Fox News Flash top headlines for March 17

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

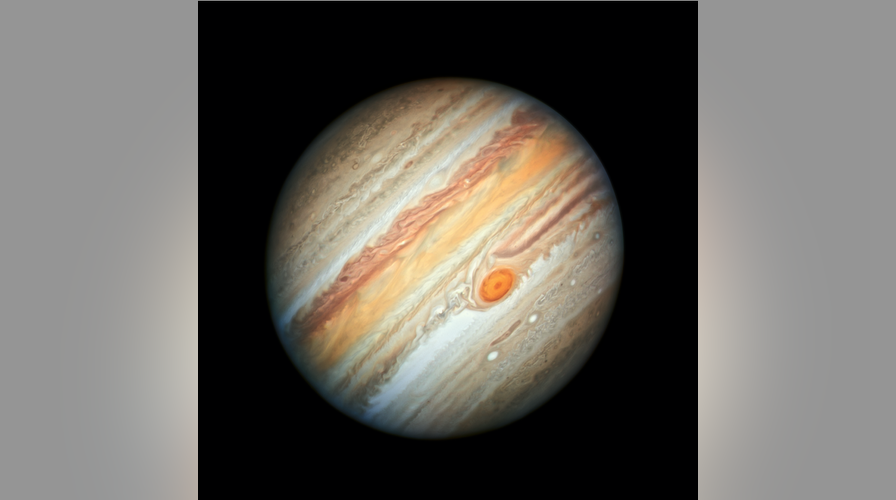

Jupiter's Great Red Spot (GRS) has fascinated researchers for nearly 200 years, having been continuously observed since 1830. A new study suggests that the clouds are shrinking, but not in ways researchers might expect.

The study, published in Nature Physics, suggests that the storm is still as thick as it was 40 years ago, when NASA's Voyager flew past it in 1979.

"For the Great Red Spot in particular, our predicted horizontal dimensions agree well with measurements at the cloud level since the Voyager mission in 1979," the researchers wrote in the study. "We also predict the Great Red Spot’s thickness, which is inaccessible to direct observation. It has remained surprisingly constant despite the observed horizontal shrinking."

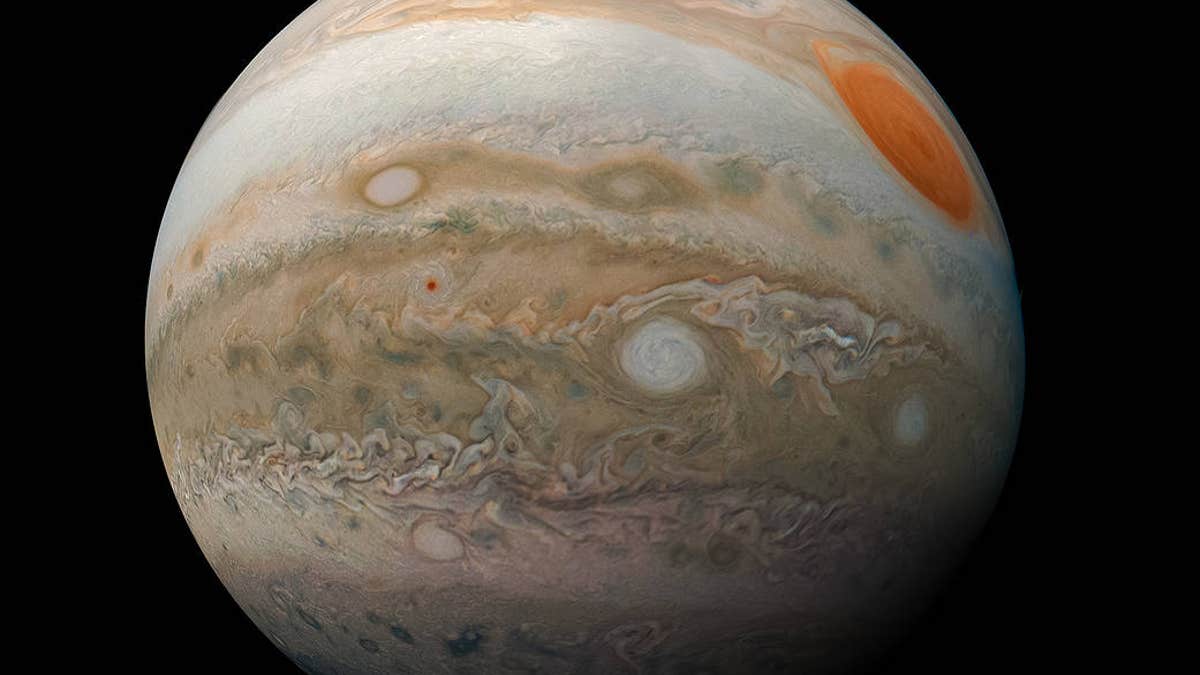

The image shows Jupiter's Great Red Spot and storms in the gas giant's southern hemisphere. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS/Kevin M. Gill)

JUPITER'S GREAT RED SPOT WON'T DIE ANYTIME SOON, RESEARCHER SAYS

The researchers used numerical simulations and performed experiments with salt-water in a Plexiglas tank to make their observations.

"We determine the generic force balance responsible for their three-dimensional pancake-like shape," the researchers added. "From this, we define scaling laws for their horizontal and vertical aspect ratios as a function of the ambient rotation, stratification and zonal wind velocity."

There has been some controversy in the scientific community over whether Jupiter's Great Red Spot is actually shrinking, with recent reports suggesting the clouds are getting smaller.

The new study, which estimated the GRS is approximately 105 miles thick, will await NASA's Juno observations to further observe how thick the storm is and continue to learn about the planet's formation and history.

JUPITER COLLIDED WITH STILL-FORMING PLANET 4.5B YEARS AGO: 'ONE IN A TRILLION PROBABILITY'

NASA's Juno probe has been orbiting the celestial giant since 2016 and passes over both of the planet's polar regions every 53 days.

Jupiter continues to be a source of fascination for astronomers. In August 2019, a study suggested it may have had a massive collision with a "still-forming planet" approximately 4.5 billion years ago.

Two of Jupiter's 79 known moons, Europa and Io, are also a source of intense interest for researchers. In August 2019, NASA said it would explore Europa, an icy celestial body that could be habitable for humans and support life, as soon as 2023.

In November 2019, an international research team detected water vapor above the surface of Jupiter’s moon Europa for the first time. It's unclear what the oceans on Europa are made up of, but the Hubble Space Telescope detected the presence of sodium chloride on its surface, according to a study published in June.

NASA MISSION TO EUROPA COULD 'POSSIBLY SENSE LIFE'

The conditions on Europa have been previously likened to exoplanet Barnard B, a "super-Earth" 30 trillion miles from Earth. It likely has a surface temperature of roughly 238 degrees below zero and may have oceans underneath its icy surface, according to a July 2018 statement from NASA.

NASA is launching a mission to Europa within the next decade, a trek that could answer whether the icy celestial body could be habitable for humans and support life.