everyone agrees that more precise maps would help the situation.

The Geological Survey has long worked on ways of estimating when lava might appear in any one place and then drawing maps from that, much like flood zone maps, said Jim Kauahikaua, scientist-in-charge at the agency's Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. But the new cartography is years away, he said.

Still, history has shown that Kilauea's lava can spout anywhere, anytime in the most dangerous zones — even in Ford's lush backyard, said Frank Trusdell, a geologist with the volcano observatory.

"The frequency of eruptions says that within her lifetime it's highly likely there's going to be an eruption close by that will definitely impact her," he said.